So James Bond is back, doing exactly what he always does, inviting the audience into a fantasy world for the pleasure of wondering ‘What if?’ In this respect, Bond films resemble the work of the world’s first recorded comic poet, the Athenian Aristophanes (c. 440-380 BC).

His premise was that Athens’s problems could be solved only by little people of no importance, not the greedy, vain and incompetent leaders in the public eye. So the scene was set for the hero(ine) to put them firmly in their place.

One favorite subject for his comic fantasies was the long war between Athens and Sparta (431-404 BC). Take three examples. In 421 BC Aristophanes sent a farmer Trygaeus up to heaven on a dung-beetle to find Peace and restore her to earth. No chance, says Hermes, the gods have given up on humans and buried her in a cave. Trygaeus summons help to get her out, bribing a recalcitrant Hermes with promises of sacrifices and a golden cup. Success! In 414 BC, two Athenians, fed up with life in Athens, propose a city in the air halfway between men and gods. The birds agree and Cloudcuckooland is built, cutting the gods off from the enjoyment of men’s sacrifices.

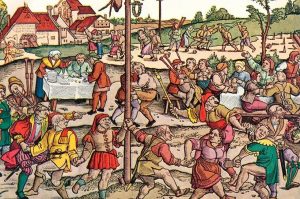

The gods treat for peace, which is also restored on earth. In 411 BC, Lysistrata launches her famous sex-strike against the war, as if there were no other sources of male sexual satisfaction in Athens. She co-opts the Spartan women, seizes the Acropolis (the state treasury) and forces the two sides to make peace.

Bond films and Aristophanes both revel in exotic mises-en-scène, and absurd plots — where they will go next is anyone’s guess — played out as if with utter seriousness by heroes on a mission, though often nudging the audience or (Aristophanes) totally undercutting the theatrical illusion and with generous helpings of comic insult and obscenity. Ah, the power and allure of fantasy!

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.