As a longtime critic of the Clinton administration’s “free trade” agreements, I’ve lately been mocked by liberal friends who suspect I’m sympathetic to the “plan” hatched by Donald Trump and his senior advisor on trade, Peter Navarro, to “ruin” the country with indiscriminate import tariffs. This sort of jokey ridicule goes with the territory when you jab at neoliberalism from the left. Bill Clinton still has legions of fans among the Democratic party establishment and its media acolytes, and it’s hard for them to face up to the fact that the former president’s economic policies have led directly to Trump’s election as president not just once, but twice.

In 1993, in the fight to pass the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), then-president Clinton’s goal wasn’t to make the world safe for free trade – it was to raise money from those who stood to gain the most from NAFTA: the Fortune 500 companies and the Wall Street crowd that normally supported Republicans. The tactic worked for Clinton in his 1996 reelection campaign but by 2008, even cautious Barack Obama used the job losses in Ohio caused by the agreement in his campaign against Hillary Clinton. If you don’t believe NAFTA won the 2016 election for Trump, read the 2021 National Bureau of Economic Statistics study on shifting voting patterns from Democrat to Republican in counties hit by NAFTA-instigated factory closures.

I don’t like getting tagged with anything Trumpish. When my book about NAFTA was published in 2000, I found myself uneasily accepting compliments from right-wing nationalists. There were precious few pats on the back from my own kind, since in those days the “all boats rising” propaganda was just about all you would hear on television.

What I and my new right-wing pals got right was that NAFTA and the subsequent passage of trade normalization with China would wreck America’s more affluent working classes and accelerate the decline of domestic manufacturing and the destruction of not only the local factories, but also of the hometown retail stores, service businesses and schools supported by the wages and taxes paid by the owners of factories. The dollar-an-hour pay in border maquiladoras (for a 48-hour week) locked in by NAFTA’s investment protection language (and Mexico’s corrupt national labor union) was – and at less than $2 an hour still is – too good a deal to pass up for even the most risk averse, Latinophobic US factory manager.

And so the malign effects of NAFTA advanced, only to be surpassed by the wave of jobs outsourced to China, beginning with congressional approval of Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) in 2000, where cheap labor was guaranteed by Chinese Communist party repression and complemented by greater industrial sophistication and government support than was available in Mexico. Calling NAFTA and PNTR “free trade” agreements was nonsense: they were investment agreements designed to reduce costs for American business by exploiting cheap labor in foreign countries. Bringing China into the World Trade Organization was the fig leaf – China would supposedly have to behave like a “normal” country and not like a communist one that expropriated foreign businesses and disrespected private ownership.

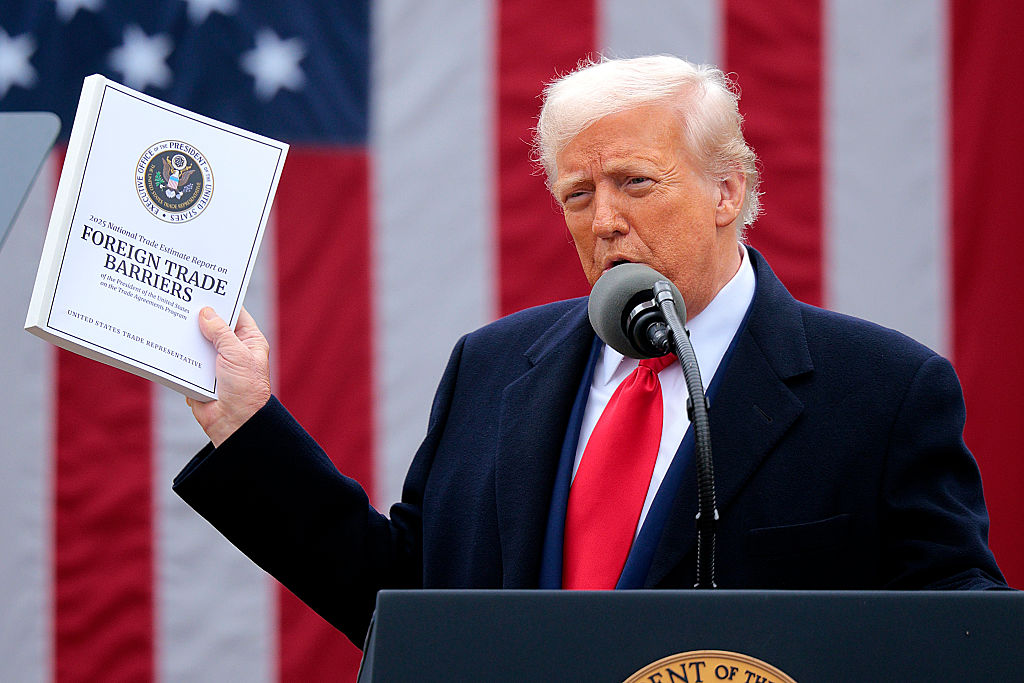

Where I differed with the right-wing nationalists, most importantly, was on the benefits of labor unions and the National Labor Relations Board. The radically anti-union industrialist Roger Milliken, for example, took what he considered a paternalistic approach toward the textile workers in his Carolina factories. But draconian tariffs weren’t much talked about by anyone in those days, since Mexican tariffs were quite low, on average, and America already had a free trade agreement with Canada (Mexico did have a 100 percent tariff on imported corn that, unfortunately for the Mexicans, was ended by NAFTA). Tariffs were for emergencies and “import surges,” but were to be used selectively, often for temporary political reasons, by Democrats and Republicans alike. Now Navarro, through his master’s voice, is absurdly trying to sledgehammer America back into industrial might even though he knows the damage done by “free trade” is too great and the difference between wages and labor laws in China and the US is too vast to be corrected by tariffs alone. Meanwhile, Trump’s corruption, ignorance and short attention span make it impossible for him to negotiate intelligently, or even to understand Navarro’s sometimes incoherent argument.

Trump, despite his attacks on NAFTA and PNTR, likes cheap labor as much as the next plutocrat. He doesn’t care about helping anybody but himself – although when Big Tech calls, he listens, as demonstrated by the tariff exceptions on China that would have affected Apple. Trump’s inauguration guest Tim Cook and his company won’t be making any iPhones in Detroit or Milwaukee for the foreseeable future.

For now, leftist, anti-Trump supporters of the American working class will have to be satisfied with small victories. Although private-sector unions have nearly disappeared in the US (thanks to Clintonomics), at least voters have heard of Shawn Fain, president of the United Auto Workers. The New York Times editorial board’s declaration – “we want to emphasize that Mr. Trump has a point about the pain caused by free trade” – is deeply gratifying to my small leftist cohort. The Times still doesn’t seem to understand that NAFTA and PNTR were designed to promote American factory and production relocations to Mexico and China, not to “open [US] doors to exports.”

Some of the alienated, formerly well-paid workers I know from Ohio and Queens don’t share my sense of ironic amusement. They say they’ll never vote Democratic again. With Trump they think they have nothing to lose and lots to gain. I respectfully disagree: Trump and his on-again, off-again tariffs are a train wreck in the making.

Nevertheless, many friends still admire Trump. For them the word “protection” means something very different than it does to an academic economist. They want to be protected, all right – from the wonders of “free trade” and the glories of globalization.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply