Joy’s Toasted Parmesan Canapés: mix four tablespoons grated Parmesan cheese with half a cup of grated Swiss (or any other mild cheese that will melt), add mayonnaise enough to make a spread, season with salt and oregano or basil, spread on bite-sized rounds or squares of thin-sliced white bread, top with a slice of green olive (optional), broil until bubbly, serve immediately.

Caveat, sophisticates: the ‘Parmesan’ likely as not was that pale yellow powder dispensed from the green Kraft cylinder, the Swiss was from Wisconsin, the mayonnaise was aka Miracle Whip Salad Dressing, the spices dried ones from the McCormick jar and the bread courtesy of Pepperidge Farm (if you were lucky). Not a whiff of anything cordon bleu or ‘artisanal’ here, the latter a term not yet dreamt-up c. 1960. The result however— if you watched the broiler like a hawk and didn’t let them burn — was tantalizing. Accompanied with a dry martini, extremely so.

The source of this recipe, and thousands of similar ilk, traces to a genre of cookbook that gets a bad rap, if indeed it gets any notice at all. I will put a name to it — ‘Ladies’ Charity Cooking’ — and will wager that somewhere on your own shelf sits an example or two, probably little-consulted anymore yet glossed with memorable marginalia: ‘Try’, or ‘Like Mamma’s’, or ‘With Gary’, a departed friend with whom a favorite dish once was shared, or just ‘Excellent’ and a date. ‘Ladies’ Charity Cooking’ may sound as if it belongs to another age, and it does. But old books, we need to remind ourselves, are often good books, and some of these are too. On my shelf, I count a dozen or so, mostly from the 1950s and 1960s, which was their heyday. More recent examples have changed little from the spirit of the originals, the biggest distinction being the disappearance of the once nearly-universal ‘Mrs’ before the names of contributors.

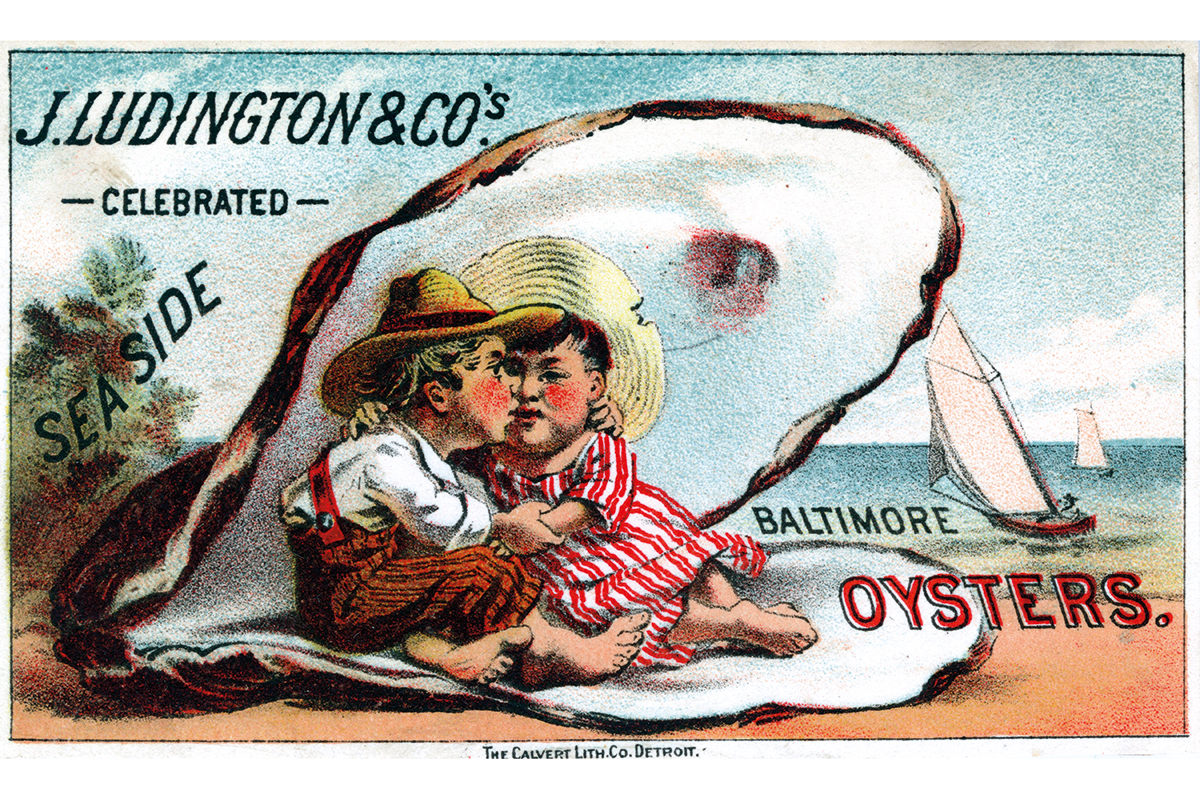

These are not published works, but sponsored printed ones. The artwork tends to be homey line drawings. There is no snazzy food photography. The intended audience reaches little beyond their own contributors and the church-, club-, family-communities they belong to. Such audiences, though, renew themselves over the years, turning the hoped-for ‘profitable project’ into the evergreen fundraiser. Reprintings are common. From my collection: Recipes from Pawleys Island (the Women’s Auxiliary of All Saints Church, Waccamaw, South Carolina); The Cotton Country Collection (the Junior Charity League of Monroe, Louisiana); Frontier Favorites (the Niagara Falls Service League, Niagara Falls, New York); The Gunston Hall Cookbook (the Regents of Gunston Hall, home of George Mason,‘Father of the Bill of Rights’); Blossom Seasons (the Women’s Committee of The Cleveland Orchestra); Bone Appétit (the Virginia Beach Orthopedic Associates). Each has a unique, yet universal, flavor.

Who were these cooks and compilers? They belonged, let us just come out and say it, to a class of American women clearly identifiable in the period between the 1940s and the 1970s, that is, before the feminist movement utterly reordered the country’s domestic landscape. Middle-class, sometimes even upper-middle-class, they were wives, mothers and homemakers. This was still the age when a single salary (or, further down the scale, even single wage) was enough to provide for a family. The husbands, who earned it, were the doctors, lawyers, managers, engineers and all manner of corporate men in white shirts and, if not literally gray flannel suits, then always, at work, jackets and ties. Tasty meal preparation and home entertaining were a part of the busy homemaker’s responsibility. Some resented this arrangement as constraining and unjust; others did not but carved out in their kitchens domains where husbands feared to tread unless it was on the way to the liquor cabinet. None of the recipes in these books is by a man.

Americans in those days ate and partied largely at home, and the range of dishes that supplied them was enormous. These were homes, it should also be noted, from which since World War Two domestic ‘help’ beyond the weekly cleaning lady had largely vanished. Mrs Jones and Mrs Smith did it all. Thus, themes of speed, ease of preparation and, yes, economy. The goal was a reliable end product that tasted right, and the same, every time. It had nothing to do with the ‘experience’ of cooking itself: the assembly of fine fresh ingredients, skill with a boning knife, finesse at whisking a complex sauce.

It is easy, from our post-Julia Child/Alice Waters perch, to snigger at the frequency, for instance, with which one encounters canned and frozen ingredients in these recipes. Recall, however, that canned and particularly frozen ingredients actually opened up the range of tastes available to domestic cooks, before the age of megamarkets stocked from around the world and expensive farmers’ markets trendily touting ‘local’ and open just on Saturday mornings. The writer, whose mother was one of these homemaker-cook-entertainers from seventy years ago (who later taught herself French cooking and to her dying day remained fluent in both kitchen languages), recalls a childhood larder with plenty of fresh meat and poultry and neat boxes of Birds-Eye frozen vegetables.

The result was cooking — not ‘cuisine’ — that was unpretentious and could taste remarkably good to palates of the time. It was also straight-up American, any nods to ethnicity going not much beyond creole, stroganoff and Kiev. But then, what would one expect from a historical moment when America was on top of the world, when not just our cars but our fridges and freezers were twice the size of anyone else’s, when kitchen counters were filling up with whiz-bang push-button labor-saving devices?

Recall too that not many middle-class Americans had yet traveled abroad to discover olive oil and good wine. Sure, you might know a couple of German or Italian dishes if your grandmother came from the old country, but that was memory at work, not aspiration to something else, culturally superior, that you needed to measure up to. The age of ingredient-obsessed foodie-snobbery was not yet upon us.

The Ladies’ Charity Cookbooks are neglected historical artifacts. They tell us how America tasted, then. And to most of those who sat down to such cooking, then, it tasted good. Before we sneer, moreover, at the frozen veggies and canned soup and protest —’Oh, how unhealthy!’ — remember this. These were recipes that produced, by the accepted democratic standard of the day, ‘fresh’ food, cooked-to-order, at home, one mealtime at a time and then repeated endlessly over and over again: no mean feat. Such cooking was ubiquitous in mid-century middle-class America, and as far as I can tell it nourished the nation reasonably well. Along with many others who were raised on it, I have since developed other tastes and techniques. Some of these too, will seem equally laughable in another 50 years’ time.

There are two ways, for instance, to view today’s tendency to outsource meal preparation to the ‘prepared’ cornucopia from your local Wegmans or Whole Foods. If variety is the thing, what an embarrassment of riches. Or have we merely addicted ourselves to a lot of expensive (and thus high-margin for the vendor) leftovers reheated at home? What’s ‘fresh’ anyway? Or consider our kitchens, which have gotten ever grander even as the time we spend cooking in them declines. Ask a real day-to-day cook which they prefer: the cluttered but efficient galley, where it’s a couple of steps from pantry to sink to chop-top to cooktop, or a ‘magazine’ extravaganza made more for socializing?

Ship-and-Shore Casserole. Round Steak Hot Dish. Yum Yum Salad. Chicken Ambassador. Tomato Surprise. Mushroom Supreme. Aunt Mimi’s Cream Cheese Braids. Sylvia’s Swedish Meatballs. Who says America’s menu wasn’t ‘diverse’ in those days? This was food for a practical people who liked to eat. Food was a necessary part of living, which meant cooking was too. Remember too that all these Ladies’ artifacts beg use. So set aside, for an evening, all your latter-day culinary sophistication and give something a try. I shall make it a dare: if you will, I will.

If Joy’s Canapés won’t quite fill the hole, then perhaps something more elemental, like this from Mrs J.M. Powell Jr. of Waccamaw Parish, will hit the spot:

Pork Chops: trim fat off eight to 10 center cut pork chops, salt and pepper. Place in a casserole dish. Pour one can cream of mushroom soup and one can of water. Bake in 400-degree oven for an hour or until done. Gravy is delicious served on red rice or mashed potatoes.

Who’s to argue?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2021 World edition.