“They were living at le Grau du Roi then and the hotel was on a canal that ran from the walled city of Aigues Mortes straight down to the sea.” So begins Hemingway’s posthumously published transgender-themed novel The Garden of Eden. He began writing it in 1946 and kept at it intermittently through his long mental and physical decline. Yet it’s a marvelous novel, in parts as vivid as Hemingway’s miraculous early stuff, which, once read, susceptible people confuse with their own lived experience.

In 1927 Hemingway and his second wife Pauline came to Grau-du-Roi on the Camargue coast for their honeymoon and the first three chapters of the novel are clearly based on that visit. As one of the susceptibles, I was very interested to see the canal, the lighthouse, the jetty, the beach and the hotel, and to experience the light and the wind, and to compare them with the indelible images and feelings planted in my head by a barmy old drunk clinging to the wreckage of his once-great artistry.

He and Pauline stayed at the Hotel Bellevue d’Angleterre, an imposing old building on the canal at the heart of the fishing port. But two stars and some angry reviews put us off there and instead we chose the Hotel Café Miramar, a modern family hotel and restaurant further down the beach. We had a second-floor room with a sun-trap balcony and wide sea-view. From here it was a short walk back along the water’s edge to the working port where the novel opens and we are introduced to the two young lovers, who are at it like a honeymoon couple in The Benny Hill Show.

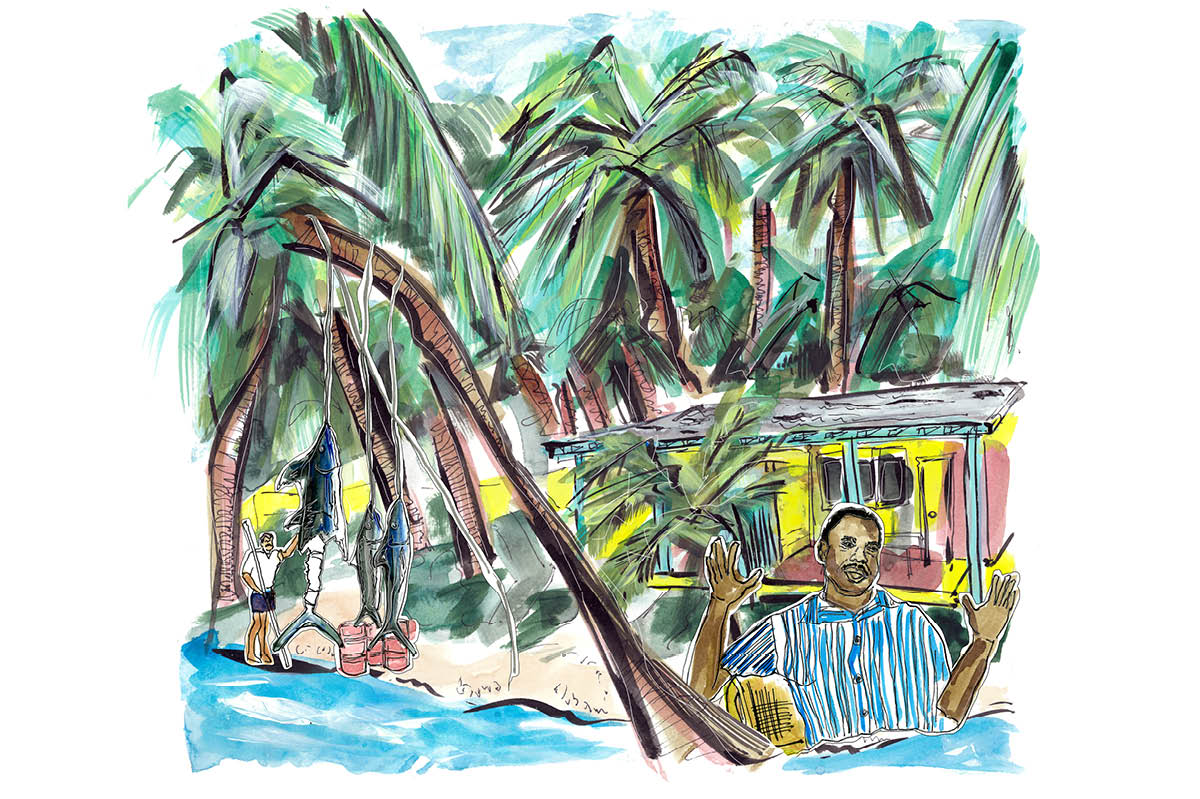

“It was late in the spring,” intones the exhausted narrator, “and the mackerel were running and fishing people of the port were very busy.” It was late spring for us too and we also found the fishing people of the port very busy. Trailing flocks of screaming gulls, the fishing boats came in from the open sea and chugged up the canal. One tied up opposite the Hotel Bellevue d’Angleterre and we stayed to watch the crew unload the catch. The faces and arms were burned nearly black by the sun and wind and they shouted as they flung the empty plastic crates around and heaved the silvery fish-filled ones up and over the side.

Then we walked further on up the white jetty to watch other boats steaming in and Catriona put up her red umbrella and stayed well back from the edge in case she was attacked or shat on by an overexcited gull. The violent wind and dazzling light and the maddened seagulls and the vastness of the sea and sky had a hallucinatory quality that made us feel friendly, cheerful and meditative all at the same time while we stayed at Grau-du-Roi.

As it is a Hemingway novel, the narrator casts a line from the jetty one morning and immediately hooks a monster sea bass. The fish is too strong to land alone so he plays and walks it along the jetty and into the canal and through the town as a throng of excited townsfolk gather to cheer and clap him on the back. Upstairs in the hotel his wife glances out of the window and is pleased but perhaps not surprised to see that her new husband is the town’s new fisher king. The sea bass is the largest caught on a hand line that anyone in the town can remember. It’s too big a trophy to be cut up, so it is packed in ice and sent away, maybe to a Paris restaurant. “Or maybe somebody very rich will buy him.” This last because Hemingway is back on his usual carp about his natural talent being corrupted by the predatory wealthy.

So for his dinner he settles for a representative, plate-sized sea bass.

“The bass was grilled and the grill marks showed on the silver skin and the butter melted on the hot plate. There was sliced lemon to press on the bass and fresh bread from the bakery and the wine cooled their tongues of the heat of the fried potatoes.”

Catriona and I walked back to our hotel restaurant terrace for supper and were shown to a table lit by the last rays of the sun. At the next table the sun-blackened crew from the fishing boat that we’d watched unload were eating oysters and razor clams. At a farther table was a party of four silly drunk adults and a sober child who talked to the drunk adults respectfully as though they weren’t drunk at all.

We chose the sea bass. It was grilled and the grill marks showed on the silver skin and so on and so forth. Exactly the same. The sliced lemon, the fresh bread, the wine. Except the potatoes were mashed instead of fried.

And it was good.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2022 World edition.