Dr. Mehmet Oz has conceded to John Fetterman but has yet to say anything publicly, probably because, like many Republicans — myself included — he’s just not sure what to say.

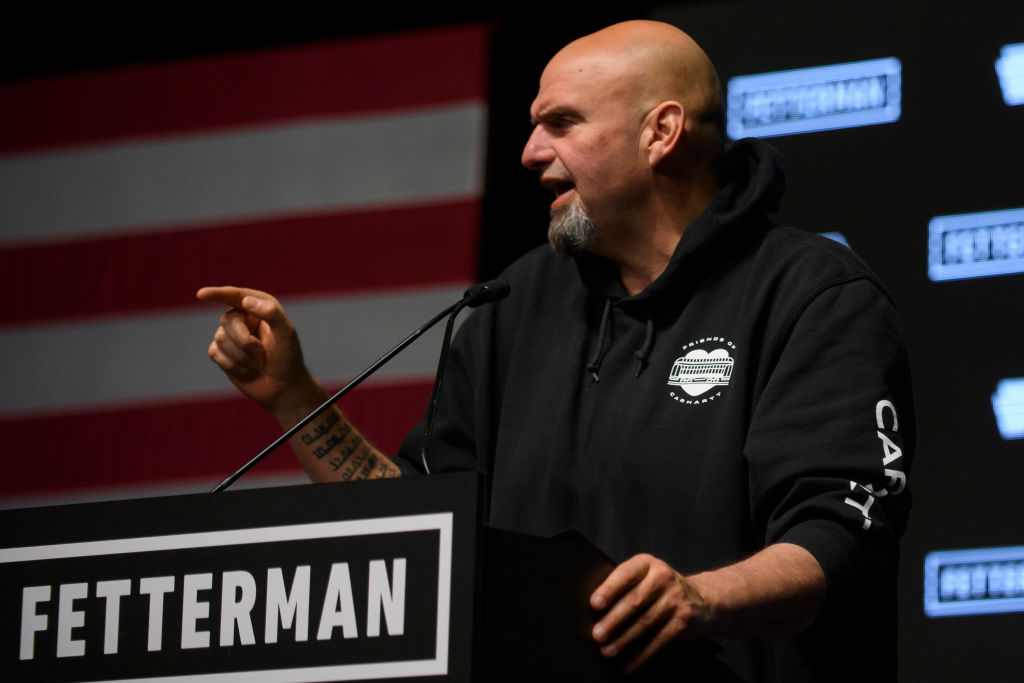

How could Fetterman, a tattooed, scowling, sloppily dressed goon with a concerning and unsightly neck lump (when I Googled his name, “Fetterman neck” was the third suggested search term), whose debate performance a mere two weeks ago was nothing short of pathetic, possibly have defeated a polished, successful, well-spoken heart surgeon for US Senate?

Fetterman’s victory is almost unbelievable, until you zoom out and look at the state of Pennsylvania and most of the country. Reflecting on the rural Pennsylvania town in which I live, I think people who voted for Fetterman did so for a mix of reasons: they relate to him, his looks and style, and they don’t relate to Oz, who perhaps is a bit too polished. They perceived Fetterman as the target of a rich bully, and his “comeback” from a stroke as inspiring. They could also be one of the growing number of people struggling financially, and they viewed Fetterman’s vague, big government campaign promises to “guarantee healthcare” and provide affordable housing as easier, quicker relief to their present desperation than Oz’s more solution-oriented, policy-specific, “I’ll help you help yourself!” message.

Fetterman suffered a stroke a few months ago, rendering him unable to understand people or speak normally. In a sane world, these unfortunate limitations would have led him to withdraw from the race. The Democratic Party and voters would have understood that sound health is integral to a person’s work, and they would have supported an alternative candidate out of respect for Fetterman’s and their own party’s wellbeing.

But that didn’t happen. Instead, Fetterman owned his ill health and turned his stroke into another weapon with which to beat Oz. His campaign turned the tables on anyone who questioned whether his running for office while recovering from a stroke was advisable. Fetterman made himself a victim, and he became a hero for it.

“Of course I expected Oz and the GOP to weaponize my stroke and make fun of me for missing words here and there, but I honestly didn’t anticipate it getting this bad — especially from a doctor,” Fetterman said in an interview with People magazine. “While we’ve had some fun at Dr. Oz’s expense about being from New Jersey, the rule of thumb has always been: be funny, don’t be mean.”

The View accused Oz of “bullying a stroke victim” and called him “un-empathetic.” Fetterman’s wife Gisele portrayed herself as a tough but sensitive champion for her husband, and people evidently bought the type of “John Fetterman is a selfless, big-hearted leader just trying to make a difference but is being tormented by a mean rich doctor who doesn’t even live here” tripe the Washington Post excelled at:

Politics is mean and hard, and Gisele — soft Gisele, who cries three times over the course of this interview — had no choice but to get good at it: After her husband suffered a stroke four days before the Pennsylvania primary election last spring, she stepped up and became his surrogate, delivering his acceptance speech and campaigning across the state.

It’s also possible that undecided voters who lean right just weren’t convinced by what Oz was selling this time. People are accustomed to seeing Oz on television hocking weight loss pills — and though he was a successful heart surgeon prior to his television show, voters found it hard to trust him. The little guys who break their backs to barely make ends meet (real victims) and who feel forgotten and put-upon by “the man” may have found Fetterman more appealing than some rich guy who drinks wine at tailgates. Fetterman’s simple reiteration of “Oz is lying and he’s on TV” struck a chord in the same way President Trump’s plainspoken, repetitive rhetoric did. (The irony is that Fetterman’s win may very well end up costing Trump’s GOP control of the Senate.)

The places where Fetterman won big — Erie, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia — are full of suffering people and many victims of government policies plunging them into poverty. Erie “has a dramatically higher than average percentage of residents below the poverty line when compared to the rest of Pennsylvania,” reports welfareinfo.org. “One in five Pittsburgh residents lived in poverty in 2021,” reports CBS. Philadelphia’s poverty rate was 23.3 percent in 2019, “the third-highest in the US and well above the national average of 10.5 percent,” reports Axios.

When it comes time to cast a vote, whose fault it is doesn’t appear to drive voters’ decisions as much as what to do about it, NOW. And with many voters having paid minimal attention to the debates, candidates’ records and so forth (they’re too busy trying to survive), it’s reasonable to believe that Fetterman’s everyman persona and pie-in-the-sky, big government agenda — he’s advocated for expanding benefits and grant programs — attracted a huge swath of voters who rely on government, view spendy projects and programs as more effective than the conservative plan of cutting taxes, spending and regulation — and those who simply viewed Oz as an out-of-touch celebrity carpetbagger.