Flour furnishes most everyone’s kitchen. If you’re a baker or breadmaker, you will probably have several five-pound bags of it in the pantry alongside the yeast. If you don’t bake or don’t bake much, you will probably have at least a cup or two of it in the canister on the kitchen counter for thickening the gravy, frying the chicken or making the roux. Most likely, most of it will have come from wheat.

Wheat has been with mankind for 10,000 years or so and was first domesticated somewhere in the Fertile Crescent, or, as our old geographies used to say, Mesopotamia, which also, it was hinted, was the neighborhood of the Garden of Eden.

Wheat’s genetic diversity made it adaptable to a variety of climes and continents. Nowadays it comes in 25,000 varieties and is broadly classified by when it is sown. In places with milder temperatures, winter wheat (the lion’s share of the world’s production) goes into the ground in the fall and is harvested in springtime, when spring wheat is just being planted. It feels the blade in late summer or fall.

It’s possible to chew wheat for food, but it’s hard on the teeth, and the archaeologists tell us that evidence of pounding and grinding stones, which turned raw kernels into a kind of rough flour, also go back a long way and represent a primitive form of milling. The purpose — to separate the inner digestible endosperm of the wheat kernel from its outer bran and germ casing — has not changed, though milling technologies have. In the agricultural age, which made room for industrialism only in the eighteenth century and persists in many parts of the world today, the typical water-powered flour mill was everywhere. In 1870 there were 22,000 in the United States alone. They left names on the land long after the old mills vanished. Within a few miles of where I type, in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, there’s Mabry Mill, Osceola Mill, Quick’s Mill.

The industrial age took away the charm and scaled things up. Roller technology, increasingly steam-powered, came after the Civil War. It eliminated millstones but also demanded greater capital, led to industry consolidation and the demise of many small community gristmills hugging their quaint watercourses. Flour milling became big business. Efficient railroad transportation made more wheat more readily available for milling and, on the output side, made possible distribution of flour to national markets. The great milling centers moved west with America, to Cincinnati, Chicago, St. Louis and especially Minneapolis. It was a landmark moment in my boyhood summers, traveling by train from our home in the East, to behold from the dining-car at breakfast the great General Mills grain elevators at the Falls of St. Anthony as we crossed the Father of Waters from St. Paul to Minneapolis. From there on, everything was “west,” and everything was wheat.

In 1900, my father’s family settled land under the Homestead Act in the far northwestern corner of North Dakota, forty miles from Montana and five from the Canadian line. Cousins still farm the original claim, plus much more. They raise white-faced Hereford beef cattle, sometimes some hogs, but most of all they grow wheat. I called it a “wheat ranch,” to impress my pals back east. To my cousins, it was just “the farm.” Like all farmers back then, they were beholden to the weather, to their own good health and, if they were Biblically blessed, to the labor of healthy sons. My father was the youngest of five boys. And, of course, they were beholden to the market which did not always operate in their favor. The railroads set the freight rates for moving the grain east to Minneapolis, where the mill owners, often as not corporations back east, controlled the price of wheat.

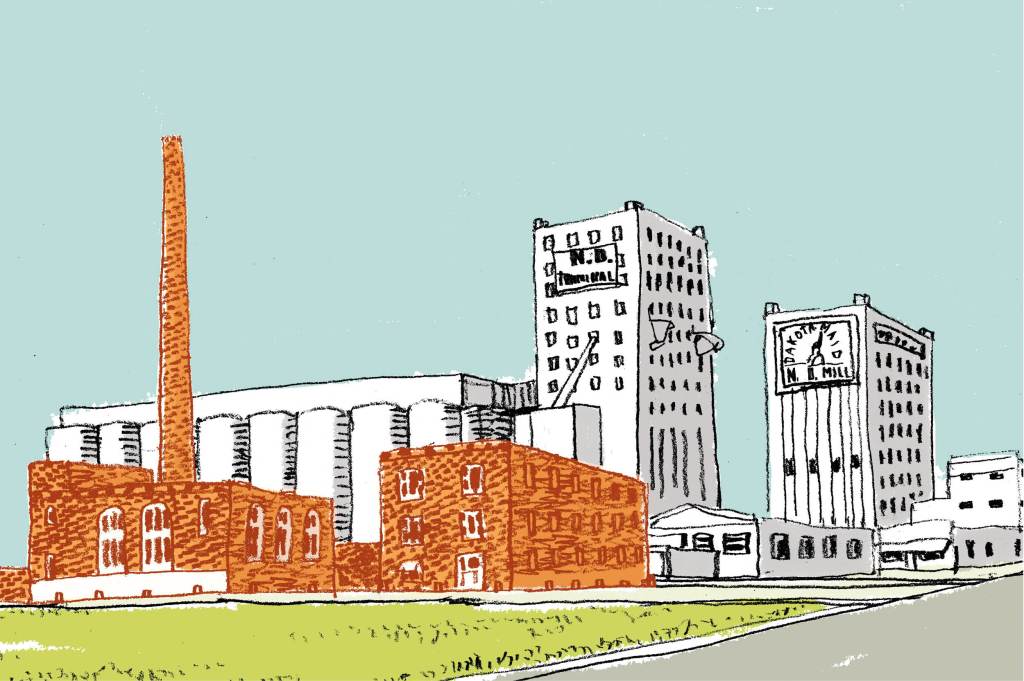

In 1919, under the auspices of the North Dakota Nonpartisan League, the farmers fought back with creation of what was and remains the only state-owned flour mill in the country. Today, the North Dakota Mill and Elevator in Grand Forks is also one of the largest flour mills in the country, milling annually 34 million bushels of spring and durum wheat, about 15 percent of North Dakota’s total crop. In a largely Republican state, it feels like an anomaly, though it has survived now for a century and turns a tidy profit back into the state treasury each year. A curious leftover from the prairie populism of the 1890s, it works for North Dakota. If only government-owned Amtrak, whose Chicago-Seattle passenger train the Empire Builder rolls by it each night, were run half so well.

My father, who was a lifelong Republican, worked at the mill during college in the early 1940s, and, though he quit the High Plains for opportunity in the East during the war, the mill left its mark. He even made, and pitched, bold plans to return after the war and establish a research company to explore new uses for North Dakota’s agricultural products. It was a romantic, young-man’s plan and never worked out. He was a chemical engineer who went to work for DuPont and stuck with it for forty years. A prairie boy with wheat in his veins and likely wheat dust in his lungs, he married an easterner who became a fine cook but was no baker. Theirs was one of those marriages built on the old-time division of labor. She made the home; he made the money. He stayed out of the kitchen except to help with the washing-up after supper (and to mix the drinks before it). Though he would sometimes talk of his mother’s breadbaking prowess, he never took the time to bake any himself, nor did he press my mother on the matter. Breadbaking would wait until the next generation, when it returned to fashion in the 1970s with the beginning of the organics movement, the Whole Earth Catalog and such domesticated hippy-ish fads. My wife would bake bread for my father. Then, long after he was gone, I would take it on myself during the late plague for something to do.

What with the diminished appetites of the elderly, we do not eat large quantities of bread anymore, and I now bake every other week or so unless there is call to give some away. These days, we are long into the age of commercial breadbaking and, urbanized and suburbanized as so many Americans are, far-removed from the sight of a field of waving wheat. Commercial suppliers leave no taste unmet, from the mass-produced “wonder bread” that nourished up the boomers in the 1950s and is still the staple with much of middle and working-class America, to the “artisanal” market for pricey loaves with hard crusts and, giving credit where credit is due, real flavor. My taste buds may have dulled with age, but between such fancy five-dollar loaves and my home-baked ones I cannot honestly tell much difference. So why bother to do it at home? The answers are commonplace: the heavenly yeast smell that fills the house, the warm feel of the dough on your hands, the illusion of wholesomeness and independence that surrounds the whole idea. If you really want to get back to basics, you will need to grind your own flour too. I know one or two bakers who aspire to.

A hundred years ago when my father was a North Dakota farm boy, his mother baked weekly a dozen or more hand-kneaded loaves (her grandson resorts to a good stand-mixer) in a coal-fired oven for her sons and husband, a working family to whom food was fuel for the body’s furnace. Her bread came not from five-pound bags of flour festooned with pizza-crust recipes and health warnings but from a 196-pound barrel stored in the unheated breezeway and delivered by rail, likely as not from one of those monopolistic mills in Minneapolis. She was not the sort of woman to speak sentimentally about her farm-wife tasks, which were all hard work. On visits to our home back east later in her life, she was much too gracious ever to complain about the Wonder Bread toast served up at breakfast and for lunchtime sandwiches. She hailed from a time and place — a homesteader’s sod hut in 1905 — that made one grateful for any bread on the table at all.

I have observed in supermarkets today a connection between the flour offerings and social class. In posher grocery stores in fancy zip codes, the sorts of places that offer twenty kinds of salt and have large stocks of organics, the flour offerings will be diverse and include plenty of non-wheat alternatives. In the wheat-flour department, by far the favored brand will be King Arthur, from an employee-owned firm in socialist Vermont. All the nice people and serious bakers I know swear by it, and it is fine flour without a doubt. Here I speculate, though not wildly: that using it, or saying you use it, delivers in addition to good bread and tasty cakes that frisson of moral superiority long associated with driving a Volvo that had been thoughtfully assem- bled by happy, unregimented Swedish workers. In more ordinary neighborhoods, you will find that supermarkets offer a narrower selection of flour but more of it. Cheaper, plain-Jane store brands predominate, along with the old industrial standards like Pillsbury and Gold Medal. Here in the South, my favorite is White Lily from Jackson, Tennessee, a flour I would stand up to King Arthur any day of the week.

And then there’s Dakota Maid, the brandname of flour from the North Dakota Mill, which used to have a Sioux Indian maid on the logo but no longer. You won’t find it retail much beyond the upper Midwest, but you can order small bags by mail direct from the Mill. It bakes with the best, and I am happy to keep it around — for sentimental reasons.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2023 World edition.