Perusing the listings of a recent auction, I noticed an intriguing, relatively flat piece of copper-plated cast iron featuring intricate foliate and geometric designs. It was a baluster designed by the firm of Adler & Sullivan in 1893 for the old Chicago Stock Exchange. The 1972 demolition of that building, thanks to the “urban renewal” undertaken by many progressive American cities during the mid-twentieth century, led to this bit of architectural salvage coming up at auction many years later.

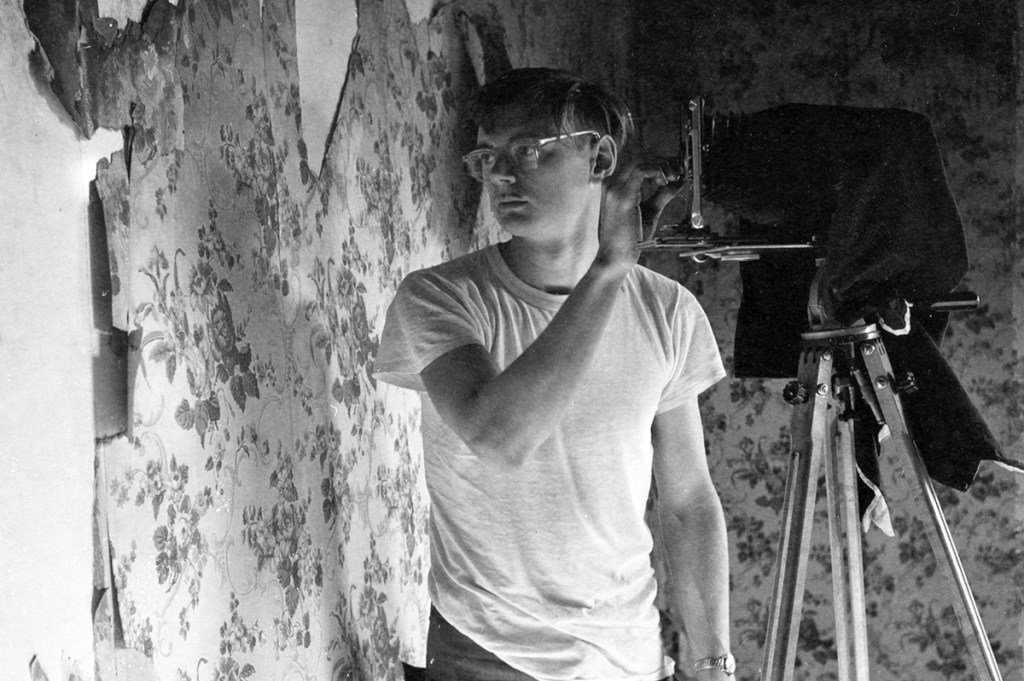

It also led to the death of an idealistic photographer and activist named Richard Nickel. When Nickel (born in 1928) was killed on April 13, 1972, his body was not recovered for weeks. It lay beneath a collapsed portion of the magnificent Stock Exchange building, which was being torn down to make way for a giant, boring glass-and-metal box. Nickel had gone to the demolition site that day, as he had to other sites over the years, to photograph the structure and to salvage whatever fragments he could of Chicago’s vanishing architectural heritage.

This was not a calling (or indeed an ending) that one might have predicted for a young Army veteran of moderate means from the Windy City’s Polish-American community. A lifelong interest in photography led Nickel to study it more seriously at the Illinois Institute of Design in the 1950s. There, he was given an assignment to photograph Chicago-area buildings designed by Louis Sullivan (1856-1924), one of America’s most brilliant and innovative architects.

What began as a class project, however, gradually became a crusade, and indeed an obsession. Many of the buildings Nickel photographed were falling into ruin, and then into the hands of developers, who inevitably tore them down. Gradually, Nickel added architectural activism and salvage to his efforts as he fought to stop the demolition of these structures, or at least to claim pieces of them for posterity. And while Nickel documented and championed buildings by many different architects, none were so dear to him as Sullivan’s.

Although lesser known than his famous protégé Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Sullivan is among the most influential figures in the history of American design. Sullivan argued that America needed its own unique architectural style, one whose ornamentation was drawn from the observation of nature. In his seminal essay “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered” (1896), composed when the first skyscrapers were appearing on the American skyline, Sullivan famously posited that “form ever follows function,” an imperative with which architects and designers have grappled ever since.

Sullivan arrived in Chicago from Boston in 1873, just two years after the Great Chicago Fire obliterated most of the city’s downtown. As it rose from the ashes, the metropolis sought to create a new identity for itself, something that aspired to be more than a conglomeration of stockyards and slaughterhouses. In partnership with architect Dankmar Adler and later on his own, Sullivan provided Chicago with just that identity, creating innumerable innovatory structures, from theaters to commercial towers to private residences.

Yet beginning in the 1950s, the city of Chicago repaid that legacy by systematically knocking down many of Sullivan’s creations. His magnificent 1891 Garrick Theater, for example, was gone by 1961, replaced with a parking garage; the Stock Exchange lasted only a bit longer. These and other Gilded Age buildings, built to last for centuries, in many cases did not make it to their one hundredth birthdays.

Fifty years have passed since the death of Richard Nickel and the destruction of the last Sullivan that he tried to save. Capturing Louis Sullivan: What Richard Nickel Saw, which opened recently at Chicago’s Driehaus Museum, reexamines this unlikely partnership by placing Nickel’s photographs alongside Sullivan’s architectural fragments.

The exhibition’s curator, David A. Hanks, served alongside Nickel in the 1970s on the Advisory Committee to the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, going out to look at threatened buildings and discussing whether to recommend that they be preserved.

At the time, Hanks was a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago. “Nickel was shy,” Hanks recalled, “and uneasy in the presence of institutional authority. I represented an element that Richard was often angry at, and for good reason, because he saw that institutional elements were tearing down Chicago’s architecture.”

Both at home and abroad, the destruction of the work of Sullivan and others during this period was keenly felt, and it continues to rankle. “With Sullivan, [Louis Comfort] Tiffany and others,” remarked Anna M. Musci, executive director of the Driehaus Museum, “these designers and artists were creating a new American decorative language and cultural heritage. And if it goes into the dumpster, so does a lot of understanding of that cultural heritage.”

“The buildings were coming down so fast,” Hanks remembered, “that Richard was constantly running around from one to another to document them. And as a curator, I was collecting material from all over: there were things constantly being brought into the museum, and I had to raise the funds to acquire them, and try to find storage space for them. So many buildings were coming down, you just couldn’t believe it.”

A former paratrooper, Nickel had no fear of heights, a trait that came in handy when photographing the roof of a building or clambering about rescuing fragments of ornamentation. “He was devoted to preserving them,” Hanks explained, “not because they could substitute for the buildings themselves, but because they were a reminder along with his photographs of the importance of the buildings.”

“In Richard Nickel’s photographs,” observed Musci, “he didn’t take artistic license: he wanted people to see the building just as it was: as realistic and in as much detail as you could see it, during what was essentially the death of that building. And then you see a piece of that building, on a pedestal right in front of the photograph, and you get a better sense of what that ornament did.”

“What was striking to me,” noted Musci, “was the fact that he and all of the people involved took inspiration from the idea of ornament. Their lives were all consumed with this idea, that people should never forget the ornamental work of people like Sullivan, as part of our cultural heritage here in Chicago.”

Alongside such relics however, the stories themselves need to be retold, or they are soon forgotten. “One reason I wanted to do this exhibition,” explained Hanks, “was that it was important to retell Richard’s story. It’s a story that needs to be remembered. That story is now fifty years old, and there’s a generation or two that has never heard of him. He’ll be completely new to them, and that’s the audience that I was reaching for.”

As is often the case with the stories of great figures, as time goes on hagiography can easily weave its way in. There is Sullivan, a prophet without honor in his own city. There is Nickel, the sensitive everyman, who fervently takes up Sullivan’s cause and dies the death of a martyr. Yet the life of Richard Nickel is not simply a sad chapter in the history of lost art.

“Richard Nickel was a genius, really,” opines Musci. “He was someone who could focus at the level that he did, to work on one hand with documentation and salvage, and on the other with advocacy and activism. He really did help to change how buildings are saved.”

Despite the failure to save the particular building that ultimately killed him, Nickel’s efforts managed to bring that particular building of Sullivan’s to a much wider audience. “In some ways, it’s ironic that so much of the Chicago Stock Exchange has been preserved,” observed Hanks. “The trading room is at the Art Institute, the staircase is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and there are fragments of the building in museums all over the world. The building may be gone, but at least there are pieces of it everywhere.”

As for that aforementioned baluster from the demolished Exchange, it sold for three times its low estimate. Sullivan might be surprised that this small example of his work would be worth so much in the marketplace. One suspects that Nickel, however, would not.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2022 World edition.