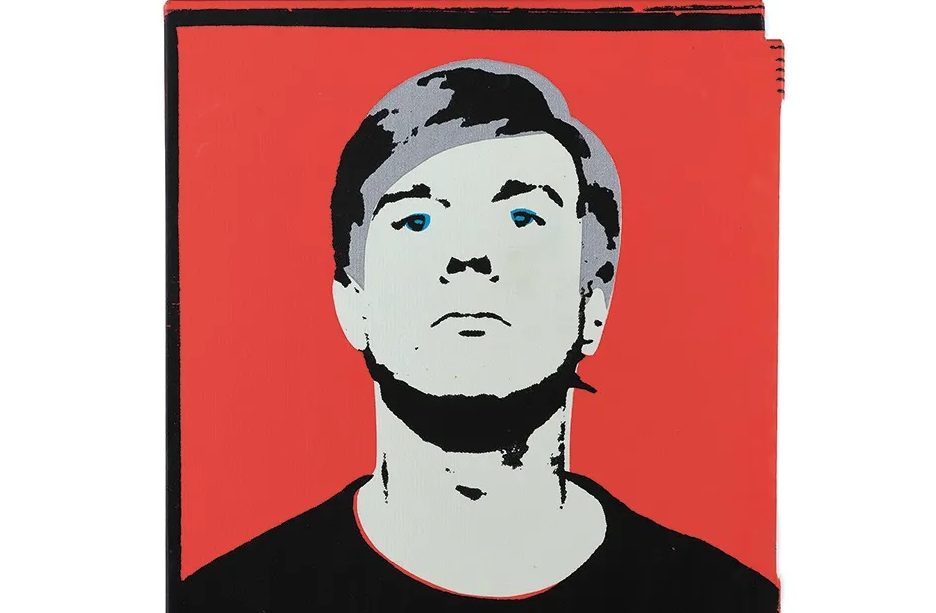

‘If you want to know all about Andy Warhol,’ the artist said in the East Village Other in 1966, ‘just look at the surface: of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.’

This quotation re-appeared in 2002 on the US Post Office’s commemorative Warhol stamp. It’s fabulously fitting for a stamp that reproduced a self-portrait, but when scholars recently compared the audiotapes of the interview with the printed version, the passage wasn’t on the tapes. Warhol sometimes invented interviews from whole cloth. He answered questions with a gnomic ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or, refusing to speak at all, allowed proxies like his ‘superstar’ Edie Sedgwick to answer for him. After all, he was just surface — leather jacket, shades, wig. The magus of mass production was there and everywhere forever, but nowhere in particular.

This negation of personality seems a publicity ploy, or the evasiveness of a shy man, or possibly the self-protection of a gay man in pre-Stonewall America. It was all of this, but also much more. The self-as-surface routine was perfect for a new kind of celebrity, one founded less on accomplishment and talent and more on presenting a surface for the projected desires of a mass audience. Authenticity and the sense of a deep self were obstacles to the creation of this new celebrity persona. Warhol made millions by autographing screen prints that were mass-produced by anonymous assistants.

Warhol somehow understood how this all worked. Born in 1928 in Pittsburgh to working-class Catholics from eastern Europe who barely spoke English, he realized the power and danger of being known to the world. The flipside of ‘15 minutes of fame’, Warhol suggests again and again, is death. The paintings of Marilyn Monroe memorialized her suicide; those of Jackie Kennedy, her suffering following her husband’s assassination. After Warhol survived his own assassination attempt in 1968, he allowed Richard Avedon to photograph the surgeon’s scars that crisscrossed the surface of his torso.

There is no narrative development or personal bildungsroman in Warhol’s art, and his affectless manner resists psychologizing, the biographer’s stock-in-trade. His images are impressions, flashes whose immediacy, flatness and repetition carry little sense of progression. The Brillo box contains no story, and the subject of a film like Empire, with its eight hours of static footage of the Empire State Building, remains inanimate.

Despite Warhol’s resistance, Blake Gopnik has written an extraordinary and revealing biography — surely the definitive life of a definitive artist. He accomplishes this through broad and deep, even obsessive, research into what he calls Warhol’s ‘social network’. Gopnik reports that he consulted 100,000 period documents and interviewed 260 of Warhol’s lovers, friends, colleagues and acquaintances. Warhol kept everything — he was a hoarder, collector and archivist all his life — and Gopnik has left no archival folder unopened or box unperused. Across 976 pages and more than 7,000 footnotes on a separate website, he recreates the swirl of ideas, culture and especially people that orbited Warhol.

Warhol famously thought of his studio as a factory, producing work after work off an assembly line. The catalogue raisonné of his paintings, drawings, films, prints, published texts and conceptual works would, if it were ever completed, rival that of the other master of 20th-century self-replication, Picasso. Gopnik has surveyed it all.

There is something interesting, revealing or humorous on just about every page. Gopnik deftly excavates his data mine. His prose is precise and pointed, and his year-by-year narrative clips along. He is also a master of pithy and informative character and historical sketches:

‘Warhol’s Pop wasn’t about borrowing a detail or two from commercial work, as many of his closest colleagues [like Robert Rauschenberg] did; it was about pulling all its most dubious qualities into the realm of fine art and reveling in the confusion they caused there. ‘He wants to make something that we could take from the Guggenheim Museum and put it in the window of the A&P over here and have an advertisement instead of a painting,’ complained one early critic of Warhol’s, getting it right, but backward: Pop pictures started in the windows and then migrated to the museums.’

Warhol is about the Age of Warhol as much as Warhol himself. We learn about the new possibilities of gay life in 1950s New York, the city’s underground film scene, the history of silk-screening (so important to Warhol’s art), the fluctuations of the art market, the history of department-store window design. We learn about fascinating things we may not even want to learn about, such as the size and color of Warhol’s penis. (Large and gray, like the Empire State Building.)

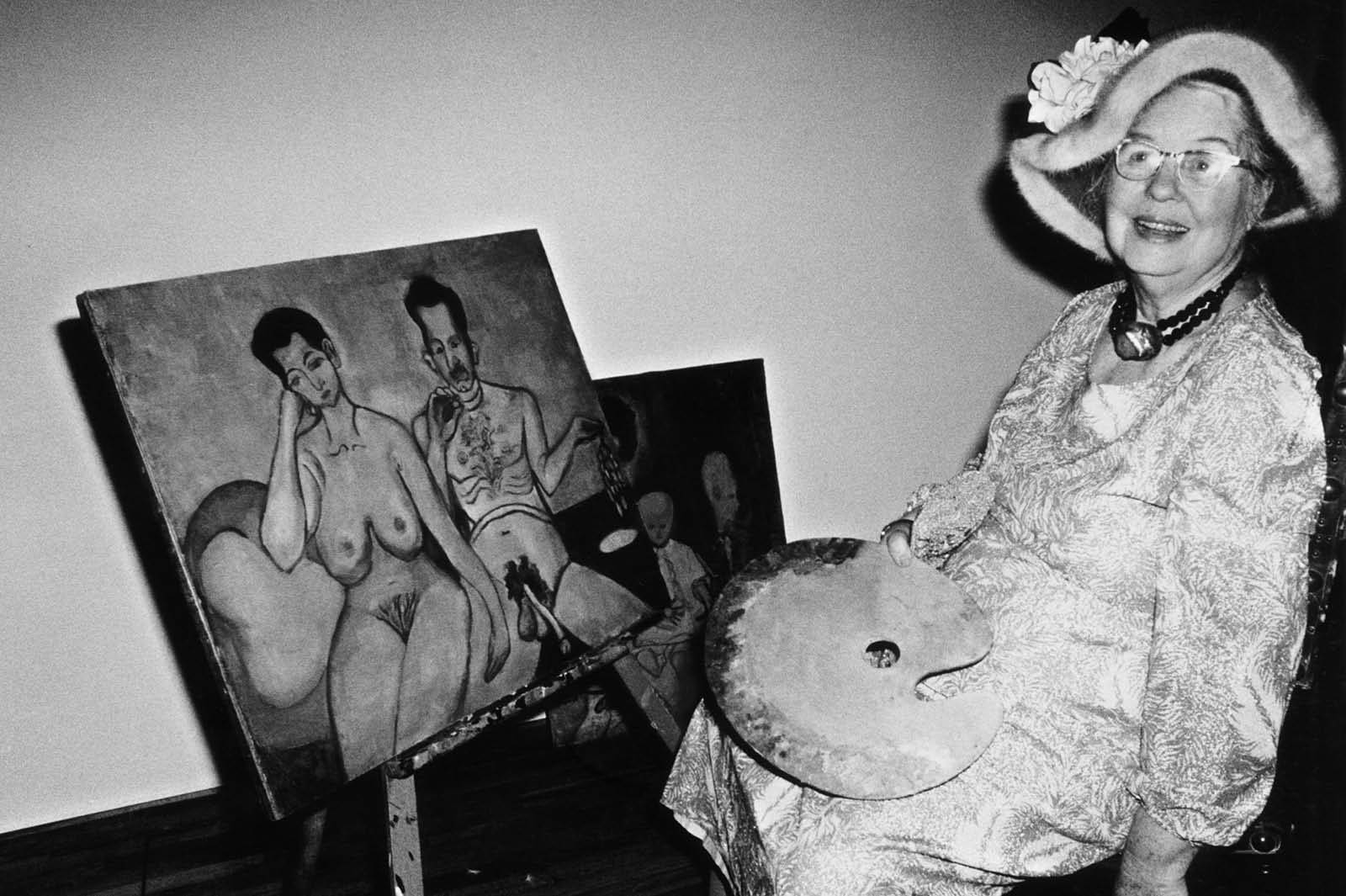

Warhol arrived in New York City in 1949 and quickly made a name for himself as a commercial illustrator, especially of women’s shoes. He lived for two decades with his mother, Julia, one of his most influential muses, and sought out an emerging coterie of gay artists including Truman Capote, with whom he had a stalkerish infatuation. The great Pop paintings of the early 1960s transformed American art. No less important was Warhol’s mid-Sixties salon and studio, the Silver Factory (silver because wallpapered in aluminum foil). This perverse and fecund anti-commune of ‘superstars’ and hangers-on spawned Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground, as well as Warhol’s wannabe assassin, Valerie Solanas. On June 3, 1968, Solanas shot Warhol in the name of feminist revolution. His heart ceased beating on the emergency room table before a determined surgeon saved him. In the 1970s, he turned to what he called ‘business art’, mainly portraits of other famous people. He died in 1987, aged 58, after gallbladder surgery.

Gopnik unpicks many of the conventions of Warhol’s non-biography. Warhol wasn’t an aesthetic rube when he arrived in New York. He had received an extraordinary avant-garde education from four years at the Carnegie Tech art school and at the Outlines gallery, which had brought Jackson Pollock, Alexander Calder, Joseph Cornell, Francis Bacon, Merce Cunningham and many other transformative artists to Pittsburgh in the 1940s. Warhol did not suddenly reinvent himself as a Pop artist in the early 1960s. As he built a successful career illustrating advertisements in the Fifties, he regularly tried to cross the line between commercial and fine art — a crossover he finally achieved in late 1961 with ‘Campbell’s Soup Cans’.

Warhol was baptized ‘Drella’ by acquaintances — part bloodsucking Dracula and part innocent yet social-climbing Cinderella. But Gopnik also argues that one of Andy’s greatest desires was for compassionate companionship. This was never achieved. The ‘routine’ gallbladder surgery which led to his death was anything but routine. He had been very ill for weeks but avoided treatment out of a lifelong fear of surgery and a misplaced faith in the healing powers of crystals.

Emphasizing Warhol’s radical ambiguity in art and life, Gopnik makes it impossible to say anything easy about him. His Warhol is a complex artist practicing what Gopnik, in a marvelous turn of phrase, calls ‘superficial superficiality’. The Warhol brand, the images of branded goods, famous faces and dollar bills, celebrates consumerism but also leaves us a little nauseated from our commodity fetishism. Warhol’s endless ‘boring’ films are hard to ignore because they give us so much space and time to think. They are studies in modern emptiness, and thus deep meditation. Warhol the critic of modern celebrity was also one of its greatest adulators.

This double image of Warhol seems just right. ‘His true art form,’ Gopnik writes, ‘first perfected in the first days of Pop, was the state of uncertainty he imposed on both his art and his life: you could never say what was true or false, serious or mocking, critique or celebration… Examining Warhol’s life leaves you in precisely the same state of indecision as his Campbell’s Soup paintings do.’

Gopnik’s analysis of Warhol’s ambivalence evokes another great observer of midcentury American culture. Lionel Trilling, the gray-suited lion of Columbia’s literary studies, would have hated Warhol, had he deemed the Silver Factory worthy of a visit. Still, Trilling’s America is Warhol’s:

‘A culture is not a flow, nor even a confluence; the form of its existence is struggle, or at least debate — it is nothing if not a dialectic. And in any culture there are likely to be certain artists who contain a large part of the dialectic within themselves, their meaning and power lying in their contradictions.’

To Trilling, the great American authors contained ‘both the yes and the no of their culture, and by that token they were prophetic of the future’. Warhol absorbed and reflected the affirmations and negations of his America — but was he prophetic of ours?

Yes and no. For a long time now we have lived in the Age of Warhol. If he were alive today, he would film us staring blankly at the social networks on our smartphones, hour after hour, while nothing and everything go on and on. By retaining ambivalence, Warhol allowed us to recognize and experience the deepest ethical dilemmas of American life — and he paid a price for being our screen and mirror.