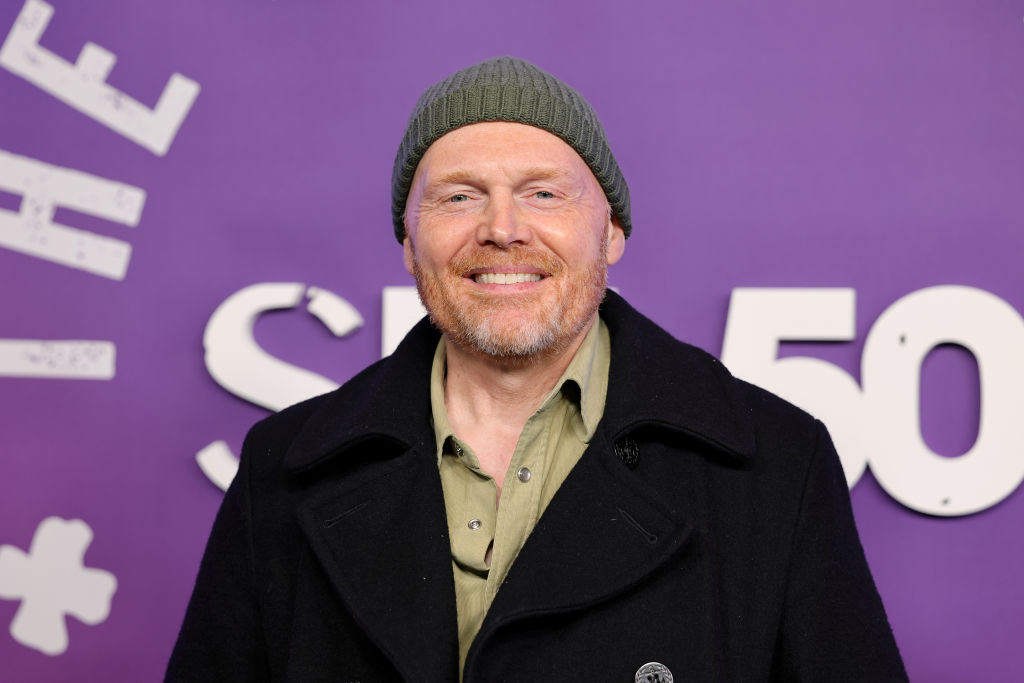

It’s a beautiful Saturday afternoon in Beverly Hills and Bill Maher — stand-up comedian, late-night television host, prophet of the great American silent majority — is ruminating on what the hell has gone wrong with the left: “It all comes, I think, from two terrible sources: bad parenting and insane universities. That’s where the craziness is coming from.”

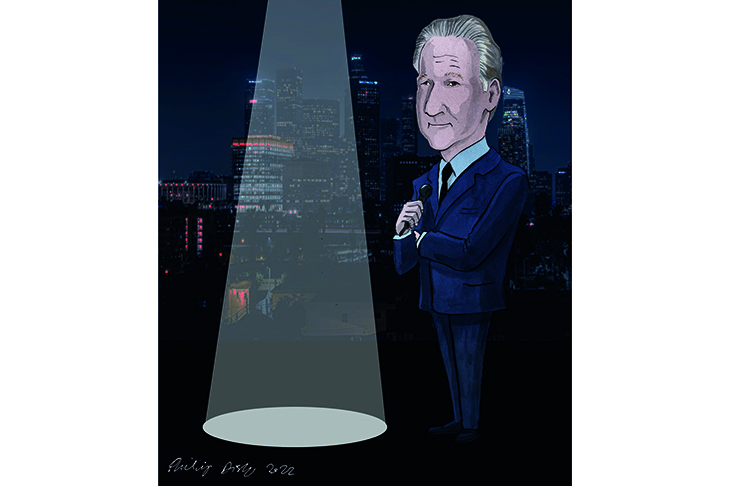

Maher is sitting with me in “Club Random,” the neon-light-festooned, decked-out bungalow he converted into a television studio in 2020, after social distancing requirements forced his weekly HBO show, Real Time with Bill Maher, to shoot remotely. Real Time is back to business as usual, and Club Random, replete with a fully stocked bar and pool table, has reverted once again to serving as a DIY studio, this time for the eponymous podcast in which Maher invites a fellow comedian over to light up a joint, pour a drink and shoot the shit.

Resuscitating the dying art of conversation has been Maher’s mission for almost three decades, ever since his show Politically Incorrect premiered on Comedy Central in the summer of 1993 (before moving to ABC in 1997). It was that blissful interregnum between the end of the Cold War and the start of the War on Terror, when politics no longer seemed to matter all that much. “People thought it was a terrible idea” to launch a show where celebrities, politicians, comedians and pundits debated current events, Maher recalls. “Politics was the most toxic issue you could approach, considered so uncool.” That Maher was uninhibited in expressing his own political views, a mix of social liberalism and libertarianism with the occasional dollop of fiscal conservatism and support for personal responsibility thrown in, was an added risk. “Let’s see,” Maher remembers responding to network executives who feared that his departure from the traditional studied political neutrality of late-night hosts would alienate viewers. “Maybe they’ll disagree with me and still not hate me.”

Nearly thirty years later, it’s safe to say that Maher’s formula has worked. Last September, HBO renewed his contract through 2024, by which time Maher — already the longest-serving late-night television host still on the air — will have completed twenty-one seasons with the cable network. It’s an impressive accomplishment, especially considering the cutthroat nature of the field. (Just a few weeks after our conversation, TBS announced that it was canceling Samantha Bee’s Full Frontal after seven seasons.) Maher isn’t shy about enjoying his celebrity status. When, upon entering “Club Random,” I approvingly liken his lair to a “man cave,” he promptly corrects me. “A man cave,” the proud bachelor says, “is for married men.” As if to underscore the distinction, a giant road sign warns those who enter, “PLAYMATES AT PLAY.” Knowing of Maher’s fondness for marijuana, I have brought him a peace offering: a joint purchased from one of LA’s finest pot dispensaries. As we settle down into a pair of red leather chairs and light up, Maher’s one-eyed dog Chico scurries about our feet.

To explain his point about the insanity of the universities and the impertinence of youth, Maher points behind him to a poster for a movie, One Credit Short, in which a younger Maher, playing an overgrown college student sporting a t-shirt emblazoned with a giant cannabis leaf, can be seen standing in a quad alongside an array of stock characters: a truculent administrator, a bossy professor, a perky coed, meathead frat boys. “OLD CAMPUS, NEW RULES” reads the tagline for the film, which, according to the credits, is a Merchant/Ivory production. As this odd detail suggests, One Credit Short is not a real movie; the poster, intended as a spoof of 1980s campus comedies, was a gift from Maher’s friends. (The verisimilitude of this fake film is enhanced by the poster for a real one, hanging right next to it, in which Maher actually did star, 1989’s Cannibal Women in the Avocado Jungle of Death.)

“That was never the Democrat of yore,” Maher says of the officious academic bureaucrats depicted on the poster, the type of person who has seemingly replaced blue-collar workers as the base of the Democratic Party. “The rich, stick-up-their-ass assholes that this guy with the pot symbol on his shirt wants to take the piss out of,” used to be Republicans. Today, Maher laments, “the young people are the prudes and don’t find anything funny.”

As a man whose job it is to be funny, Maher is confounded by this generational role-reversal. Completely at odds with his pot-smoking, bachelor lifestyle, Maher has unwittingly become a pop-cultural elder statesman, a lonely voice of sanity holding his own against a tide of younger, woker, invariably less funny late-night hosts interchangeable in their rote adherence to the progressive party line. This cultural trend toward overt political partisanship accelerated during the Trump years, when whole sectors of American society dropped any pretense of objectivity and pledged fealty to the “Resistance.” While the previous generation of late-night comedy titans — Johnny Carson, David Letterman, Jay Leno — certainly did not shy away from political humor, they avoided partisanship. Today’s hosts, by contrast, seem to take pleasure in alienating half the country on a nightly basis.

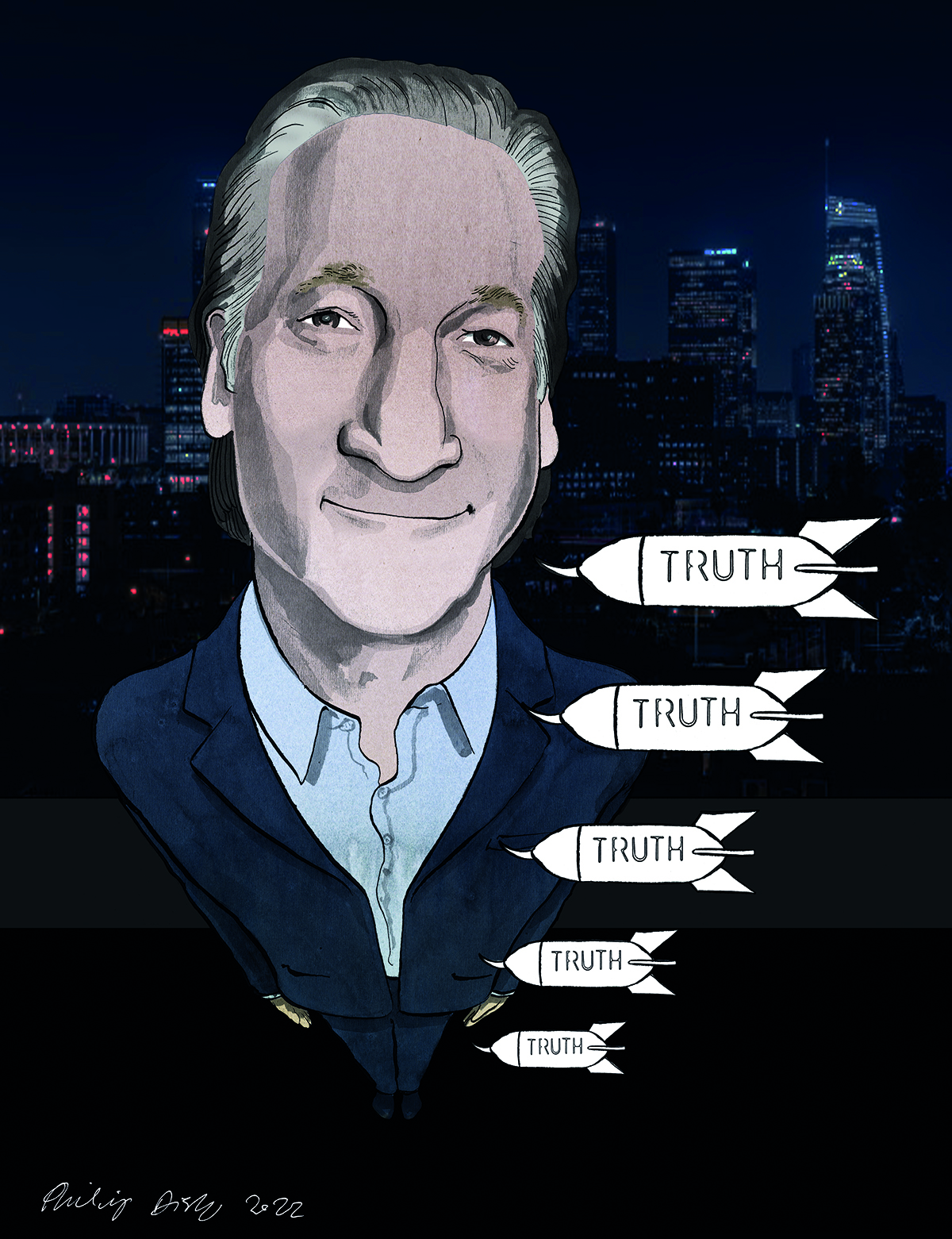

Amid this barren comedic landscape, Real Time has become an oasis for independent-minded Americans as tired of the left’s obnoxious sanctimony as they are of the right’s wild-eyed conspiracy-mongering. I have appeared twice on the show and can attest that it offers more rigorous political debate than any ostensibly “serious” cable news program. At a time when the mainstream media has become depressingly predictable in its conformity, Maher’s stubborn refusal to fall in line shows up in his tendency to say things that pierce through the noise. Usually, Maher drops these truth bombs during the show’s final editorial segment, in which he directly addresses the camera about a controversial subject. “I don’t feel like I’ve had to retract too many things, and a lot of things look pretty good in retrospect,” he says of his track record. “Sometimes on a weekly, monthly basis, I’ll do the editorial and everyone will throw a shit fit and then two weeks later, oh, you’re all saying it.”

A notable example of this phenomenon occurred in May, when Maher delivered an editorial about the dramatic uptick in transgender identification among young people. While acknowledging the reality of transgenderism and applauding societal acceptance of it, Maher said “It’s OK to ask questions about something that’s very new and involves children.” For this heresy, he was inevitably accused of transphobia, but then something interesting happened. Within three months, the New York Times, long an uncritical fount of transgender ideology, published a report giving voice to doctors concerned that children are being rushed into gender transition, an op-ed faulting activists on “the fringe left” for “reducing [women] to a mix of body parts and gender stereotypes,” and a news article detailing the exploits of an eighty-three-year-old transgender serial killer whose prior placement in a women’s shelter, according to one source, “seemed like a bad idea, given her history of killing women.”

Around the same time, both the actress Bette Midler and the singer Macy Gray expressed misgivings about the excesses of the transgender movement, with Midler tweeting in consternation, “they call us ‘birthing people’ and ‘menstruators’ and even ‘people with vaginas’!” and Gray telling Piers Morgan that “just because you go change your [body] parts, doesn’t make you a woman, sorry.” It was as if Maher had broken open a dam, and the pent-up sentiments of the moderate majority were finally pouring out.

Higher education and youth culture are two perennial bugbears of the American right, and Maher is at pains to deny that his antagonism toward both makes him a conservative. “This is not conservative, this is just common sense,” he says, in reference to how twentysomethings have gained the whip hand within so many American institutions. “Should youthful ideas be in the mix? Yes. Should their enthusiasm and idealism be in the mix? Yes. But should it be at the top of the pile and just obeyed? I think most woke ideas are things twenty-year-olds think, and because we have this bad parenting situation where they let the kids rule the roost, the ideas of children become the ideas of society. That’s how you wind up with ‘Anne Frank had white supremacy,’” he says, citing the recent Twitter kerfuffle over whether the Holocaust’s most famous victim was in fact the beneficiary of racial privilege to illustrate how ludicrous ideas from academia infect mainstream discourse.

“These kids today are always bitching about how there’s no good jobs,” he continues. “Yes, because you don’t have any useful skills. Because your major was film studies. They don’t take film studies in China. Or gender studies. Or sports marketing. Or communications. You learned nonsense that’s useless, that’s why there’s no jobs. ‘Immigrants are taking my job!’ Yeah, because they work harder, they care, they’re hungry, and you’re fat. End of scene.”

To hear it from Maher’s left-wing critics, riffs such as these on “kids today!” have reduced him to the proverbial old man yelling at the neighborhood children to stay off his lawn. His is indeed an ironic position for a child of the 1960s to find himself in, one that sets Maher apart from many of his fellow baby boomers, who typically cave without putting up a fight when confronted by their younger subordinates on any one of the myriad identity issues that have recently bedeviled American institutional life.

Maher’s retort to the criticism echoes that of Ronald Reagan, who famously said that it was not he who had left the Democratic Party, but the party that had left him. “We haven’t changed,” Maher asserts of himself and his fellow “old-school liberals,” who “still believe in things like a colorblind society. We don’t believe America is irredeemably racist… I can’t go back to 1860 and knock the mint julep out of their hands.” Maher points to the Middle East as an example of the left’s abandonment of liberal values. “The left has given up on Israel,” he says, a country that ought to earn liberal sympathy by dint of its being a “western democracy” in a region populated with despots and religious fanatics. As is so often the case, the anti-Israel phenomenon is “mostly a young people thing. Because they don’t think past this: the Palestinians are browner and poorer, so they must be the good guys… We always have to break things down into oppressed and oppressor.”

Maher traces his old-school liberalism to his childhood, growing up in New Jersey the son of a Jewish homemaker mother and a Catholic radio newsman father. Both of his parents were liberal Democrats during the halcyon days when Pope John XXIII was implementing liberal reforms, John F. Kennedy was the first Catholic president, “and all was right with the world.” Maher’s dad was a veteran of World War Two. “We got the family, we’re in the suburbs, the right guy is pope, the right guy is president, and then it all went to shit” with the Vietnam War, a string of shocking political assassinations and Watergate. “You could trace that devolution of hope and idealism from my own father that sort of simultaneously happened to America.”

While Maher harbored an early interest in politics, it was always as an observer, not a participant. “I might have gone to a McGovern rally in 1972,” he says with an air of bemused recollection, the joint in his hand a suddenly appropriate prop for reminiscing about the left-wing presidential candidate tarred with backing “acid, amnesty and abortion.” (Maher has given millions of dollars to various Democratic campaign committees over the years, a point the liberal critics who decry him as reactionary conveniently ignore.) When he worked the stand-up circuit in the late 1970s and early 1980s, political humor was “always in the mix.” But “sitcoms were ascendant” and he and his peers “all wanted to get on” one.

Maher decided to embrace his calling as a political animal in summer 1993, when he launched Politically Incorrect. Ultimately, his take-no-prisoners approach would be his undoing, when, a week after the September 11 terrorist attacks, he had the temerity to suggest that “cowardly” might not be the most suitable adjective to describe the terrorists who had violently commandeered airplanes and flown them into the Twin Towers. The worst that could be said about this remark was that it was needlessly pedantic. But it was a jingoistic time, feelings were raw, and the American public was hardly in the mood for nuance. White House press secretary Ari Fleischer denounced Maher from the podium, ominously warning that “people have to watch what they say and watch what they do,” and advertisers got the message. Maher was accused, absurdly, of expressing sympathy for the maniacs who had just murdered 3,000 people, and his show was booted off the air the following year.

Maher’s literal cancellation — in the old-fashioned sense of the word once reserved for the television industry — has made him an articulate critic of the more recent and broader cultural phenomenon that has crept into so many areas of American life. It has also endowed him with admirable empathy for those who have found themselves in similar straits. At one point during our conversation, the name of former NBC News anchor Brian Williams comes up, and I refer dismissively to his reputation for embellishing stories about his courage under fire. “Oh, for fuck’s sake,” Maher bristles. “I want to meet these perfect people, Jamie, who’ve never made a mistake. Everybody’s got something.” In July, Maher welcomed Chris Cuomo onto Real Time for the ex-CNN host’s first TV interview since the network fired him for providing advice to his older brother, disgraced former New York governor Andrew Cuomo, during the latter’s sexual harassment scandal. “Winona Ryder, great girl,” Maher says. “The way Hollywood just went absolutely apeshit because she shoplifted? Charlie Sheen has been accused of giving people AIDS and he gets a Super Bowl commercial.”

Maher’s critique of our societal craving for moral absolutism speaks to his larger capacity for adding the nuance so often missing from contemporary political debates. If Maher paved a trail in late-night comedy by being forthright about his political opinions, he has distinguished himself further by expressing opinions that vary from Democratic Party talking points. And it’s this independence that Maher believes to be the secret of his success. “People are looking for something that’s not catering to the excesses of the right, which of course we never did, but also of the left,” he tells me of his show. Other late-night hosts “pretty much cleave to whatever the dictums of the woke are. The worst thing that seems in their minds to happen to a human being would be to say something and have the studio audience not approve of it. Which is, as we know, certainly not the way I’ve run my business, and I have many clips to prove it.”

When I suggest that Maher open his stand-up routine at Indian-owned casinos with a land acknowledgement, offering his condolences to the local tribe and its ancestors, he seizes upon the idea. “If that doesn’t say it all about the left, that they have to just begin anything with an apology. I didn’t do anything. People I’ve never met. But let me just say I’m sorry for existing. The unbearable whiteness of my being. It’s a kink. It’s like wanting someone to dig their spiked heel into your nuts.”

Maher says he feels a “responsibility” to criticize the left more because, while “I’ve never been a team guy, never been a Democrat… I caucused with the left more. And still would, because Republicans are the party of no democracy, environmental blindness, fiscal hypocrisy, religion, lots of things I hate. But the people on the left, they need to hear what’s wrong with their side and what their side is doing, and they don’t hear it on MSNBC… Every show [there] should be called, ‘You’re So Right, Chris.’” All of this is of a piece with Maher’s aversion to giving his audience what he calls “blue orgasms.”

As much as his skewering of the left might stimulate the right’s erogenous zones, Maher is no conservative ally. He remains a militant atheist, his views on religion — “Religion must die for mankind to live,” “Faith means making a virtue out of not thinking,” “Those who preach faith and enable and elevate it are intellectual slaveholders” — bluntly expressed in the 2008 documentary Religulous. For years, Maher correctly warned that Donald Trump would not give up power peacefully, and he remains outspoken about the threat Trump and his followers pose to American democracy. “The time to really be nervous about is between Election Day 2024 and Inauguration Day 2025,” he says. However annoying he finds them, Democrats “are not democracy threateners, they are not.” Al Gore accepted the Supreme Court’s verdict which ended his hopes of winning the disputed 2000 election, and “Hillary Clinton just got out her purple suit even though they were pretty sure they were going to be wearing the white one… That’s the main difference between the parties; the Democrats still believe that the idea of democracy and the idea of America are inextricably linked. One is unthinkable without the other. For the Republicans, it’s very thinkable.”

Our joints reduced almost completely to ash, I ask Maher about the role of the comedian in society. “Is it just to make people laugh?” Maher pauses to reflect. “It’s to make a lot of money, and boy am I good at it,” he says, cackling sarcastically like a cartoon villain. “The role of the comedian has always been, at best, to say the things that people are thinking and have been afraid to say, or to enunciate the things that they are saying but in a way that is very cathartic and better than they could say it… Most of comedy is a relief.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2022 World edition.