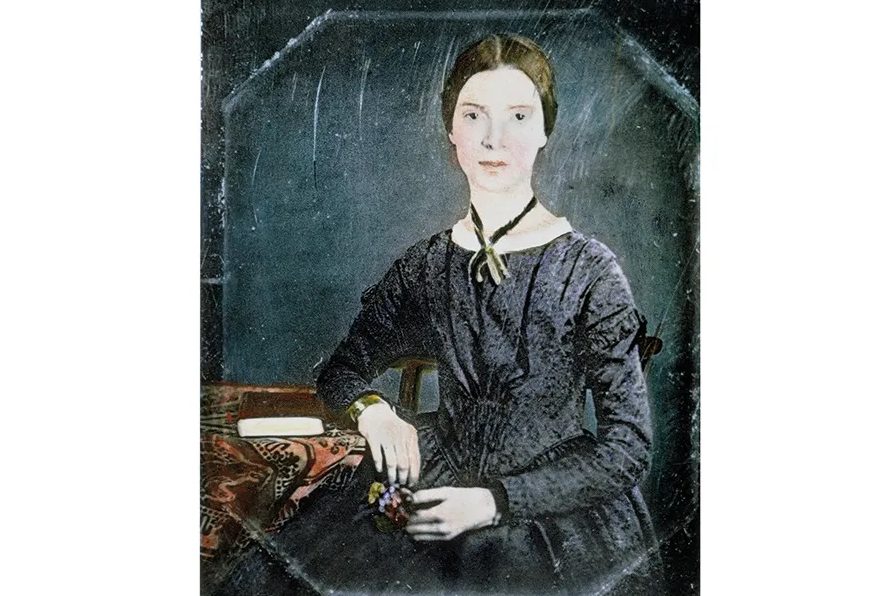

This is fanciful, I know, but I can’t help wondering about the great poetry that will surely be written in the early 2060s. Think about it: in the early 1960s, Sylvia Plath had her great creative outpouring, waking at 4 am each day to work on the “Ariel” poems that would make her name. Exactly 100 years earlier, Emily Dickinson was in full spate, writing 295 poems in 1863 alone. (Her total oeuvre amounts to nearly 1,800 poems, most of them unpublished during her lifetime.) The concentrated intensity with which these two women produced their best work has the quality of a natural phenomenon: a butterfly migration or a swarm of plankton ablaze with bioluminescence.

To read The Letters of Emily Dickinson is to experience this phenomenon in real-time. Cristianne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell’s edition is the first since Thomas H. Johnson and Theodora Ward’s in 1958. Along with eighty letters that have been discovered or radically re-edited, Miller and Mitchell have taken the inspired decision to add all of the 200-plus poems that Dickinson sent to various correspondents with no prose accompaniment (Johnson and Ward include just twenty-four).

When you reach the early 1860s, these letter-poems come thick and fast, urgent dispatches from Dickinson’s darkly brilliant gift. Take poem 477, which is about death, sent in 1862 to Dickinson’s sister-in-law Susan. It begins:

He fumbles at your Soul As Players at the Keys Before they drop full Music on — He stuns you by degrees

Imagine receiving that through the post, no explanation, no additional text.

Dickinson was just thirty-two when she wrote those lines. The letters testify to how often her shortish life was touched by death, beginning with her friend Sophia Holland, who died when Dickinson was fourteen. The casualties are a nineteenth-century litany of typhus, “brain congestion” and tuberculosis, but Dickinson was perhaps more than usually affected by these brutally routine losses: “I think of the grave very often, and how much it has got of mine, and whether I can ever stop it from carrying off what I love.”

The surge in productivity in the early 1860s was preceded by a major downswing in her mood: “I had a terror — since September — I could tell to none — and so I sing, as the Boy does by the Burying Ground, because I am afraid,” she wrote to her mentor Thomas Wentworth Higginson in April 1862. Dickinson is famous for her reclusive habits and mental fragility, diagnosed retrospectively as anxiety, agoraphobia, epilepsy and even autism. But in their introduction, the editors make a case for revising the image of Dickinson shut up in her bedroom, dressed in white. She lived with her parents and sister Vinnie for most of her life, and spent long hours nursing her chronically ill mother. “She also traveled more, until as late as 1865, and saw more people than popular writing about the poet claims.”

What is obvious from the letters and the poetry is that the minor key was only one of many modes for Dickinson. The great pleasure of her correspondence is its variety. Dickinson the clownish wit is there from childhood, reporting, aged twelve, to her brother Austin that “the chickens grow very fast I am afraid they will be so large you cannot perceive them with the naked Eye when you get home.” Years later, as a fond aunt, she gives an approving account of her four-year-old nephew: “Ned tells that the Clock purrs and the Kitten ticks. He inherits his Uncle Emily’s ardor for the lie.” The lively, tender dispatches she sent throughout her life to her younger cousins, Louisa and Frances Norcross, are full of domestic detail about living in Amherst. It was to these women that Dickinson sent her last letter before she died in 1886, aged fifty-five. It read simply: “Little Cousins, ‘Called back.’ Emily.”

Then there is the Dickinson who conducted correspondence with various intellectual figures of her day, including Samuel Bowles, the editor of the Springfield Republican, and fellow writer Helen Hunt Jackson (H.H.), who repeatedly urges Dickinson to publish her work. “You are a great poet,” Jackson tells her, “and it is a wrong to the day you live in that you will not sing aloud. When you are what men call dead, you will be sorry you were so stingy.” (This edition includes the handful of extant letters from Dickinson’s correspondents, and a few significant letters written about her.) And there is Dickinson the sexual submissive, in the three famously cryptic letters to an unidentified “Master,” and the drafts of love letters she wrote to the Massachusetts Supreme Court Justice Otis Lord: “The Creek turns Sea at thoughts of thee… Incarcerate me in yourself — that will punish me…”

Above all, perhaps, there is Dickinson the gardener, full of reverent glee for the glories of the natural world. However reclusive she might have been, she clearly spent a great deal of time outside. After returning from eye treatment in Cambridge in 1865, she writes: “For the first few weeks I did nothing but comfort my plants, till now their small green cheeks are wreathed with smiles.” Here, as in her poetry, the natural world is charmingly anthropomorphized. Another advantage of mixing the poems in with the letters is that you can clearly see the traffic between the two forms, as favorite images, words and phrases are repeated and refined. The prose of the letters frequently breaks into something closer to metered verse, with rhythmic emphasis from Dickinson’s signature dash.

Many letters were brief notes accompanying a pressed or fresh flower. Dickinson emerges as a thoughtful friend, remembering children’s birthdays and the anniversaries of significant deaths. For much of her life, she was conducting most of her relationships on the page, and mixed in with the long, carefully crafted letters are single-sentence notes akin to today’s texts. (She would have made a superlative tweeter.) “Dear Mary, You might not know I remembered you, unless I told you so — Emily,” runs one letter in its entirety. Shorter still, and archly affectionate: “Only Woman in the World, Accept a Julep.”

Dickinson the gardener is full of reverent glee for the glories of the natural world

The Only Woman in the World was the woman next door — her sister-in-law Susan Gilbert Dickinson, recipient of “He fumbles at your Soul” as well as the majority of Dickinson’s letter-poems and more straight letters. We know so much and yet so little about this relationship. Their friendship began in earnest in 1850. In 1856, Susan married Dickinson’s brother, Austin. The women lived in adjacent houses until Emily’s death, and it was Susan who prepared Dickinson’s body for burial. Perhaps their relationship started out as a love affair. Emily’s early letters are certainly passionate: “Susie, will you indeed come home next Saturday, and be my own again, and kiss me as you used to?” Perhaps the love was unrequited or lopsided. Intensity was a byword in so many of Dickinson’s relationships, and she repeatedly pesters her correspondents for replies. “I’ve expected a letter from you every day this week, but have been disappointed,” runs a typical plea to Austin. By her fifties, she’s wise to the downside of this behavior, writing to Otis Lord: “Oh, my too beloved, save me from the idolatry which would crush us both.”

Possibly Dickinson and Susan enjoyed one of history’s great editor-reader relationships. There are almost no extant replies from Susan to the onslaught of poems, but in one we do have, she gives a frank appraisal of the poetry’s merits. Dickinson certainly revered her friend’s mind. “With the exception of Shakespeare,” she tells her, “you have told me of more knowledge than any one living.”

Complicating the picture is the bizarre snow job practiced on the letters by an early editor, Mabel Loomis Todd. She was Austin’s lover, and their thirteen-year affair (begun in 1882) was a source of great pain to Susan. Todd in turn resented her lover’s wife. When preparing Dickinson’s letters for print, she omitted material from transcriptions, and it seems likely that either she or Austin were responsible for the many erasures and alterations in Dickinson’s early letters to her brother. These erasures all relate to mention of Susan — the removal of her name, or a pronoun altered so that “she” or “her” can become “he” or “him.” The editors have done a meticulous job of mending these mad mutilations wherever possible, with clear notation and explanatory text.

Letters have also been re-dated according to new data about local weather patterns, and the scrupulous notes draw our attention to Dickinson’s wider social and political context. The publicity surrounding the edition promotes Dickinson as “a poet firmly embedded in the political and literary currents of her time.” Ultimately, this quest tells us more about our present-day values than it does about Dickinson herself. Like Plath, she will always remain a bit of a mystery, no matter how loudly the engine of academia hisses and clanks. Which is probably exactly how she’d like it. “You remember my ideal cat has always a huge rat in its mouth, just going out of sight — though going out of sight in itself has a peculiar charm,” she writes to her Norcross cousins in 1876. “It is true that the unknown is the largest need of the intellect, though for it, no one thinks to thank God.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply