Formula One is having a moment. Its global popularity is soaring off the back of a wildly successful Netflix docuseries, Drive to Survive, and the launch of glitzy races in Miami and Las Vegas. It is even drawing attention away from other sports. The most significant move of European soccer’s January transfer window was Lewis Hamilton’s announcement that he is off to Ferrari next year. A pivot towards entertainment has created a new generation of fans. But will it come at the expense of the racing itself?

The Formula, by Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg of the Wall Street Journal, immediately establishes that Formula One is all about rules. It is governed less by an administrative body than by its dense rule book that seeks to determine precisely what designers can and can’t do with their cars. Competitive advantage lies in finding a loophole within the rules. This, the authors argue, is much more consequential than hiring the best driver. The most skilled racer might be two-tenths of a second a lap faster than the rest of the grid; a loophole could be worth many times more.

Some loopholes are technological. In 1992, the Williams car of the British driver Nigel Mansell contained a paperback-sized computer that could make real-time adjustments to the suspension as the car sped round the track. Mansell won that year’s drivers’ championship, as did his successor, Alain Prost, in 1993. There was nothing in the rules about computers as no one had ever thought about them.

Others are strategic. In the late 1990s the tyre manufacturer Michelin announced it would re-enter Formula One to compete with the Japanese company Bridgestone, whose products had been criticized. All of the teams duly switched to Michelin except for Ferrari, which spied an opportunity. Ferrari co-opted Bridgestone to design tires specifically for its drivers. “It was like a bespoke suit from Savile Row, while the rest of the grid wore off-the-rack,” say the authors. The sport’s “natural equilibrium” is to have a single team in possession of the latest advantage and the rest of the pit-lane struggling to catch up, risking dull races that put off viewers and sponsors. In both the Williams and Ferrari cases, the governing body, the FIA, banned their innovations.

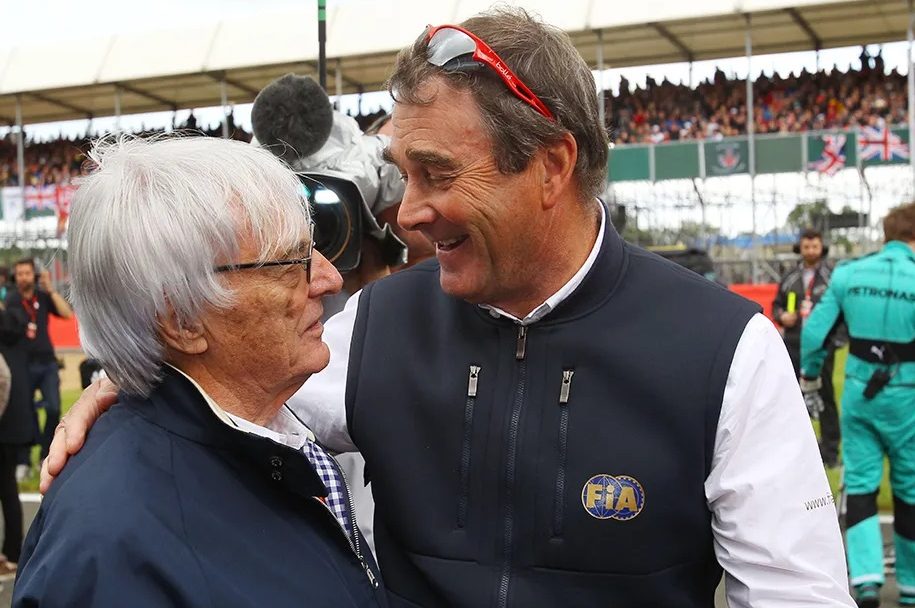

It takes chutzpah to design a car with a secret computer or, in the case of Renault in 2008, instruct a driver to deliberately crash his car to enable his teammate to win. Formula One appears to have attracted more than its fair share of individuals willing to go to extraordinary lengths to win, perhaps reflecting the man who spent forty years at its head: the British entrepreneur Bernie Ecclestone.

More than anyone, Ecclestone knew the value of occupying the gray areas. It was he who noticed that teams were leaving a lot of money on the table by negotiating fees with the circuits individually. He persuaded them to let him organize the whole shebang, to take on all the risk for a small slice of the revenue. Immediately, he drove up the fees that circuits had to pay. His willingness to take Formula One anywhere, including apartheid-era South Africa and junta-controlled Argentina, meant he was never short of leverage.

He had his blind spots. He failed to make inroads into the US and gave up trying. He was dismissive of young fans (they “don’t buy Rolexes”) and digital media (he sent Hamilton cease-and-desist letters whenever he posted racing content on his social networks). Nevertheless, Ecclestone did such a successful job in enmeshing himself within Formula One that when he sold his entities to a private equity firm, CVC, they kept him on as CEO.

Ecclestone and CVC grew Formula One from a primarily European concern to a global roadshow. But its current buzz began only after CVC sold up to a US conglomerate, Liberty Media, in 2016. The newest owners insisted that the teams stop thinking of themselves as bitter rivals, like European soccer teams, and more as business partners paid to compete, like NFL sides. It also believed that Formula One needed to change its image: less old-world, off-limits Ferrari, and more in-your-face Red Bull. Letting in the Netflix cameras was a masterstroke. “No one had expected the highly secretive world of F1 to be so candid,” say the authors.

Robinson and Clegg are also likely recipients of this new spirit of openness. The Formula benefits from excellent access to the key players — a challenge for many sportswriters. There are a lot of fun anecdotes, as well as a sharp eye for detail. Their research told them of the former McLaren supremo Ron Dennis’s love of tidiness and hygiene; so they noticed that when his disgruntled driver Fernando Alonso chose to eat a dribbly peach with his fingers at a media briefing it was designed as a subtle dig at his boss. The book frequently finds the humor and absurdity in a sport that has always been about excess.

Inevitably, the authors end on the most infamous race of the modern age: Abu Dhabi, 2021. The two world championship contenders, Hamilton and Max Verstappen, arrived at the final race of the season dead-level on points. Hamilton was cruising to victory until a straggler crashed, bringing out the safety car. Verstappen immediately put on fresh tires. Hamilton was nonplussed; the regulations should have seen the drivers maintain their positions behind the safety car until the end of the race. Inexplicably, the race director, Michael Masi, brought the car in early, setting up a final-lap sprint. Verstappen passed his rival for glory. Hamilton was incensed. The race caused a sensation. Masi has never explained his decision, but it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that his chosen ending generated more engagement than a safety-car procession.

Robinson and Clegg suggest that Liberty-era Formula One has edged towards becoming a “post-sport sport.” Its new supporters will binge-watch Drive to Survive and follow a paddock of drivers on Instagram but might never watch a Grand Prix. Does that matter? Tradition would say yes. But the rules governing Formula One have always been more flexible than they appeared.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazines. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply