‘If we will not endure a king as a political power,’ Sen. John Sherman of Ohio said in 1890, ‘we should not endure a king over the production, transportation, and sale of any of the necessities of life.’ These words helped drive through the Sherman Anti-Trust Act that saved early American capitalism by breaking up Standard Oil and the robber barons’ fiefdoms.

A long line of Anglo-Saxon dragon slayers straggles behind the senator, all the way back to King John at Runnymede. Over-mighty kings and industrial barons get short shrift in Britain and America. This isn’t mere resentment. It is a philosophy of power and knowledge, and the principle behind democracy and free markets.

Concentrated power, political or economic, leads to the abuse of the weak by the strong. As systems cannot be fully understood or controlled from the center, knowledge must be distributed through responsive and localized voting, and a plurality of small- and medium-sized companies.

Lao Tzu, a disillusioned bureaucrat, wrote that the best systems are fluid, adaptive and particulate, like water, which ‘benefits the ten thousand things and does not contend’. Today’s politics and economics are not fluid, but frozen by political and corporate entities. Their power is detrimental to society.

Between 1996 and 2016, the number of stocks in the US halved from almost 7,300 to 3,600 — lower than the 1970s, when US GDP was a third of today’s level. In 1995, the top 100 companies accounted for 53 percent of all income from publicly traded firms; by 2015, they made 84 percent of all profits.

Four companies provide 57 percent of the poultry sold in the United States, 65 percent of the pork, and 79 percent of the beef. Six companies, mostly headquartered in New York City, now own 90 percent of the media. Britain has seen about $5 trillion of mergers and acquisitions in the past 20 years — nearly 50 percent more than in America, if we adjust for the relative size of Britain’s economy.

Oligarchies reduce productivity and wages. Between 1959 and 2001, American investment averaged 20 percent per annum of corporate revenues. Between 2002 and 2015, investment fell to 10 percent of revenue. In the Eighties, start-ups represented 13 percent of American companies. Today, they represent only 8 percent.

Once you’ve sewn up your market and outpaced the competition, there’s no need for long-term investment for the productivity gains that are the main driver of wage increases. Reducing competition for hiring also reduces upward pressure on wages. The transition from a competitive to a concentrated job market is associated with a 15 to 25 percent decline in wages. The problem isn’t a lack of jobs, but the concentration of employers relative to employees.

Corporate inequality is income inequality. A few large companies are doing incredibly well, but a host of smaller companies are barely able to meet their interest payments, let alone raise wages. The increase in corporate profit margins and the stagnation in median wages are one and the same thing. Amazon is a wonderful gift to consumers, but not to workers who might find better pay and conditions elsewhere, or to the authors, retailers, and manufacturers who sell through Amazon.

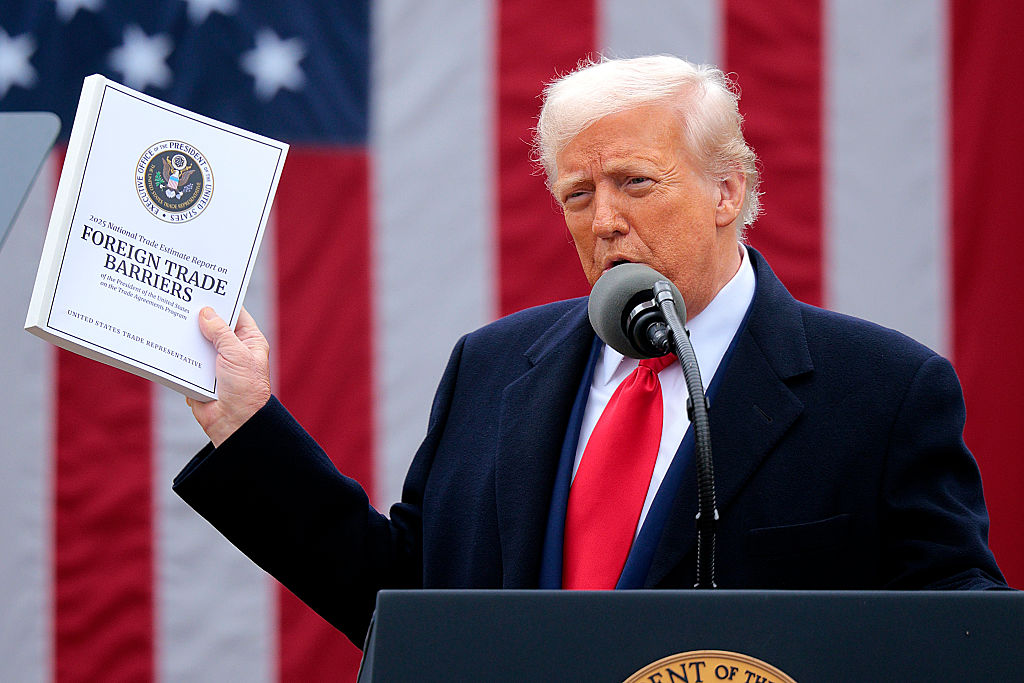

Ten years after the very banking crisis they helped precipitate, five big banks control half of America’s banking assets. The Dodd-Frank Act, the regulation intended to discipline the banks, has helped them, by hurting their smaller competitors. Dodd-Frank, Jonathan Tepper notes in The Myth of Capitalism, failed to break up America’s largest banks or prevent them from becoming ‘too big to fail’. It succeeded, however, in discouraging competition, by creating a ‘protected class of financial firms with assets above $50 billion’. No wonder a Goldman Sachs lobbyist was quoted in April 2010 as saying, ‘We are not against regulation. We’re for regulation. We partner with regulators.’

Large corporates turn any piece of legislation to their advantage. They welcome fixed costs that they will be able to meet and smaller rivals will not. They use patent protection or consumer welfare as barriers to entry. They cultivate cosy ‘advisory’ relationships with the regulators, with corporate employees frequently passing into their regulators and back again. The traffic has erased the fine line between constructive advice from industry and outright capture of government policy.

If large companies weaponize the rules, the rule should be that we don’t have large companies. This is simpler and more practicable than devising surmountable rules or trying to stop lobbying. This is a non-partisan issue. It has nothing to do with the size or role of government, only with the weight of legislation. If you believer in free markets, you will want a return to them. If you believe labor has lost out to large corporates, you will want to fragment the current power structure.

What we need is less traditional regulation and more action from the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). Lao Tsu advises that you ‘govern big countries like you cook little fish’. The CMA should block mergers where the bulk of a sector is controlled by six players or fewer, and break up sectors where this is already the case. Its recent blocking of the Sainsbury’s-Asda merger is encouraging.

Studies show that a 10 percent increase in regulatory restrictions in an industry corresponds to a 0.5 percent decrease in the number of small firms in that industry. Large firms, meanwhile, are unaffected. And the real damage is cumulative, with increasing numbers of small businesses closing after several years of regulatory growth. The poor, Tepper notes, are ‘the biggest losers’, because ‘small businesses are more common in low-income areas’.

The battles of the last few years have often been seen in terms of values: Somewheres against Nowheres, internationalists against Little Englanders, liberals against racists. The values of the EU and a multinational like Gillette may be genuinely tolerant, and many people are deeply upset that these values appear to have been rejected. There is, however, a difference between a system’s values and its effects, the concentration of political and economic power.

The poor and rural populations feel the effects first. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won 472 counties representing 64 percent of American GDP, whilst Trump won 2,584 counties representing 35 percent GDP. A similar pattern occurred in the Brexit vote. There are fewer and fewer small employers in regional and seaside towns. We may not like the messengers, but we have to respect the message.

Anyone who believes the EU’s crony capitalism is pernicious must accept that the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ systems have also allowed companies to become unhealthily big and powerful. The European Union’s power structure, lobbying culture and legislative weight have had baleful effects, but at least it has an active Competition Commission. We must revive a balanced political and legislative relationship if we are to make markets free again, and fair again.