My husband and I live in a rural village about an hour from London. The nearest grocery store is a twenty-minute drive. I haven’t ordered takeout in six years. I spent a good few years craving Thai and Chinese food, and then we stumbled across a recipe in the Daily Telegraph for homemade dim sum. “But we don’t have a bamboo steamer,” I said. This seemed an insurmountable hurdle. “We can just get one on Amazon,” said my husband. And so we did.

Making dim sum at home has been a pleasure beyond my expectations. They are surprisingly simple to make, and once you get the hang of it, not too laborious. The recipe we use is a classic combination of pork and steamed cabbage. The minced pork marinates in light and dark soy sauce, light for the saltiness and dark for the syrupy sweet — as well as sesame oil, Shaoxing rice wine, fresh ginger, ground white pepper, a bit of powdered vegetable stock and sea salt. The recipe calls for squeezing the pork in your hands, so all the ingredients are pressed through it. The mixture is then thrown into your mix- ing bowl. This last trick forms the meat into a compact ball; it’s all quite a lot of fun.

Chopped Chinese leaf or white cabbage goes in next, and chopped fine green beans and scallions. These are squeezed into the meat as well, and the whole thing sits in the fridge for half an hour. When it’s time to assemble the dumplings, I take a teaspoon’s worth of the mixture and place it in the center of a dumpling wrapper. These can be homemade but the ones we buy in Chinatown are probably better. We then seal the wrappers around the filling with little crimping folds and place on a tray ready for steaming.

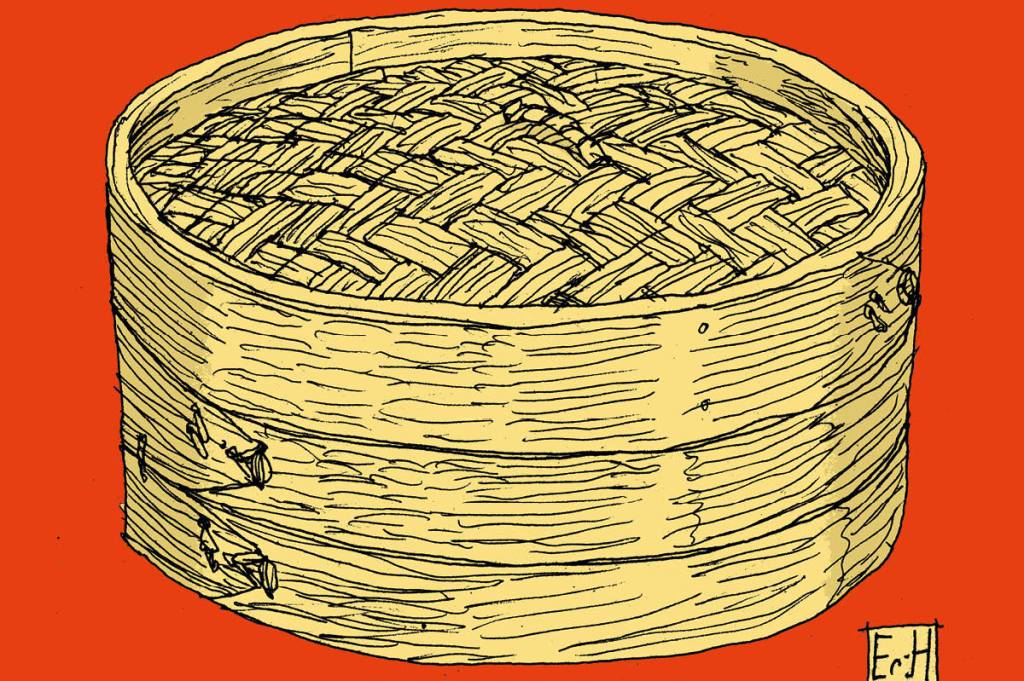

The bamboo steamer is the best part. Woven and round, a thing of beauty, it sits sedately inside our shallow cast-iron casserole dish. The boiling water beneath it doesn’t bubble violently — it emits a steady hiss and the steam rises through the bamboo and cooks the dumplings in ten minutes. It’s enchanting. You don’t even have to check on them partway through — they are always cooked to perfection in exactly ten minutes.

This method of steaming vegetables and meat together is ingenious and deeply satisfying. The Chinese have been doing it for at least a thousand years. Jiaozi dumplings are a favorite during New Year festivities, which take place this year on February 10. The lovely parcel shapes of these dumplings fit snugly inside your bowl like little gifts and are traditionally served just four at a time so that they “touch the heart, not fill the stomach.” My husband and I have failed to follow that particular tradition, consuming roughly three times that amount in one sitting.

In Jung Chang’s memoir Wild Swans, there’s a memorable story about dim sum which captures her family life and childhood in late twentieth-century China. She grew up during Mao’s Cultural Revolution, and she and her family were separated and forced into labor camps, with no knowing when or if they would see each other again. In one scene Chang is allowed a brief visit to her mother. When the visit is over, Chang’s mother walks her to the road where a truck is scheduled to pick her up. It is Chinese New Year in 1970, the tang-yuan have been made — little round dumplings, to symbolize family unity — and Chang and her mother are about to be separated again, perhaps forever. Chang’s mother can’t bear the idea of sending her daughter away on an empty stomach, so she runs back to get some dim sum. While she’s gone, the truck arrives. Chang has no choice — she must board the truck or face unknown but undoubtedly horrific consequences. As the truck drives away, Chang can just see her mother in the distance, running with the bowl of dumplings in her hands, then dropping the bowl and carrying on running toward the truck that is taking her daughter away. Whenever I eat dim sum, I think of that act of love by a mother for her daughter.

Chengdu is in Sichuan, where the classic crescent-shaped Zhong dumplings originate. In fact, many of the recipes that have traveled worldwide from China have come from Sichuan province. Sichuan is known in China as “the land of plenty.” Magnificent peaks rise above the Chengdu plains, where lush green valleys are fed by crisscrossing rivers and streams. Mountain peaks guard the northern border, and to the west lies the Tibetan plateau, with the steep gorges of the Yangtze River to the east. It is difficult to approach — the eighth-century poet Li Bai called the way to Sichuan “harder than the road to heaven.” An invading army would have found the road almost impassable. Despite the narrow way, people, food and trade seem to flow easily out of Sichuan and down the Yangtze River. It is less a cultural melting pot than a font, from which the flavors and traditions of southern Chinese cooking have flowed for over a millennium.

The Sichuanese are serious and methodical about flavor. English food writer and cook Fuchsia Dunlop trained in Sichuan and learned that there are twenty-three specific combinations of flavors in Sichuan cooking. Despite the region’s love of hot food, chilies didn’t make it there until the sixteenth century. They use Sichuan pepper instead, which is unlike any other flavor in the world. It’s a key ingredient in westernized dishes like Kung Pao Chicken, which my husband and I have also attempted to cook. It was so hot our tongues felt cold, I think because the Sichuan pepper oil has an anesthetic effect. We will keep trying out Sichuan dishes, possibly with less of the pepper oil. And of course, we’ll keep making Zhong dumplings which, in true Sichuan fashion, have managed to reach remote places. In our case, the little wrappers from Chinatown will travel in my husband’s coat pocket down the Hastings railway from Soho to Sussex.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply