Pittsburgh

Over the past few decades, Pittsburgh has become the poster boy for industrial transformation, going from Steel City to shiny hi-tech hub. But

one thing that has not changed is the local argot. “I have landed among the Yinzers,” my friend Damir Marusic, who is an op-ed editor at the Washington Post, proudly texted me when he arrived in Pittsburgh. Marusic is a fast learner. “Yinzer” remains the endonym of preference in Pittsburgh, where it was derived more than a century ago from the second-person plural pronoun by Ulster immigrants and shared with the later blue-collar workers from Central and Eastern Europe who labored in the hulking mills along the Monongahela. I’m not going to say that my own childhood in Pittsburgh was like something out of Coketown in Dickens’s Hard Times, but I can still recall the flames licking the sky and the clouds of pollution emitted by the towering smokestacks. Donald Trump may be nostalgic for those days, but I’m not.

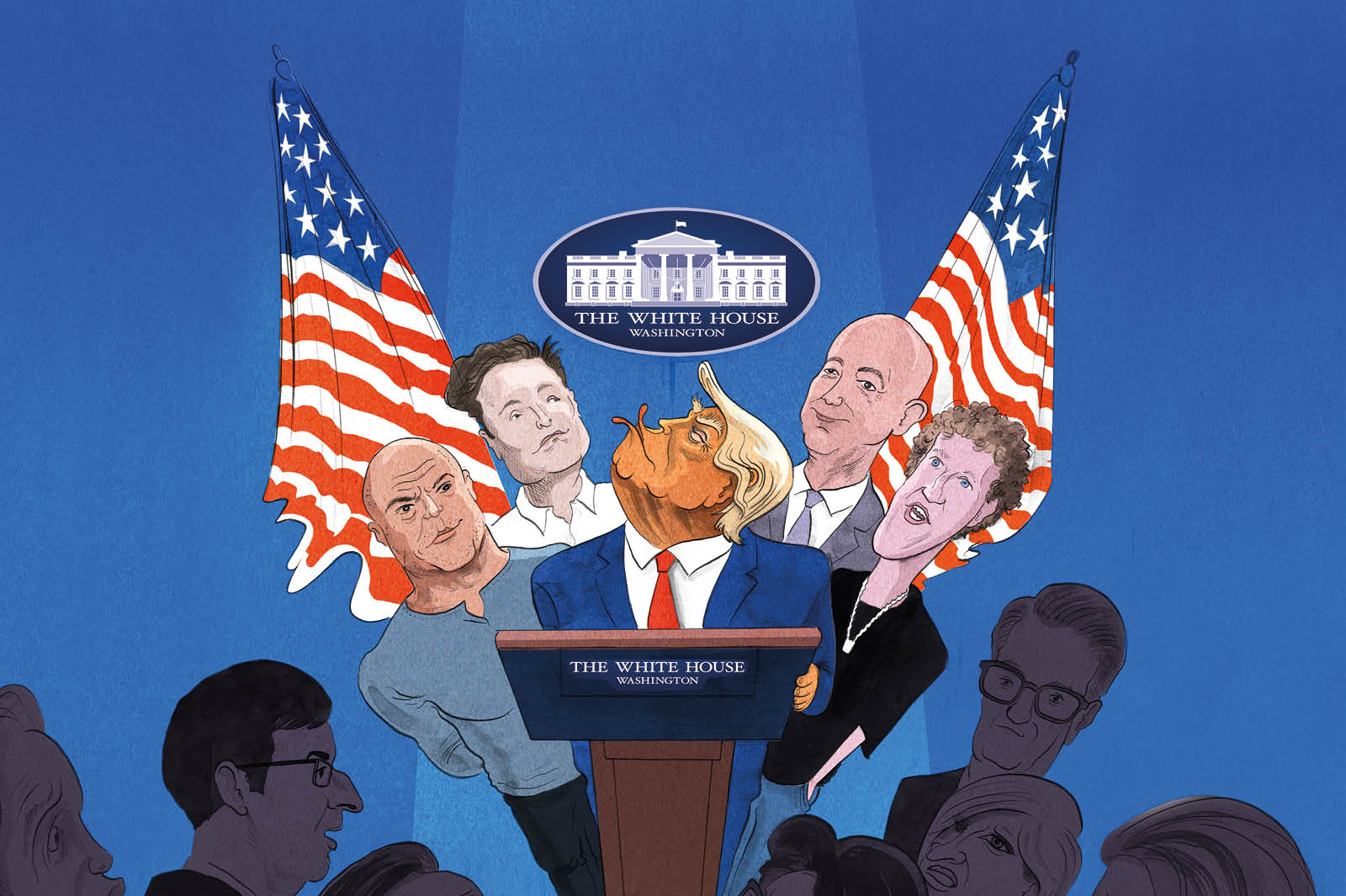

As it happens, Trump, or, if you prefer, Trumpism, was the subject of a session on my new book America Last: The Right’s Century-Long Romance With Foreign Dictators at the University of Pittsburgh, which Marusic and Jennifer Brick Murtazashvili, a scholar of Central Asia, moderated. In it, I argue that the right, more often than not, has displayed a penchant for venerating foreign autocrats, ranging from Kaiser Wilhelm to Viktor Orbán, and viewed them as models for America itself. The satirist and journalist H.L. Mencken, for example, wrote a piece for the Atlantic in 1915 suggesting that America would benefit from being conquered by Wilhelmine Germany, and scoffed at the notion that American democracy was a good thing.

In the 1930s, Mencken, Charles Lindbergh and others opposed American entry into World War Two, calling for “America First” — a slogan Woodrow Wilson pioneered in the 1916 election, when he claimed that he would keep America out of war. Today, Trump avers that he can end the Ukraine war in less than twenty-four hours and opposes aiding the doughty Ukrainians in their struggle against Vladimir Putin’s genocidal war. To my ear, it all sounds like 1940 redux, when the GOP battled against aiding Great Britain in its battle against the Nazis — a theme that Robert Kagan recently sounded in the Washington Post, though he failed to give President Joe Biden sufficient credit for bolstering NATO and standing up to Putin’s aggression.

