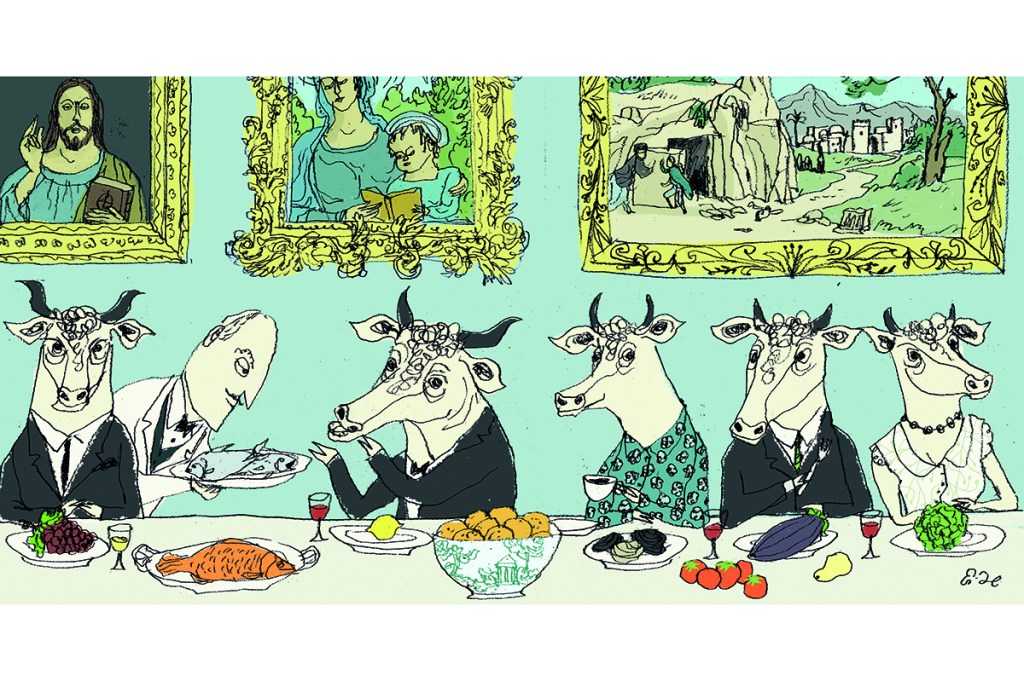

Lent is upon us, and it is once again time to meditate on the unusually self-aware admission of Sir Andrew in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night: “I am a great eater of beef, and I believe that does harm to my wit.”

It has until now been an exceptionally good season for beef. Grass-fed meat from organic Belgian Blues has featured perhaps the best steak this writer has experienced, except for one time in a restaurant with a yellow-painted cinderblock exterior somewhere off the shoulder of a Burgundian route départementale. Paper-thin sheets of Wagyu rolled into ridiculously expensive appetizers have not been lacking. Beef Wellington encased in exquisitely gilded pastry and homemade liver pâté has been as glorious as a new Waterloo (though unlike its eponymous duke, it did not survive the fork-fraught champs d’honneur). Both prime rib and shepherd’s pie have graced the board, and more than once have the delightful aromas of steak and kidney pie wafted through the kitchen.

But now, no more beef, or at least significantly less. This is no time for fond regrets or idle recriminations. Forward, fellow fasters — ours is not to reason why, ours is but to fast and die (to ourselves, that is). Into the valley of Lent ride the six hundred.

Lenten abstinence from beef (and other flesh meat) makes you holier for much the same reason it might make you wittier: It’s all about detachment from the things that tie you down to the purely material. The idea is to gain perspective through small inconveniences, such as giving up meat on Friday. This serves as a concrete acknowledgment that the individual aims to adapt to God’s preferences, even in humbling and seemingly unimportant matters like what to have for lunch.

Does God even care what we have for lunch? Well, of course — why else did He bother to create twenty kinds of edible mushroom, not to mention arugula, walnuts and gorgonzola with which to stuff them? The world, admits the faster, isn’t my oyster — it’s God’s oyster, though even in Lent He doesn’t object to us wading into a plate of the delicious little mollusks with glee and a glass of Pouilly-Fumé, as long as the spirit of moderation is observed (yes, I know, a big if).

In truth, Lenten rules are far from severe for Catholics in our era. On only two days, Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, are we obliged to cut out meat and reduce other edibles to a maximum of one full meal and two snacks. On Fridays in Lent, fasting isn’t required but meat is out. That’s all the law requires.

Hardly the stuff of St. Simeon the Stylite. And in some circles the clergy aren’t shy about pointing this out. Do you want to be a mere letter-of-the-law-ish Catholic, they ask? Do you want to be a box-ticking, do-the-bare-minimum, pale, sad, spaghetti-spined, wimpy Catholic who rolls over and waves four paws in the air every time a creature comfort comes within fifty feet? No? Then you should strongly consider — provided you aren’t a coal miner or a nursing mother — going a bit further, for instance, skipping all meat Wednesdays and Fridays, and reducing the daily dining schedule to one full meal plus two meatless mini-portions. (Sundays are technically feast days, by the way, and don’t count.) Oh, and giving up chocolate (or sugar in your coffee, or whatever other minor penance you see fit to adopt). St. Simeon would still be unimpressed, but at least he wouldn’t weep great salt tears and don an extra hair shirt. I think.

The hardest part about all this is remembering to do it. This is why in some circles the above-and-beyond version of Lenten fasting has become something of a Tough Mudder challenge. Pros share best practices, like drinking saltwater to replenish electrolytes and working to reduce one’s “eating window.” Celebrity intermittent-fasting techniques are hot discussion topics. Additional food groups are dragged up for scrutiny. Seafood, some contend, is more luxurious than meat, so shouldn’t we be giving up that too and sticking with pasta, beans and rice for the duration? Should we really take Sundays off? And who can honestly reconcile drinking alcoholic beverages with the penitential spirit of Lent? (I can answer that one: monks. Legend has it that Paulaner beer was first brewed as a nutritious Lenten beverage by German monks on a far stricter regime than any we’re familiar with, so there.)

The great thing about being a Catholic is that you don’t have to reinvent the wheel and go for the most heroic penance all the time. You can go above and beyond, of course, if you want to, but part of the point (or so I contend) is complying cheerfully with the small things that are asked — being humble and accepting the mild and inglorious discomforts they impose, such as headaches and short-temperedness, rather than accomplishing a self-assigned Twelve Labors of Hercules. While a shift toward simplicity of diet certainly seems in the spirit of the thing, what about gravitating toward frozen tilapia in the supermarket rather than the live lobster or the Arctic char?

And there’s something to be said for the spiritual peace and order brought by adhering to a prescribed schedule of moderate yet balanced meals, featuring a reasonable range of protein-rich foods. So many of us today are busy, overcommitted, always rushing — couldn’t the case be made that the self-discipline of a simple but consistent schedule is an offering potentially on par with the generous desire to do something magnificent and self-sacrificing for God?

But don’t listen to me. I’m only putting in a weak claim for moderation because the prospect of a fast day gives me a headache and puts me out of temper. My blood sugar levels rise up in fury at the idea of more than one meatless day per week, and blanch at the picture of skipping breakfast. The thought of religious orders who give up meat permanently, like the Carmelites, has me partly terrified, partly fascinated. But mostly terrified. So what do I know? My resolution for Lent this year was going to be listening to Beethoven’s late quartets (austere and meditative, I’d argue) while rereading Shakespeare’s sonnets. No, really; at least one of them is quite sobering, “Poor soul, the center of my sinful earth…”

Poor soul indeed. I think I’m due for a sermon about box-ticking spaghetti-spined Catholics any time now, upon which I’ll hang my head and admit the truth: I am a great eater of beef, and it does harm to my wit.

It’s going to be an emotional time. Please don’t try talking to me until Easter.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.