Ahead of the Chinese new year holiday, Beijing has been intervening to prop up the country’s stock markets. Regulators have tightened market trading conditions, and this week the head of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, Yi Huiman, was fired abruptly, presumably as the fall-guy for the relentless decline in the markets, which have lost about $6 trillion in value since the end of 2021.

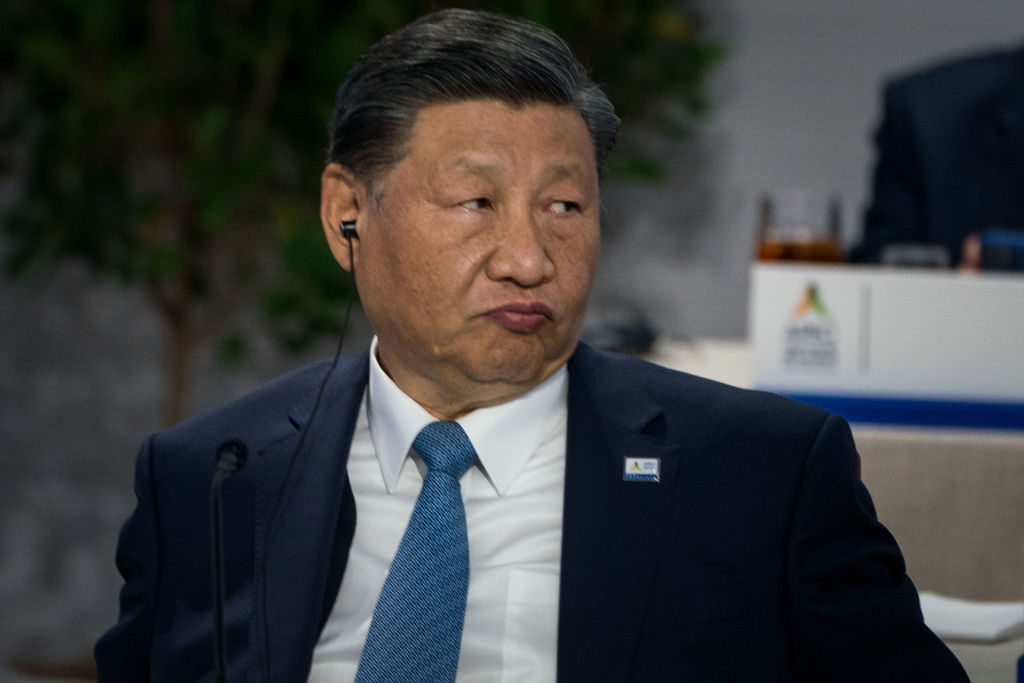

There is a palpable concern about financial instability in China that travels all the way up to Xi Jinping

Chinese equity prices have touched their lowest levels since 2018, and are not far from the lows reached in the 2015-16 financial crisis. Mr. Yi’s two predecessors were also fired in 2015 and 2019. Whether the authorities now succeed in reversing the rout is important, but what they are up to and why calls for some deeper thought.

China’s stock market is curious. It’s the second biggest in the world, and the government has been urging domestic firms, especially since 2020, to raise capital at home. But in terms of global impact, it hardly figures, and certainly compared with the US. As a marker of domestic economic performance, it is also of little significance. Yet, it matters in the current circumstances.

There is a palpable concern about financial instability in China that travels all the way up to Xi Jinping. There is an angst that the market slump is a weathervane for the erosion of confidence in the economy and in the traditional belief in the decisiveness of Chinese policymakers. For the last several months they have demonstrated that they are not on top of the stock market’s decline, nor, more to the point, of the underlying causes of the slide in confidence.

This bout of financial turbulence is quite different from the one which tore through the financial system eight to nine years ago. That was the result of excessive speculation and leverage. This speculation was encouraged by state-owned media, who called on people to buy stocks for the good of the economy, and by the lifting of government equity purchase restrictions on local government and civil service pension funds. The equity market bubble popped in spectacular fashion. But as the government intervened financially and imposed restrictions, the markets stabilized and then recovered.

The almost continuous fall in valuations since late 2021, and especially in the last six to nine months, though, is a different beast. This is much less about a post bubble reaction and market panic, and much more about a slow-motion but persistent loss of confidence in China’s economic growth prospects, and in the willingness of the government to create a comprehensive policy agenda to address its biggest problems.

Professional investors and economic experts have been expressing concern about several unaddressed or sidelined shortcomings in China’s economic model and policymaking for some time. But the most urgent problems reside in the real estate sector, local government debt and finances, and ultimately, the unrecognized losses that both are inflicting on banks and other financial institutions. The government has introduced a variety of piecemeal measures to try and stabilize banks and local governments, but to no lasting effect, and it still lacks a comprehensive plan that would stabilize and lessen the financial risks which it says are a matter of national security.

The recently published IMF annual Article IV Report on China has as its centerpiece a detailed review of the country’s property, local government finances, and rising financial sector risks. The report acknowledges what the authorities have done but calls for much more joined-up and holistic policy measures.

It expects prolonged difficulties in reducing excess inventory and supply in real estate. This is exacerbated by government resistance to market-clearing mechanisms such as bankruptcy. The report puts forward a plan to complete unfinished housing units for owners nationwide, estimating that this would cost Beijing 5 percent of GDP, or $1 trillion, excluding recapitalization costs for developers and banks.

To improve the structure of public finances, especially of local governments, and bring down debt, the IMF recommends a fiscal consolidation package that would tighten budgets by 5.5 percent of GDP, along with considerable restructuring of local government balance sheets, debt write-offs and asset sales — all of which are politically difficult.

It is not obvious why Beijing, long known for its decisiveness, appears to be so restrained in coming forward with convincing and comprehensive plans to address some of the big issues. China watchers have been hoping for almost six months to hear an announcement from the Politburo about the calling of the so-called Third Plenum of the CCP’s current 20th Congress. This is a forum typically known for in-depth analysis of the economy and the government’s thinking about medium-term strategies, but there has been no word about when or whether it will be held.

The year of the dragon is supposed to usher in a good time for fresh starts. Yet the government has to go beyond optimistic messages and vague promises. It must embrace and announce persuasive, comprehensive strategies to rebuild confidence and trust with homeowners, investors and foreigners. If it fails, any market bounces will quickly unravel, and China’s property and financial travails are likely to worsen.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply