Ronan Farrow is currently the most wonderful wunderkind in the United States, at least on the Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor. Former news chat show host for the MSNBC network, Rhodes Scholar and former foreign service officer, recent winner of a Pulitzer Prize for exposés on nasty sexual misconduct which brought down both Harvey Weinstein and the attorney general of New York, author of a new book of foreign policy deep thoughts and gossip. And all at age thirty and half! Not only does Farrow embody the anti-Trump zeitgeist right now, he has a freehold on the future, whether inside the next Democratic administration or in broadcast media.

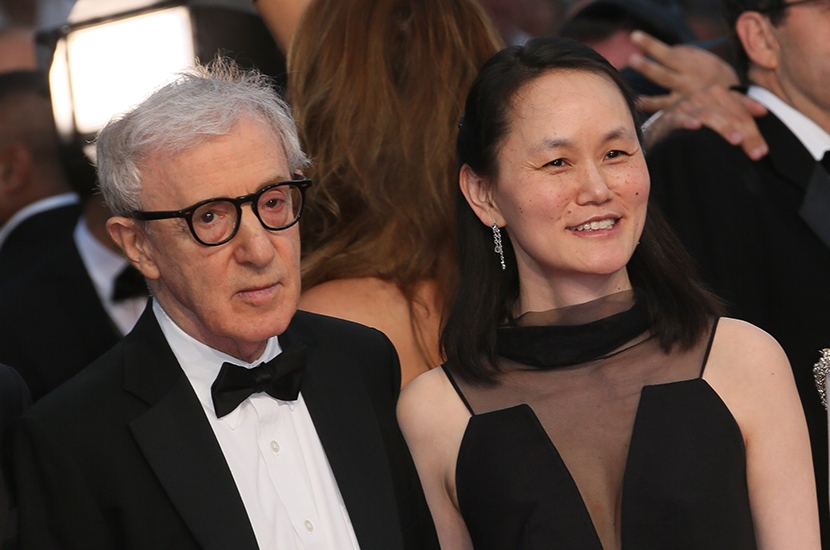

His ma is Mia Farrow; his paternity, complicated. Legally, dad is Woody Allen but his mother suggested five years ago that his biological papa might in fact be her ex-husband Frank Sinatra. In the protracted tabloid mess of Allen running off and marrying his adopted daughter, Ronan’s sister Soon-Yi Previn, and Mia Farrow’s accusations that Allen molested their stepdaughter, Dylan Farrow, Ronan is, unsurprisingly, estranged from his dad.

Before all that, Ronan was raised in Mia Farrow’s household with eleven siblings, eight of them adopted from overseas. A frequent travelling companion for his mother on her jet-set humanitarianism as a UNICEF Good Will Ambassador, Ronan developed a global sense of responsibility for the world’s problems.

After graduating from Bard College at the astonishing age of 15, he worked for UNICEF then took a degree at to Yale Law School, an institution which is something like the Vatican for the Democratic Party. (Bill and Hillary are grads.) After working as a foreign service officer–more about which in a minute– he started but did not finish a Rhodes Scholarship at Magdalen College, Oxford, then went on to host his own daytime news show at the Democratic-oriented MSNBC network.

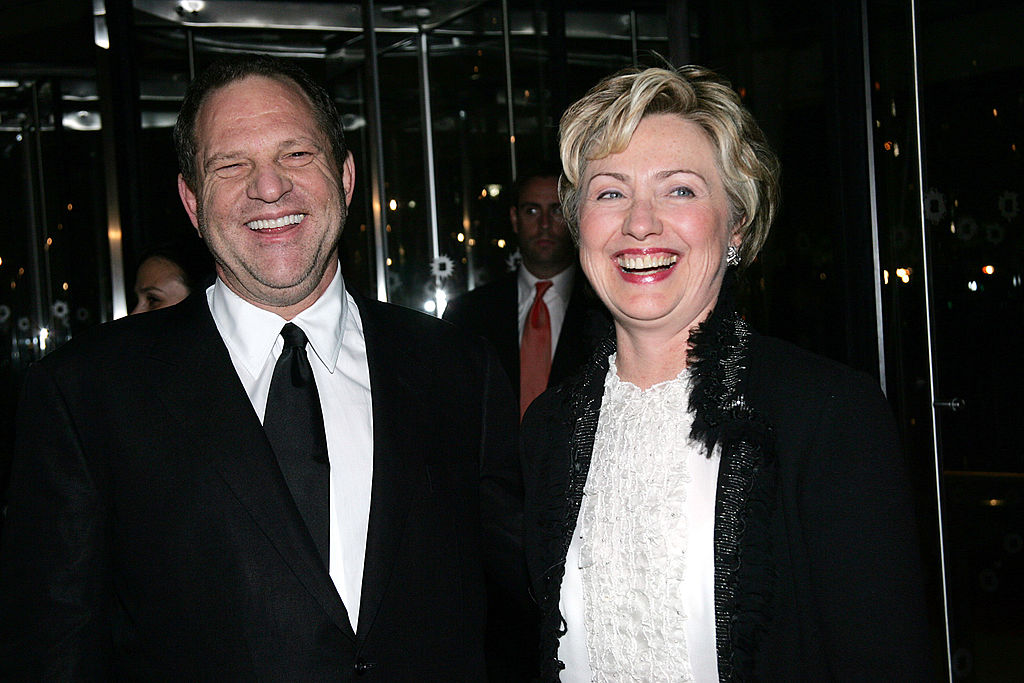

Although Farrow was seemingly incubated to serve the Democratic Party, he has been impressively nonpartisan with his investigative reporting. In fact both his big exposés have revealed sexual misconduct by men who were major Democrats.

The Weinstein allegations disgusted everyone but surprised few; the producer’s conduct was widely whispered about and well-known in Hollywood. The real challenge for Farrow (and for the New York Times team that he was racing against for the scoop) was to find enough women to go on record publicly and credibly and then to withstand the pressure coming from Weinstein’s massed phalanxes of attorneys.

Much more surprising were the allegations against liberal feminist Eric Schneiderman, who resigned his elected position as New York State Attorney General just hours after Farrow’s scoop of abusive behavior to women, co-authored by Jane Mayer, hit the New Yorker website. (And I would admire Farrow’s scoops even if one of Schneiderman’s two named accusers were not an old friend of mine.)

Unsurprisingly, the #MeToo moment has been more disruptive in the Democratic Party and its constituencies than among Republicans. For instance Al Franken, the comedian who became a Democratic Senator of his native Minnesota, resigned quickly after various alleged sex-pest misdemeanors came out last fall. Compare that to the pitched battle waged by Eric Greitens, the (at the time of this writing) Republican Governor of Missouri, accused of sexual violence and by his female hair stylist with whom he was having an affair and currently facing trial. Even though party brass have turned against Greitens, he maintains much support with the GOP base and refuses to step down. For many Democrats, “patriarchy” has come to be a slur but for the modal Republican voter, the word has a nice comforting ring to it, redolent of ball park, steakhouse and what might have been had things worked out better in family court.

When Farrow’s MSNBC show was cancelled last in 2015, and he left the network last summer, there was an algae bloom of schadenfreude as to this golden boy’s first public brush of non-success. But now it’s NBC that looks like a bunch of complicit dopes alarmingly ready to buckle under legal pressure from Weinstein’s attorneys. (Farrow for his part has moved on to HBO with deep budgets and wide creative latitude to make a series of documentary films, the highest calling of today’s upper-class liberals.)

For all Farrow’s valiant work, one tinseltown rag called him “the Hollywood Prince who torched the castle.” But Farrow is less enfant terrible than the kind of well-mannered young person that old people can fawn over and adore.

If Farrow wants it, he has a prominent place in the foreign policy apparatus of the next Democratic administration for the taking. What he will bring to the statecraft is a question answered by Farrow’s new book, War on Peace: The End of Diplomacy and the Decline of American Influence.

The book is both a gossipy memoir of Farrow’s time in the U.S. diplomatic corps (fun, and of real value) and a polemic against the militarisation of U.S. foreign policy. Since Clinton, the general trend in Washington has been to slash the diplomatic budget while allocating more and more tasks and funds to the military. Trump, bless him, has accelerated this: his first Secretary of State, oilman Rex Tillerson, called in the consulting firm Insigniam to administer a 27 percent budgetary amputation, slashing roughly $10 billion out of its $52.8 billion annual budget. Foggy Bottom is increasingly a seedy back office to the Pentagon, responsible for public relations for the troops and little else. And if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail: a militarised foreign policy-making process will typically yield military responses to any problem.

Not everyone is happy about this, including many in the military high command. As General James Mattis said in 2013: “If you don’t fund the State Department fully, then I need to buy more ammunition ultimately.” (Mattis has made considerably less noise about this since becoming Trump’s Secretary of Defense.)

Holbrooke

Farrow records his time with his great mentor, Richard Holbrooke, the hyperactive American diplomat and investment banker who at the time of his death was Obama’s top non-military envoy for Afghanistan and and Pakistan. Farrow portrays Holbrooke as a visionary American statesman who prized diplomatic over military solutions, a skeptic of counterinsurgency warfare since his own days as a stripling State Department officer in Vietnam, and then forger of the Dayton Accords which quelled the Balkan slaughter. Others could accurately remember Holbrooke as a proponent of the Bush-Cheney invasion of Iraq and supporter of Obama’s initial troop escalation in Afghanistan.

Even if Farrow is too close to his material to see it clearly, he does bring an acute understanding of the politics, bureaucratic rivalries and weaponised uses of leaks and media in foreign policy. He also provides a chilling example of how alarmist security mania at home can stifle diplomacy wit his admiring portrait of Robin Raphel, a career U.S. diplomat and expert on central Asia who upon retiring was the object of doltish persecution by the FBI who found her communications with Pakistani nationals to be inherently suspect. But such yokel resentments have always dogged diplomats, the suspicion being that just by living among foreigners they have become treasonously alien themselves.

Demilitarising in practice

Farrow’s big idea is that U.S. statecraft needs to be demilitarised. It’s hard to disagree with this slogan but what does it mean in say, Yemen, where a Saudi-led coalition, with U.S. weaponry, targeting and mid-air refueling, has bombed that nation into a humanitarian crisis with grave risk of epidemic and famine. Surely this is a theatre where fresh thinking from an American foreign policy up-and-comer is badly needed?

But looking to the index of Farrow’s book one finds that Yemen gets exactly one brief mention, the same number as “Hamlisch, Marvin” and “Jolie, Angelina.” And this despite the growing push among the Senate’s most conservative Republicans and progressive Democrats to cut off military aid to the Saudis!

OK, how about Libya? Surely Farrow has something interesting to say about how a diplomatic approach might have better addressed the insurgency against Gaddafi there, now that the Franco-British-American regime change operation has left the country in violent chaos? (This case ought to be doubly interesting for Farrow as the U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, a Republican, opposed that war whereas humanitarian diplomats like Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Samantha Power backed it to the hilt.) But Libya too is mentioned only in passing, exactly once, as often “Portman, Natalie” and “Sorkin, Aaron.”

One looks in vain for any fresh thinking on how to demilitarise U.S. policy on Syria, let alone bold ideas for de-conflicting that internationalised civil war itself. What about full diplomatic recognition of Iran to induce them to retrench? A grand bargain with Russia including full rights to their dinky blue-water port at Tartus? Direct talks with Hezbollah? This diplomatic program of course does not carry any guarantee of success–but then neither does violent regime change. More importantly, all of these ideas bump up against domestic political constraints in the U.S.–like ending massive aid to Egypt, which Farrow judges as “not politically realistic.”

A strategic void

Diplomats used to talk about strategy: which alliances are worth keeping, which client-states are worth dropping, the costs of peace and war. You won’t find any of that in War on Peace where there is remarkably little questioning of the fundamental substance of American statecraft, a void that is echoed in the U.S. foreign policy discourse in general. For Farrow, diplomacy is mainly a matter of procedure, or governmental style, not of substantive goals and outcomes.. As for the content of U.S. diplomacy, they young man has faithfully internalised its precepts: of what is “not politically realistic.”

Farrow is good at pointing out the enormous differences between the statecraft of Obama and Trump. Alas, Farrow is even better at airbrushing over the continuities between the two presidencies, and these too are significant. Farrow chides Trump for giving local military commanders more discretion in Somalia, but it was the Obama administration that expanded the legal and military scope of that mostly ignored war in the last months of his presidency. And Trump’s escalation of a couple thousand troops in Afghanistan is not much compared to Obama’s “surge” of 30,000 soldiers in 2010, all with the backing of his diplo-humanitarian angel choir.

A new Samantha Power?

Farrow today strongly resembles the Samantha Power of 15 years ago, when the former American ambassador to the U.N. was a fresh-faced young journalist, lawyer-activist and Pulitzer-winner herself. Their books follow a similar recipe: take an unobjectionable humanitarian nostrum and apply it selectively, artfully, advantageously. According to Farrow, Power’s Pulitzer-winning A Problem from Hell: American in the Age of Genocide is “a book on America’s failure to confront genocide around the world.” In fact Power’s book was a master class in strategic evasiveness, hilariously tight-lipped (or silent) about the postwar genocides to which Washington has lent a complicit hand. Farrow’s evasions and silences aren’t quite a severe, but they do show that the young man knows when to be quiet, lest he give offense. This is not the kind of bold fresh thinking that U.S. foreign policy needs.

Now, it may seem frivolous and ungrateful even to complain about a young up-and-comer making a less-than-perfect argument for peaceful diplomacy while the current U.S. president rampages like a marigold Godzilla, tearing down multilateral agreements and stomping all over the U.S. State Department and now lurching to war with Iran: a Dick Cheney foreign policy without the Methodist hymns to freedom and democracy. Hey, don’t we need a ray of light in the Trumpzeit?

But in dreams begin responsibilities, and today’s beamish boy is likely tomorrow’s Deputy Assistant Secretary of State or perhaps even U.N. envoy. It’s good to see these people coming form a long way off, and as clearly as possible. Recall how Samantha Power parlayed her pop-moralising into effective advocacy for troop escalation in Afghanistan and regime change in Libya, and Yale Law dean Harold Koh used his human rights credentials to formulate the State Department’s legal rationale for Obama’s drone assassinations, who knows what military-industrial applications young Farrow might be repurposed for in the fullness of time?

Farrow’s blazing and varied career so far is symptomatic of today’s Democratic Party. They are a slowly chugging but mostly reliable machine for social liberalisation, and Farrow truly earned his Pulitzer in helping to bring about the #MeToo moment. But when it comes to structural issues like ravening inequality of wealth and opportunity, or the post-9/11 forever war, Democratic party grandees and their brilliant young protégés show a dearth of both vision and guile. All of which is to say, we can expect Farrow to go far in the next Democratic administration.