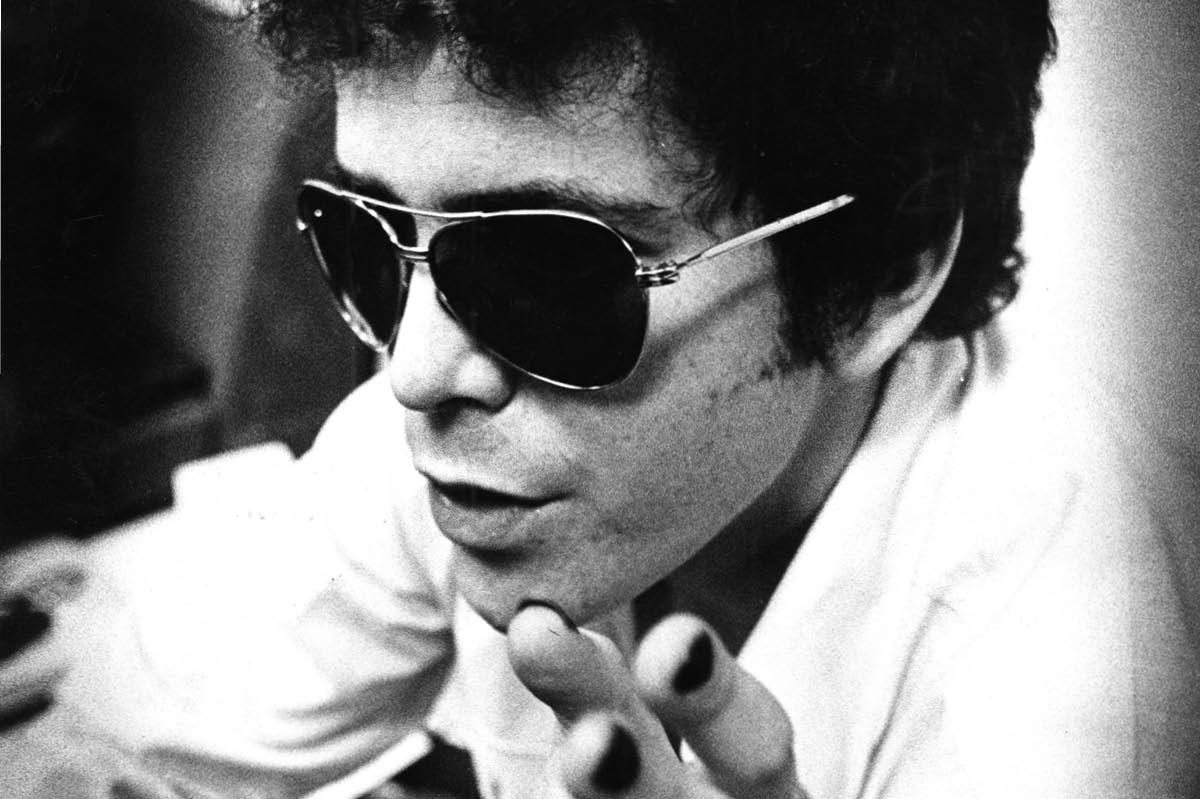

There’s a case to be made for John Cale being the most daring ex-member of the Velvet Underground. Lou Reed redefined the transgressive possibilities of literate three-chord rock ’n’ roll. Cale, arguably, has travelled even further.

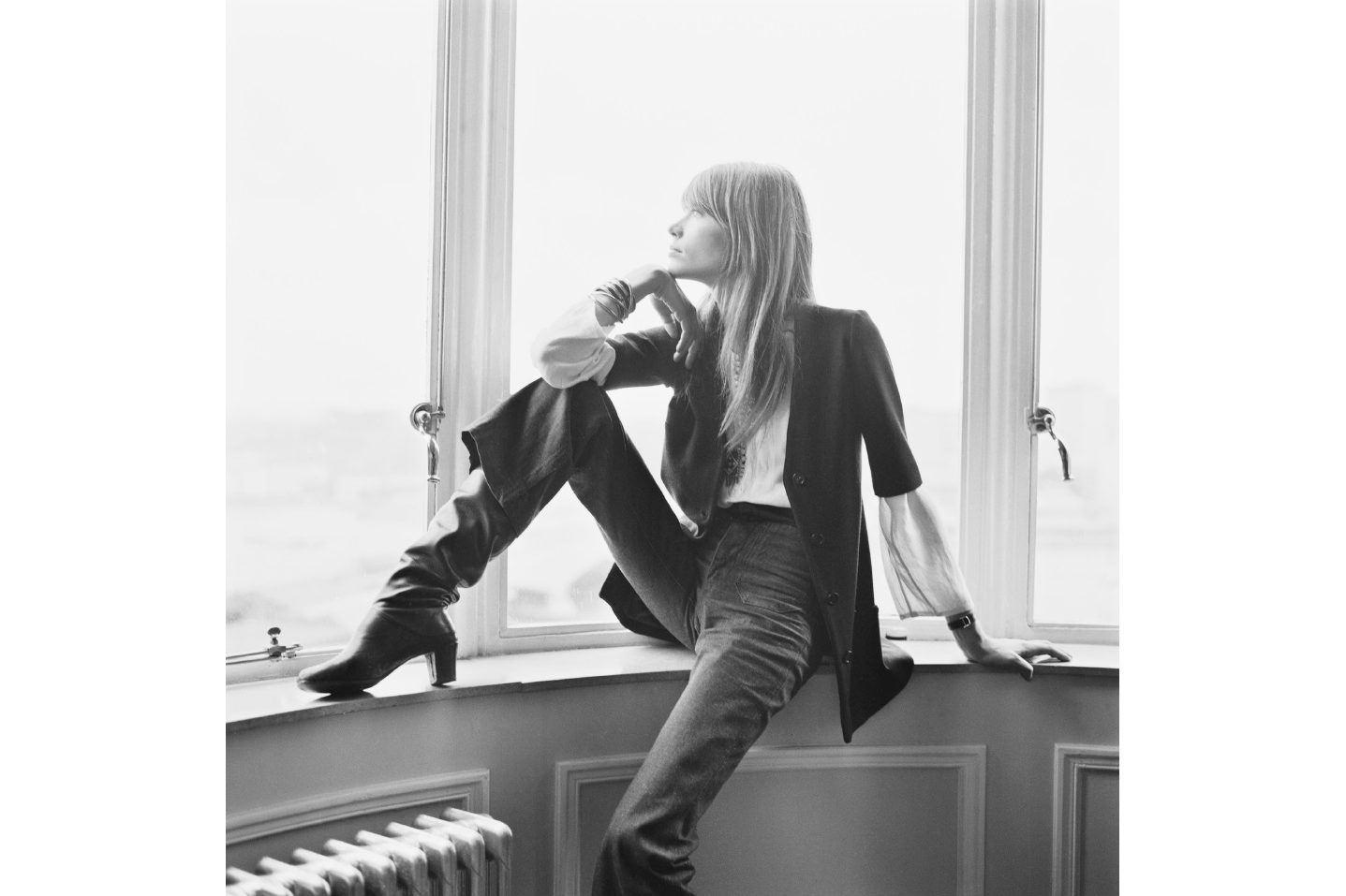

A Welsh miner’s son who won a scholarship to Goldsmiths, Cale engaged with the early flowerings of Fluxus before mixing with John Cage and La Monte Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music in New York’s downtown avant-garde scene. His droning viola, hammering piano and relentless bass brought the serrated edge to the Velvet Underground’s art music. More than anyone in the band, he rendered Reed’s whiplash words in sound.

After leaving in 1968, Cale’s solo career has often been exemplary: Paris 1919, Fear and Music for a New Society are particularly outstanding records, made during periods of intermittent derangement. Cale drank and drugged his way through the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties with at least as much abandon as Reed. He once chopped off the head of a chicken on stage and his version of Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel,” performed wearing a hockey mask, like some driller-killer from a video nasty, is appreciably berserk.

Reed had few peers when it came to — sometimes performative — obstreperousness; he could be a thoroughly unpleasant interviewee, as I can attest. Cale, though more mercurial, is no slouch either. His voice, which fluctuates between a purr and a growl, is indicative. He’s like one of those cute animals which draw you close only to bite your hand off.

Anyway, it’s not a competition, but you get the point. This is an artist of proven substance. And while Reed is nearly ten years’ dead, Cale is still pushing forward. Now eighty, Mercy is his first record of new material in more than a decade. It’s thrillingly claustrophobic, like being locked in some grand Gothic cathedral with a mad organist as the sound rolls up and around the walls, or subjected to a prolonged immersion with your own ghost in an isolation tank.

This is January music, all right. Death crawls through the twelve lengthy ruminations, some of which are exercises in sonic curiosity rather than songs. “Marilyn Monroe’s Legs” is barely there at all, mostly consisting of just a pulse and eerie echoes from the cloister.

Like Leonard Cohen, Scott Walker and David Bowie, Cale has discovered a dark new energy in older age. Mercy variously recalls the wry resignation of Cohen, the jarring terror-music of later Walker, and the somber grandeur of Bowie’s Blackstar. The influence of the latter is particularly evident on the title track, with its disassociated choral voices, skimpy electronic backing and assorted whirring noises, and on “Everlasting Days,” where faux-orchestral elegance elides into ferocious rhythm.

Crucially, Cale is clearly still also listening to modern music; his work buzzes with hip hop, trap and R&B inflections. He plays most of Mercy himself, bringing in younger collaborators to add brush strokes to the canvas. They include Animal Collective, Sylvan Esso, Laurel Halo, Tei Shi, Actress and Weyes Blood, who features as a kind of Nico proxy on the cool, clicking “Story Of Blood.”

Occasionally these slow, longform pieces, not always heavy on melody, wander a little, but generally Cale holds our interest. Mercy achieves the oddly admirable feat of sounding both becalmed and terrified all at once. “Noise Of You” is languid lounge-funk for vampires; the Blue Nile in hell.

Lyrically, the record seems to gather accumulated universal disasters of the past ten years, plus a few older ones from Cale’s own past, and screw them into a big ball of anxiety. On “Everlasting Days,” his gritted-teeth murmur measures the obscenity of modern life against the obscenities of history. “Time Stands Still” depicts Europe sinking in the mud, the “savagery of the Church of God” making sure it stays there. Underneath it all is the unmistakable sense of reckoning, but also valediction. “It’s later than you think,” he warns. “I’m going back to get them, my friends in the morning/ Bring them with me into the light.” There is even a song for another late band mate, Nico, a “moonstruck junkie lady.” It would be no great surprise if Mercy proved to be Cale’s final record.

This is not an easy album, but its sometimes beautiful bleakness comes with slivers of hope and moments that portray love as an escape room. Mercy is music for the 3 a.m. night sweats. In that sense, perhaps, it is typically Cale, yet it also feels like the work of an artist still breaking new ground. For a man now in his ninth decade, that’s one reason to be cheerful, at least.

Mercy is out now on Double Six/Domino. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.