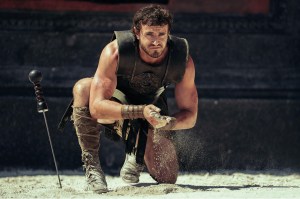

There are heroes and then there are unsung ones — and I basically prefer the latter as I have known a few of them in my lifetime. The funny thing is that I grew up learning only about famous heroes, the Ancient Greek type, starting with the semi-god Achilles. Homer didn’t deal with unsung heroes; everyone was larger than life, and there were only winners and losers. The person I’ll tell you about this week would not have been a Homeric hero, but he certainly was one while participating in the most dangerous game in the world.

Lance Macklin was an Old Etonian, a World War Two navy vet, and a dashing racing driver at a time when a shunt meant instant immolation and certain death. Just off the top of my head I find a few names of young top drivers that were lost while racing before the sport became safer than soccer or volleyball: Ascari, Castellotti, Levegh, Musso, von Trips, Behra, Collins, Bonnier, Portago, Bandini, Clark, Scarfiotti, Courage, Cevert and hundreds more who died in the golden age of motor sport during the 1950s and 1960s. (Only four great ones survived: Stirling Moss, Jackie Stewart, Jack Brabham and Graham Hill.) The tragic dimension, coupled with speed, adventure and youth, made motor sport a natural follow-up to the flying heroics of the war.

Jack Barlow is a Kiwi, New Zealanders being among the people I like the best, but he’s also a very good writer and has captured the mood of the times. Why and how he chose to write about Lance Macklin I do not know, but he’s done a heck of a job, and none of the dialogue that takes place in the story is made up. It all comes from contemporary accounts and interviews. And I should know, as Lance was my uncle-in-law. I was married to his niece, Cristina de Caraman, the most beautiful of all young girls in Paris back in the early 1960s, so pretty in fact, that Paris Match put her on the cover under the heading “C’est une deb.”

Needless to say, the marriage did not last long. We were both living an F. Scott Fitzgerald life, going out every night, and I was always chasing you-know-what. Yet Cristina and I have remained good friends all these years, and when she rang me recently from Palm Beach just to say hi, I told her that I was writing about her Uncle Lance. He had a sort of sad ending in a retirement home, something people like myself do not understand. But it’s an Anglo-Saxon perversion, so I’ll leave it at that. Now back to racing and his part in the greatest tragedy of the track.

The title of Jack Barlow’s book is A Race with Infamy: The Lance Macklin Story. It is called that because, on June 11, 1955, Lance was a central player in motor racing’s worst tragedy. More than eighty spectators were killed and I believe hundreds were injured when the Mercedes of Pierre Levegh went flying at 150 mph into the Le Mans crowd after coming into contact with Macklin’s Austin Healey, which had swerved to avoid the Jaguar of Mike Hawthorn. I will not go into details, but Lance got the blame for a Mike Hawthorn mistake. Hawthorn was the eventual winner of the twenty-four-hour race. The book deals with the tragedy in detail and fairly. That day, needless to say, overshadowed Lance Macklin’s remarkable career as one of Britain’s leading and fastest drivers.

I got to know Lance well during my brief marriage to his niece. He had two beautiful sisters — Nada, who married a French duke and was my mother-in-law for a couple of years or so, and Mia, who married a very rich American aristo, but got bored with him and left asking for nothing.

Lance was known among the racing community for being very, very fast. He and Stirling Moss were close friends, and when not competing against each other they were nonstop chasing the W: women. Both were girl-crazy and both were much married and so on. Both were, for obvious reasons, very, very good men. Lance could have written a book of “raw, unflinching honesty” like Harry the halfwit apparently has, but back then gents didn’t resort to such tactics. Enhancing one’s celebrity with a book was not on.

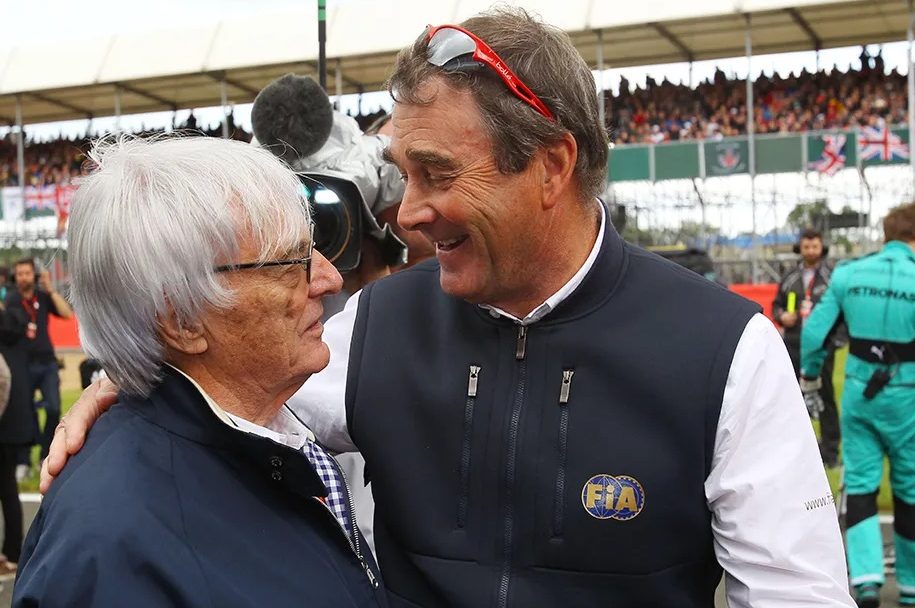

Along with many other things, dashing, death-defying racing drivers are no more, and the present bunch resemble robots. Now the fastest car wins no matter who drives it, whereas in the past it was the driver who dominated, not the machine. My friend Taffy von Trips, in an inferior Ferrari, tried to pass the great Jim Clark in the Monza Grand Prix of 1961 and died in a fiery crash. I went to his funeral in his family castle near the Black Forest and it was heartbreaking. Alas, I was also present when Lorenzo Bandini died at the chicane at Monte Carlo.

Never mind. As they say, it’s all in the past. Except that the book brought back wonderful memories of fearless young men facing death every Sunday after getting drunk at the Tip Top in Monaco the night before. I remember seeing Mike Hawthorn and Peter Collins doing just that, and then racing all day Sunday, Hawthorn in his green jacket and bow tie. Collins died in Germany a month later. Hawthorn won the championship and died in a road accident that winter. No sad or flailing years for them.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2023 World edition.