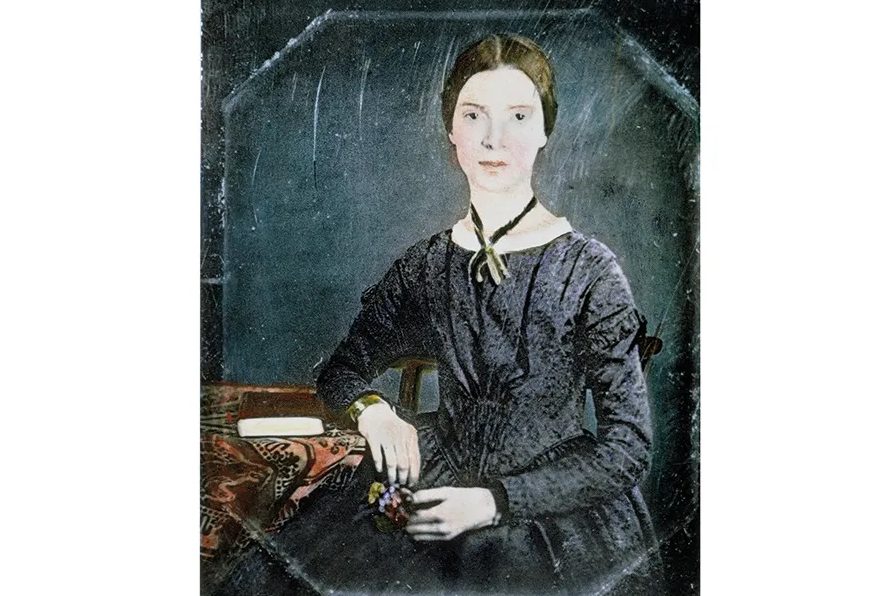

Writers have all sorts of hobbies. Tolstoy liked to play chess. Dostoevsky, as everyone knows, loved to gamble. Nabokov collected butterflies; Hemingway, wives. Eugene O’Neill’s favorite pastime was drinking. Flannery O’Connor, of course, loved birds. Emily Dickinson loved to bake.

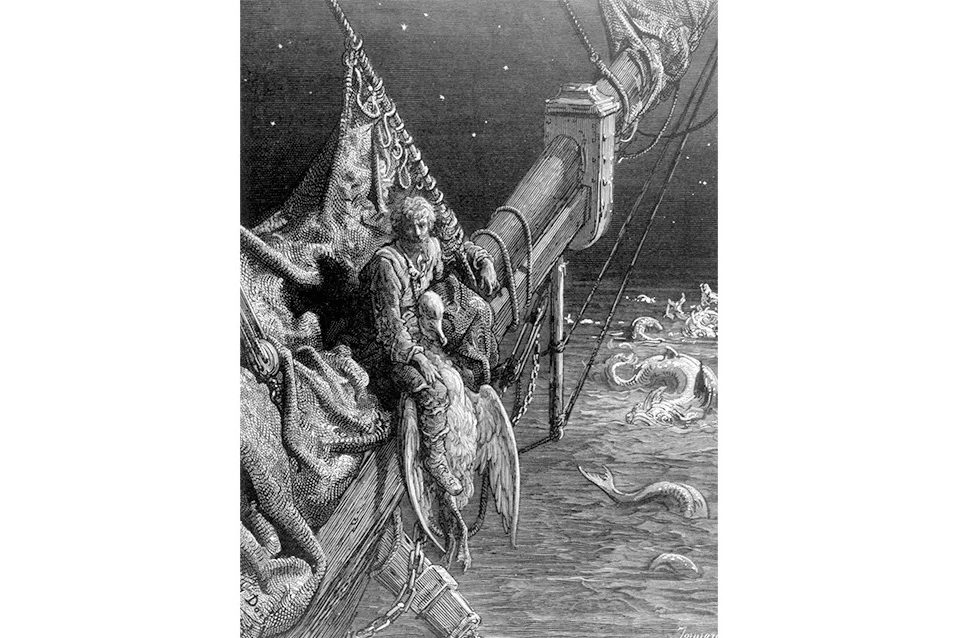

T.S. Eliot was an avid sailor. As a young man he regularly sailed along the shore of Cape Ann. One summer, Eliot and some friends sailed from Marblehead, Massachusetts to Mt. Desert Rock in a 19-foot knockabout in the fog and rough seas. It was a journey of well over 150 nautical miles and could have easily ended in disaster. The sea, of course, appears again and again in Eliot’s poetry.

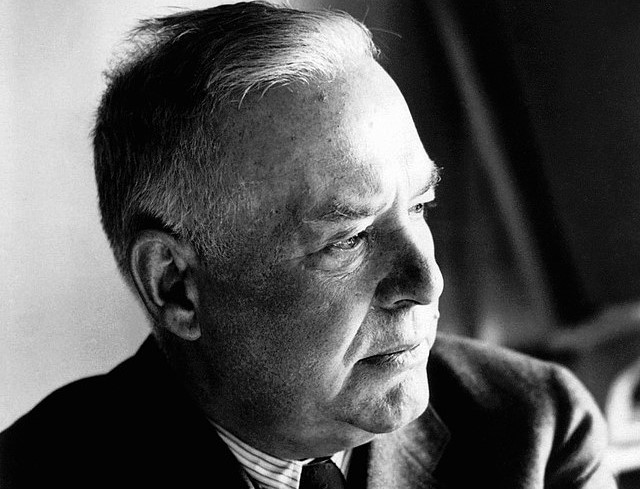

Both William Carlos Williams and Wallace Stevens collected art, but Stevens also enjoyed ordering exotic fruit in the mail. Stevens never traveled to Europe, even though he was a Francophile. But he did order nougat and fruit confit from Paris. On a day trip to New York in 1952, he tells José Rodríguez Feo that he plans to stop at the “fruit dealer” and do some other shopping:

Tomorrow I am going to New York to do a number of errands and otherwise nothing at all. Perhaps I shall have my hair cut. I know almost no one there any more, so that I am like a ghost in a cemetery reading epitaphs. I am going to visit a bookbinder, a dealer in autographs, Brook’s about pajamas, try to find a copy of Revue de Paris for December because of an article about Alain that it contains, visit a baker, a fruit dealer and, as it may be, a barber. An ordinary day like that does more for me than an extraordinary day: the bread of life is better than any souffle.

Stevens loved collecting bric-a-brac from around the world. “Happiness is an acquisition,” he wrote in his notebooks, quoting Epicurus with apparent approval.

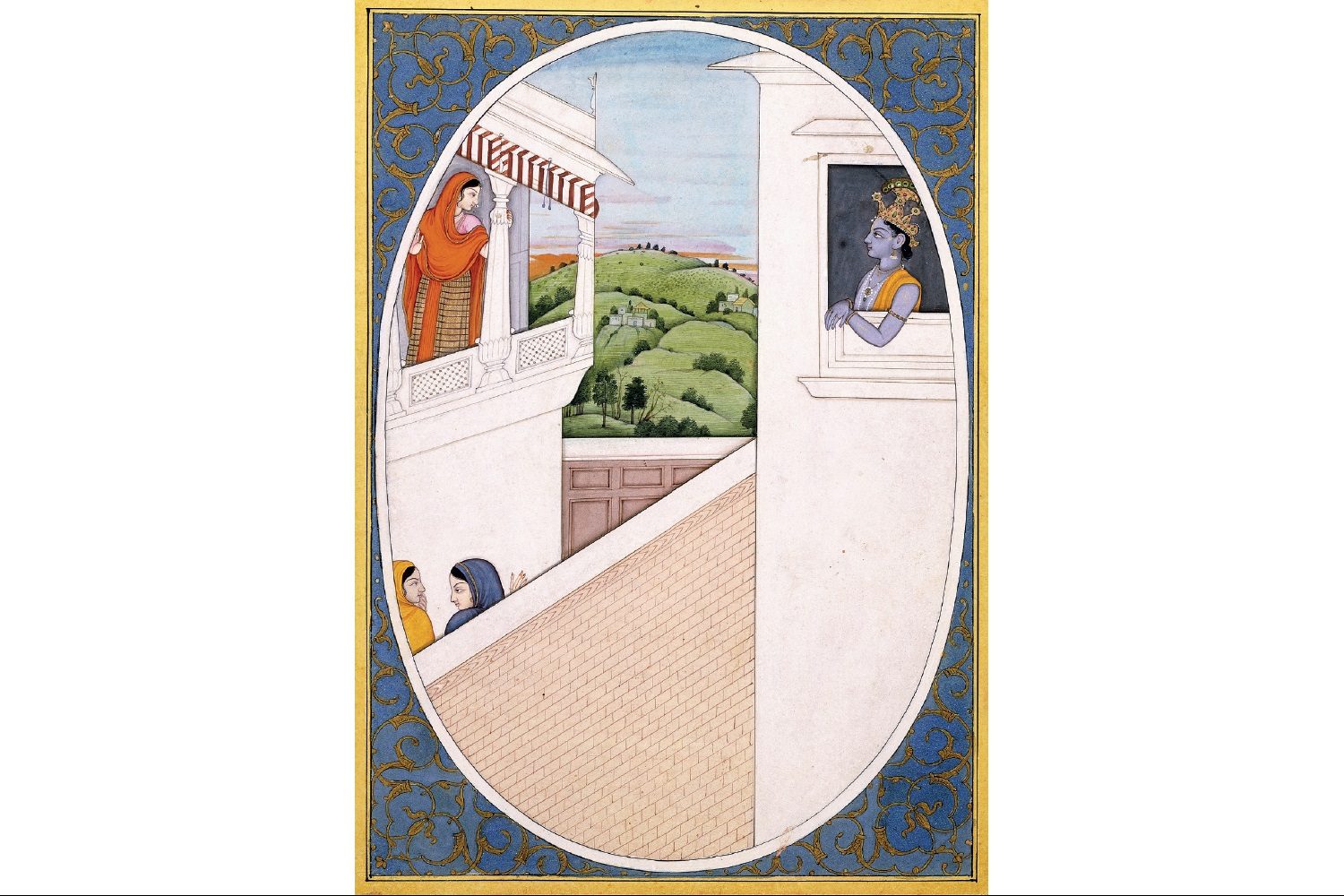

One of the things that fruit and the ordinary pleasures of life do for Stevens is to distract us from death, even if only momentarily. “Complacencies of the peignoir,” Stevens opens his famous “Sunday Morning,” “and late / Coffee and oranges in a sunny chair, / And the green freedom of a cockatoo / Upon a rug mingle to dissipate / The holy hush of ancient sacrifice.”

In the letter quoted above, Stevens goes on to write that:

It is almost as if everything was going to be all right again—as if the boards were to be taken down, the windows washed, fresh curtains put up, all on account of the arrival of a rich aunt who before she leaves will whisper in my ear that she intends to leave everything to me, including her chic little villa in Almendares.

There is something magical about stuff for Stevens. It announces, like fruit after spring, that death may not have the final word. His poem “The Emperor of Ice-Cream,” as Helen Vendler has noted, describes a wake. There is a dead woman (“cold…and dumb”) laid out, her body covered in “embroidered fantails.” But the speaker calls in “the roller of big cigars” who whips up ice cream for everyone as boys bring “flowers in last month’s newspapers.” “Let be be finale of seem,” the speaker states in the penultimate line of the first stanza. It’s an ambiguous phrase, stating both that death ends all possibilities and that living in the present (“be”) is the proper response to death.

But fruit, for Stevens, does more than this. He concludes his “Study of Two Pears” with the remark that “The pears are not seen / As the observer wills,” which is to say, in the context of the poem, that the pears do not conform to the observer’s view of them as mere fruit. “The pears are not viols, / Nudes or bottles. / They resemble nothing else.” They cannot be captured by metaphor. They are a testament of something irreducible.

He makes a similar point in his poem “In the Clear Season of Grapes,” where “a platter of pears, / Vermilion smeared over green” are “arranged for show” on a table in a house. He compares the pears to mountains against the sea and says that both the mountains and the pears mean “more than that” — that is, they are more than just a “show.” What “more” they mean Stevens doesn’t say, but he concludes the poem by asserting that they do, in fact, mean

Much more than that. Autumnal passages

Are overhung by the shadows of the rocks

And his nostrils blow out salt around each man.