This year marks the forty-fifth anniversary of Arvo Pärt’s Fratres — one of a series of groundbreaking compositions that Pärt wrote between 1976 and 1978 using his tintinnabuli style. Most of Pärt’s works in this compositional style, which means “little bells,” are in two voices — usually one a triad and the other a melody — which are played in such a way as to create an underlying drone. This creates a piece of music that is both concrete (single notes ring out clearly) and ephemeral. We see this in pieces like Für Alina (1976), Fratres (1977) and Spiegel im Spiegel (1978).

Pärt was born in Estonia and grew up in the Soviet Union, but was influenced by twelve-tone serialists like Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen. However, he became dissatisfied with the flatness of atonal music and stopped writing in 1968. He didn’t compose anything for eight years, other than his Symphony No. 3. He finally broke his silence with Für Alina, which is considered his first tintinnabuli composition, followed shortly afterwards by Fratres.

To listen to Stockhausen’s serial Klavierstücke V, Work No. 4, for example, or Boulez’s Piano Sonata No. 3, and then listen to Pärt’s Fratres is to experience something of the freedom Pärt likely felt in escaping the atonal prison house.

Atonal music is anti-hierarchical. It is supposed to give each note its full presence by not linking it to a tonal center. What’s striking is how completely atonal music fails to do this. The notes of Webern’s Variations, Op. 27, for example, are flat and forgettable. Their independence from a complex structure, where they have no discernible melodic relationship to the other notes in the composition, does not give them a presence. It erases it.

But the opposite is the case in Pärt’s Fratres. It is in A minor. The melodies and movement encourage attention to the individual notes. In fact, more than any modern composer I’m aware of, Pärt’s music rewards attempts to hear each individual note. (I recommend listening to Pärt with a Bourbon neat, turning off the lights, and cranking up the stereo so you can concentrate on each note and feel the movement of the piece.)

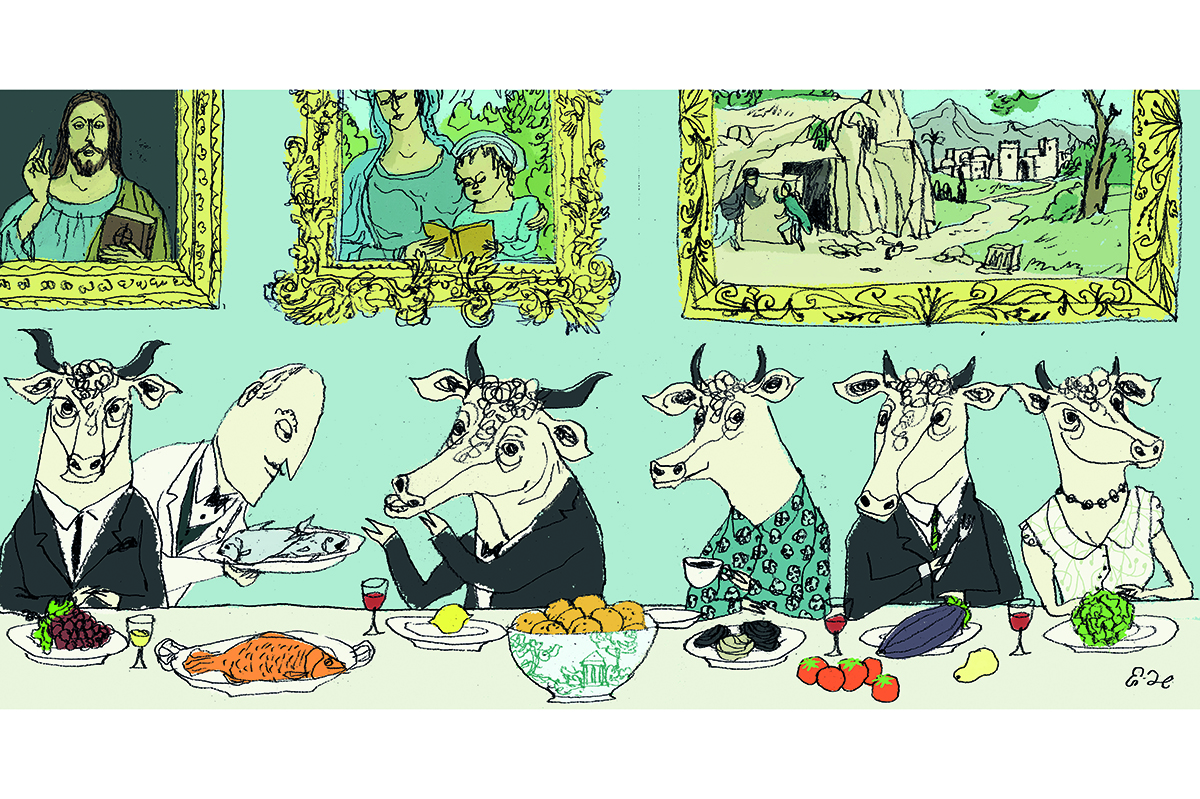

Pärt accomplishes this not by abandoning hierarchy but by acknowledging its inescapability. It is impossible to create a purely egalitarian work of art. Something must always structure the work. Without that something, there is no work at all. Supposedly egalitarian works are always ugly because they are attempts to create a work of art against the very principles of art.

Pärt converted to the Orthodox church sometime before Fratres, and his work expresses his view that in life “sorrow and consolation, brokenness and wholeness” are intertwined, as Peter C. Bouteneff puts it in his excellent Arvo Pärt: Out of Silence. Pärt’s Adam’s Lament, based on a text of Saint Silouan of Mount Athos, captures the Christian’s “state of sober, watchful mourning, unshakably faithful in God’s love, Christ’s self-emptying victory,” Bouteneff writes. This is what the faithful are supposed to practice with greater attention during Lent.

But Pärt’s music is much broader than this. It also captures how life is marked by periods of happiness and unexpected sadness, how “there is no joy not tinged with grief,” as Bouteneff puts it. Whatever your religious beliefs, the honesty of Arvo Pärt’s music is a balm for the soul.

Start with Fratres for violin and piano, then listen to Spiegel im Spiegel, then Triodion (with the words), Bogoróditse Djévo, I Am the True Vine, and Magnificat. If you have a solid afternoon free — maybe on a Sunday — give Pärt’s Passio a try. It’s not for everybody, and I think Pärt is best with works that come in between ten and twenty minutes. Passio is over an hour, and Pärt’s compositional style is difficult to sustain in an interesting way for that long, but the piece has grown on me over the years. I also highly recommend Adam’s Lament and his wonderful My Heart Is in the Highlands set to Robert Burns’s poem. (I prefer David James’s 2000 performance to Else Torp’s, but both are excellent.)

If you want to watch a documentary on Pärt, watch 24 Preludes for a Fugue. This version has English subtitles, and it is better than That Pärt Feeling.

Give Pärt a try.