This article is in

The Spectator’s inaugural US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.

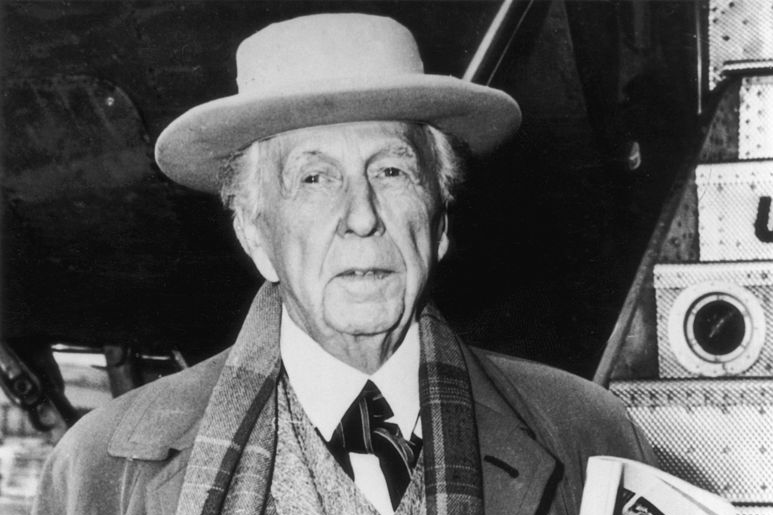

Paul Hendrickson’s last, and very fine, book was Hemingway’s Boat (2013). It was a nice conceit to see Hemingway’s life through his singular obsession with Pilar, the boat that he commissioned from a Brooklyn shipyard, and which remained the steadiest companion in his choppy voyage. The enormous life of Frank Lloyd Wright –– born two years after the Civil War, died in 1959 when Bobby Darin’s ‘Mack the Knife’ was a hit –– offers no such straightforward device. Every single Wright project could have become a novella. He was a philanderer, a fantasist, a liar, a cad, a spendthrift, an anti-Semite whose most famous clients –– Guggenheim and Kaufmann –– were Jewish, and a ‘narcissist and control freak’, at least according to the New York Post in a spasm of fastidiousness. But he was also America’s greatest architect, an incomparable creative genius.

It was the sight of a worker killed in the collapse of the neoclassical Capitol in Madison, Wisconsin that led Wright to ‘examine cornices critically’ and subsequently invent an architecture all his own. His best work came, astonishingly, in his ninth decade, when he built the Guggenheim in New York City (having essayed the concept in a sports car showroom on Park Avenue), and proposed the Mile High Illinois, a shard-like building 5,250 feet tall.

Wright’s combative attitude to clients and his lofty concept of the architect as quasi-divine seer made him the model for Howard Roark in Ayn Rand’s Fountainhead. His arrogance was epic. When a client complained that an ambitiously designed roof was leaking onto a desk, Wright said, ‘Move the desk.’ His artistic reach always exceeded the technical grasp of his builders. Edgar Kaufmann, the client of Falling Water, the Pennsylvania house on anybody’s list of Most Beautiful Buildings Ever, said the design was a ‘triumph of imagination over materials’.

Despite the superabundant richness of the sources, Wright presents a biographer with as many obstacles as opportunities. There have been countless art historical monographs and many very sound lives in recent years: Brendan Gill in 1987, Meryle Secrest in 1998 and Ada Louise Huxtable in 2004. Meanwhile, Nancy Horan published a bonkbuster novel called Loving Frank in 2007. And then there is Wright’s own Autobiography, first published in 1932 and then enlarged in size and ambition over many subsequent editions. The Rizzoli edition of his letters runs to five volumes. But Hendrickson is attempting something else.

Plagued by Fire is not conventional biography, nor is it art history. Instead it is a ‘kind of synecdoche, with selected pockets in a life standing for the oceanic whole of that life’. As Wright cultivated an aura of hokey bardic mysticism, I suspect there may have been a bit of spirit possession involved at some stage of the writing: Hendrickson’s story goes backwards and forwards in time and, ‘synecdoche’ or not, this treatment can become rambling and repetitive.

As he did with Hemingway’s Boat, Hendrickson isolates a single episode to explain his subject. This was an event destructive, not creative. On August 15, 1914, while Wright was away in Chicago, a servant from Barbados called Julian Carlton went berserk at Wright’s Taliesin studio-compound in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Using a shingling axe, Carlton killed Mamah Borthwick (with whom Wright was living ‘indecently’), her children and several workers. He then set a gasoline fire to destroy the evidence of his atrocity. For a man with Wright’s martyr complex, an ample sense of the symbolic, and a genius for (re)invention, this appalling calamity inspired complex and recurrent responses. Hence Hendrickson’s title.

But one returns always to the glorious, bravura performance that was Wright’s life. He wrote his autobiography in Thoreau-like seclusion in a Minnesota hut. He did jail time under the Mann Act for smuggling women over state lines. His Taliesin studio-compounds (one in Wisconsin, one in Arizona) were, according to Ada Louise Huxtable, a ‘shameless scam’. Wright created sex rotas for his student-disciples who were, in fact, underpaid and over-exploited interns. Certainly, Taliesin would not have passed scrutiny in the age of #MeToo. He also invented his name: he changed the given ‘Lincoln’ to ‘Lloyd’, so as to appear more authentically Welsh and thus arcane. (Taliesin was a sixth-century Brythonic poet.)

Wright’s dress sense was extraordinary: a gardenia boutonnière, a Malacca walking stick, capes, scarves, eccentric trousers, porkpie hats, high starched collars, and white shoes with lifts. Hendrickson suggests that Wright may have suppressed an early homoerotic episode with colleague Cecil Corwin, but since this suspicion is based on the ineffable chat-up line, ‘Come home with me tonight and we’ll concertize with my grand piano’, I am not so sure.

Hendrickson was a writer for the Washington Post’s popular Style section, and now teaches writing at the University of Pennsylvania. His easygoing and conversational manner disguises impressive research in a sprawling book about a sprawling life. It is an amiable and enjoyable read if, on occasion, a little too nudge-nudge and wink-wink. Unfortunately, the lines are set to a length that makes the reading physically uncomfortable.

Hemingway’s Boat floated to the top of The New York Times bestseller list and was happily becalmed there. If that doesn’t happen to Plagued by Fire, there will be two reasons. One, it is not quite so good a book. Two, our taste for XXL 20th-century American heroes may at last be in decline. I have just seen a Frank Lloyd Wright house for sale in New Jersey, price $995,000.

This article is in The Spectator’s inaugural US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.