Compared to my appearance on C-Span’s Washington Journal, where hostile telephone callers accused me, among other epithets, of being a “liar and a deceiver,” the queries at Pitt were fairly gentle. In other venues, however, as I’ve talked about the book, I’ve frequently been asked why I didn’t recount the sins of the left. Given that the late scholar Paul Hollander had already offered a definitive chronicle of the iniquities of the left in his 1981 book Political Pilgrims, which looked at everything from worship of Stalin to Fidel Castro, I couldn’t help feeling that this would be like carrying coals to Newcastle. But the book’s reception among some has brought home to me the extent to which the left has rediscovered Cold-War liberalism as its bête noire. A reviewer in the Washington Post accused me of running the danger of inadvertently exonerating Cold-War liberalism by highlighting the deficiencies of the right. I’m not sure that was my intention, but if I’m charged with being a Cold-War liberal, well, I’m more than happy to plead guilty.

The origins of this new war over the Cold War, I think, can be traced to Yale professor Samuel Moyn’s Liberalism Against Itself. The real enemy of the

left, it seems, isn’t Trump’s ambition to crack down on American society, but liberals who toady to state power. In the London Review of Books, Stephen Holmes dismantles Moyn, pointing out that he writes “Cold War liberals’ ‘hatred of Jacobin radicalism’ was so extreme that they could see nothing even remotely emancipatory about the Terror in 1793.” Gulp. Who knew that Lionel Trilling and Isaiah Berlin were the enemies of true freedom and liberty?

The left has made inroads in Pittsburgh, where Congresswoman Summer Lee hasn’t simply been criticizing Israel for its war in Gaza, but going much further — employing what an open letter from forty area rabbis and cantors calls “openly antisemitic” language. Lee refused to grant an interview to the Jewish Pittsburgh Chronicle, after promising to give one, and in April faced a tough primary challenge from fellow Democrat Bhavini Patel, a mainstream Democrat. For Biden, the deluge of criticism from the progressives over Gaza is more than a headache. It could prove an electoral landmine in Michigan and elsewhere.

Trump, though, remains his own worst enemy. As bloodcurdling as I may find his declarations of a “bloodbath” to be, his very extremism is likely to push Biden over the finish line. And it would be churlish of me not to express my own gratitude to Trump for inviting Viktor Orbán to Mar-a-Lago in March for a summit meeting. Book sales of America Last have been soaring ever since.

Jacob Heilbrunn’s America Last: The Right’s Century-Long Romance with Foreign Dictators (W.W. Norton) is out now. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply