Andy Warhol’s legacy has been dogged by rows over authenticity more than that of any other modern artist. Warhol might well have predicted the chaos and even delighted in it. He once signed a fake painting at Christie’s — four silkscreened Jackie Kennedys — for the hell of it. “I don’t know why I ever did,” he wrote in his diary — and yet the confession makes clear that he maintained a distinction, in the end, between what was fraudulent and what was his. You can’t sign a fake if everything is real.

The task of the Andy Warhol Authentication Board — established in 1995 by the foundation which handles the artist’s vast legacy — was to uphold that distinction, preserving the integrity of his corpus. But by the time of its dissolution in 2012, the committee of supposed experts had become shrouded in the very kind of murk it was set up to dispel. Stories circulated of questionable attributions, including a group of forty-four “fake” Warhols reassessed as genuine and of major paintings dismissed as fakes.

Warhol had so much work that even Agusto, the security man, was doing the painting

The queasy pleasure of Richard Dorment’s Warhol After Warhol is in learning just how much ineptitude can lie behind a bureaucratic façade. Twisting and tightly paced, the story centers on a charismatic (if highly obsessive) American collector, Joe Simon, who submitted two works to the board in 2002, only to have them stamped DENIED in indelible ink — rendered valueless. Simon was advised by Vincent Fremont, the salesman for the Andy Warhol Foundation, not to sue: “Don’t even think about it. They’ll drag you through the courts until you bleed — they never lose.”

The words were prophetic, but Simon’s — and Dorment’s — story is bigger than that of a legal wrangle, and more fascinating. In lucid prose, Dorment distils ideas that have dominated art theory for decades — those of authorship, reproduction and originality. Through the particulars of Simon’s case, he traces the changing techniques of Warhol’s various silkscreen series — from the Marilyns to the Maos; from the serial electric chairs to the gleefully banal society portraits of the 1970s and 1980s. And he draws on the testimony of people who worked at Warhol’s studio, the Factory, as it evolved from a drug-hazed, silver-sprayed hangout — peopled by a mixture of “uptown social types… speed freaks and hustlers, drug fiends and drag queens” — to a corporate operation in which the artist was forced to work on the floor of the lobby, hemmed in by offices.

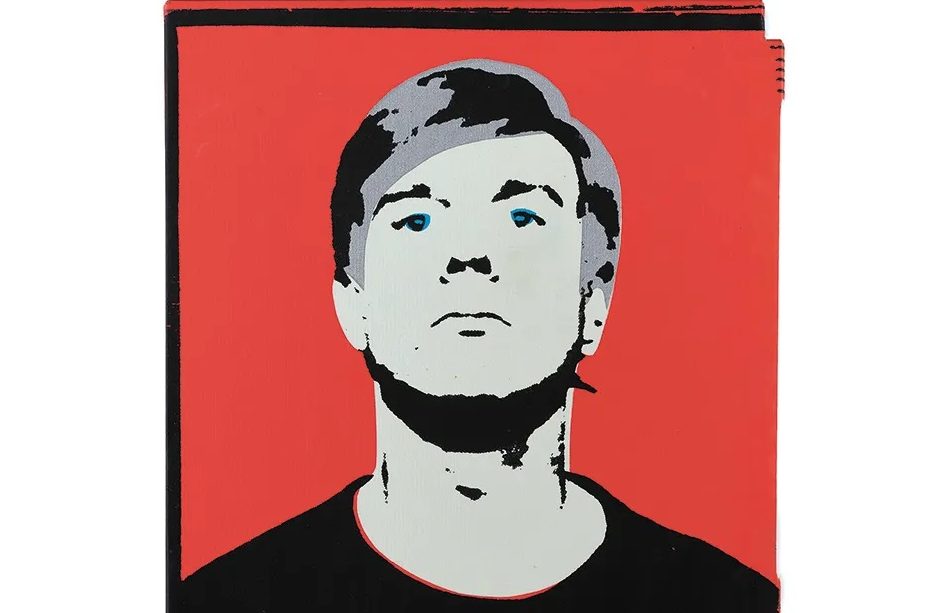

If only, one comes to realize, the members of the authentication board had been half as meticulous. The first of Simon’s contested works, a dollar-bill collage, proved after all to be a replica — although the board’s refusal to share its evidence, and its continued invitations to Simon to resubmit the piece, bordered on the sadistic. “Red Self-Portrait” was another matter. The silkscreened painting belonged to a series of eleven that Warhol allowed the magazine publisher Richard Ekstract to print at his own expense in 1965. Although Ekstract was paying production costs, it was an exchange of art for services: Warhol wanted to keep hold of a “video recording machine,” the loan of which Ekstract — who had connections with Phillips Electronics — had facilitated.

For Warhol, it was an act of authorial displacement worthy of Duchamp, or, as Dorment suggests, “like taking his hands off the wheel to see where the car would end up.” It was expedient, too: “In the words of a printer who worked closely with Warhol but wishes to remain anonymous, ‘he was cheap and lazy.’” From the 1970s, “Art by Telephone” was his default mode — he had made an art form of delegation. His chief printer at the time recalled: “He had so much work that even Agusto [the security man] was doing the painting.”

The portraits printed by Ekstract were less “authentic” in appearance than a series which Warhol had made using the same acetates (akin to stencils) the previous year. The tonal contrasts were fewer, the finish smoother. But the fact that Warhol considered the works his was attested by the fact that he signed one for his long-term dealer Bruno Bischofberger (a sincere testament, as opposed to his whim at Christie’s), and allowed the same work to serve as the cover image for the first catalogue raisonné of his art. This and other evidence did nothing to change the board’s mind. In 2006, “Red Self-Portrait” was denied for the second time.

As the story intensifies, even with the awareness that it is written from an angle, the wilful opacity of the board baffles and infuriates. The reader experiences a modicum of the blazing sense of injustice that has plagued Simon for twenty years. The tale could easily have been arcane and legalistic in the telling, but Dorment disentangles the thicket of names, emails, off-the-cuff remarks, snatches of gossip and deposition transcripts with mastery.

Sleuth-like in its plotting and with chapter headings which sometimes recall those of a Victorian thriller (“A Cold-Blooded Murder,” “A Brazen Swindle”), Dorment’s book is at heart a morality tale, a story of egos, hubris and folly. He can be damning in his verdicts: “Corruption in the art world takes many forms, and silence is among the most corroding.” Warhol After Warhol is a warning against silence — a cool, lucid rebuke of art-world inscrutability. One longs for a poetic justice that is ultimately elusive — but then the book is its own small form of retribution.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.