Free Time is an academic journey through two-and-half millennia of leisure options. The central question put by the historian Gary Cross, is: why do we not have more free time, and when we do, why do we waste it, like Sir Andrew Aguecheek in Twelfth Night, on “fencing, dancing and bear-baiting” or their modern equivalents?

We start with ancient Greek philosophers, including Socrates and Aristotle, who reckoned that life was all about free time. We should work to fulfil our basic needs and then use our leisure for scholé (self-improvement): for culture and reflection. The vita contemplativa was superior to the vita activa (though Socrates was also fond of a boogie — a fact Cross does not mention).

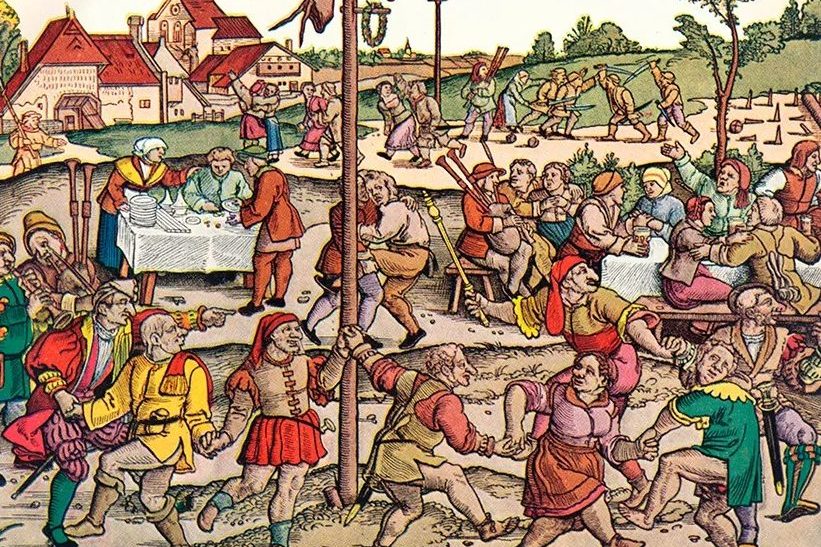

People spent their free time at festivals and religious rituals. Skip a few centuries to the Middle Ages and we find there was still a surprising amount of leisure time — bacchanals alternating, as in pagan days, with weird rites and the contemplation of God and beauty. The Reformation dealt the first blow to this tradition with its attack on the old festive culture. Puritans considered fun to be practically satanic and certainly Popish, and banned bear-baiting, theaters, maypoles, dancing, saints’ days, soccer and all types of ecstatic, carnivalesque activity. This laid the ground for the later “work ethic,” which promised salvation through toil rather than leisure. It was a convenient philosophy for the new class of greedy mill owners: it made them money.

Then drugs, Cross shows, helped the working world go round. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, sugar and tobacco were processed in appalling conditions in the colonies, to be shipped and eventually consumed in very different surroundings back home. But in England, too, children worked twelve-hour days seven days a week in the unregulated cotton mills. Then, in the 1830s, fifty years after the start of the Industrial Revolution, free time movements began springing up throughout the world. In 1835, Boston artisans demanded the “natural right to dispose of our own time in such quantities as we deem and believe to be most conducive to our happiness.” Ten years later, after many decades of campaigning by Victorians afflicted with a conscience, the British government brought in the Ten Hours Act, which reduced the working day for under-twelve-year-olds to a mere ten hours (with Sundays off).

Towards the end of the century, workers were everywhere campaigning for a further reduction of the working week. Cross cites the Boston workers at it again in a popular song from the 1880s:

We mean to make things over, we are tired of toil for naught, With but bare enough to live upon, and never an hour for thought. We want to feel the sunshine, and we want to smell the flowers. We are sure that God has will’d it, and we mean to have eight hours.

The working day was indeed reduced to eight hours in many countries by around 1920 — as a result of strikes and international campaigning by an eight million-strong Labour movement and, says Cross, a bit of Leninism. But there was another factor behind this. The management fat cats, so long resistant to a shorter working week, had finally woken up to the fact that they could make money twice over from their staff: once while they worked and again when they played. Fun began to be commercialized. The bosses exploited our inner Aguecheek.

So instead of smelling the flowers, we bought our fun from P.T. Barnum and Walt Disney. The roller coaster was invented in 1900. Clever advertising flattered wage-earners into thinking themselves free economic agents. Cars made you feel powerful. On holiday, you lived like a king. And there was endless new, improved stuff. People would never have “enough.”

By the 1930s, highbrows such as John Maynard Keynes and Bertrand Russell predicted that the working week would get even shorter. Kindly Mr. Kellogg introduced a thirty-hour week for his employees in 1932. And the following year a thirty-hour bill was passed by the Senate. But the dream would soon fade. The forty-hour week has now been the norm for more than a century, and those who hoped the masses would use their free time to attend lectures on ancient Greek poetry have been severely disappointed.

Instead, people seem to prefer money to time: to earn a lot and spend a lot on quick hits of pleasure. Reading Paradise Lost is hard work compared with riding a roller coaster. Slow and steady has lost the race. But in all this, Cross underplays the role of advertising. Google and Facebook combined now sell $420 billion-worth of ads a year. If anything like this sum was spent promoting “slow culture,” the battle against fast consumerism might be more successful.

The conclusion? Cross says he’s not “arguing for a return to a contemplative life and to the virtues of simplicity and living closer to nature.” But why not? Surely that’s the answer. Slow culture is cheap and it can be much more cheerful and rewarding than you think. Consider how popular gardening and fishing and hiking are. Slow just needs a bigger budget.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply