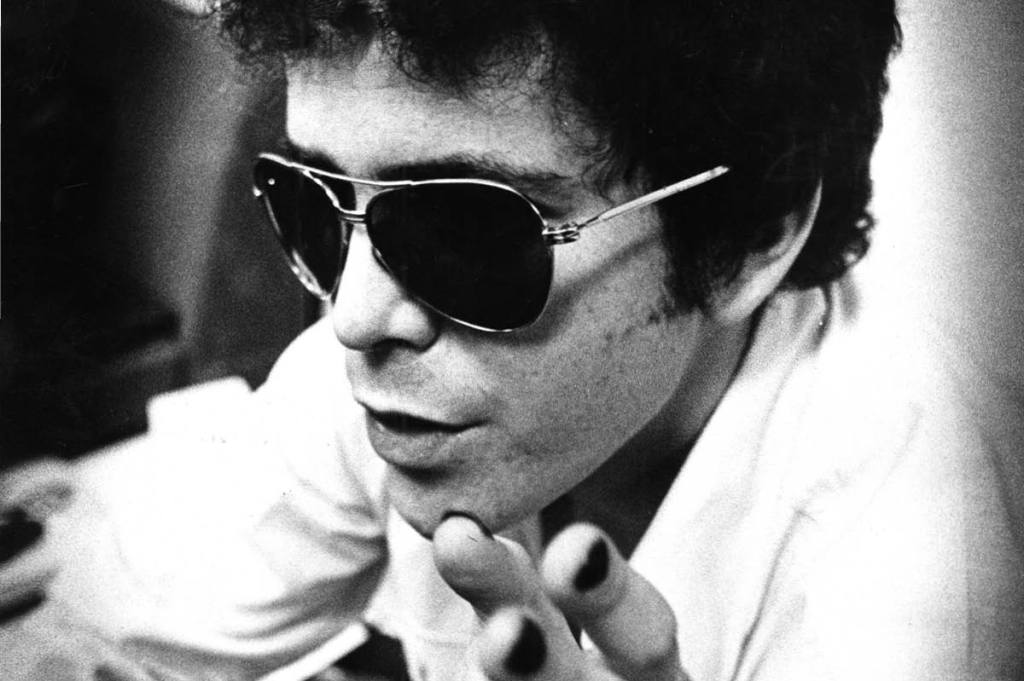

Before “Walk On The Wild Side” changed everything for Lou Reed in 1972, bringing him status and bolstering his bank account, he had been lead singer of the Velvet Underground, a group, as managed by Andy Warhol, that served up songs about drugs, gender-bending and sexual fetish, all designed to crash the boundaries of what polite America considered acceptable. The great thing about Velvet Underground songs was that musically, too, they transgressed: drone-based harmonies progressed glacially as rhythmic impetus stuttered. The big problem with the Velvets, in terms of finding any wider audience beyond self-confessed weirdos who hung out with Warhol, was that virtually nobody wanted to hear drone-based harmonies moving glacially or rhythms that fragmented. Where was the fun in that? But then “Walk On The Wild Side” — itself a song about blowjobs, transsexuality and male hookers — demonstrated that Lou’s peculiar vision of weird could work in the mainstream too.

Hearing Reed, on his 1978 album Live: Take No Prisoners, devote a whole seventeen minutes to not performing “Wild Side,” the one song anyone who ever attended a Reed gig wanted to hear, has always to me felt like the essence of Lou Reed. It’s also a prime example of what Will Hermes, the author of this pacy, gloriously written new biography, terms his subject’s determination to “live as he pleased” while “answering to no one.” Even the sniff of a favorite riff is usually enough to induce a state of orgasmic ecstasy in an audience, but Reed utterly refused to play that game. On Take No Prisoners, for five times longer than the duration of the original record, Reed teased his audience with hints that he might be about to feed them his most famous song. As its underlying riff churned in the background, he embarked instead on a shaggy dog story, a highly dubious account of how he came to write the song, peppered with catty asides aimed at his archnemesis, the rock critic Robert Christgau, and with insults hurled at the audience. The off-the-cuff dexterity of his wit was pure Lenny Bruce, while the rhythmic stampede of his delivery invoked the high-velocity improvisational attack of his great hero, the free-jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman.

Antagonism toward interviewers was his default setting, and Reed’s eyes would roll uncontrollably at what he considered their predictably dumb questions. But like many music journalists I have fantasized that, with me, things would surely have been different. My favorite moment, I’d explain, was when he didn’t sing “Walk On The Wild Side” at the Bottom Line in 1978. Immediately he would realize that I was a fellow crank — but, truth is, he’d have concluded that I was an asshole too.

Hermes dedicates copious space to teasing out the distinction between Reed’s obstinate defiance, which was integral to his art, and his tendency to lash out when that rock star ego got the better of him, when he assumed that everyone who wasn’t Lou Reed was an asshole (his insult of choice). Had Reed’s family — originally the Rabinowitzes — not moved from Brooklyn, where he was born in 1942, to Long Island, matters might have been different. But the humdrum rhythms and docility of Long Island, where his father was employed by a company that manufactured potato chip packets, sent Reed into tailspins of depression and nervous anxiety.

He was sent for electroconvulsive treatment, a devastating experience that ended up doing more harm than good. His childhood was scarred by panic attacks, the social embarrassment that came with being dyslexic and eruptions of uncontainable fury. Although the evidence remains inconclusive, his electric shock sessions might have been intended as a “cure” for another of his apparent “difficulties” — sex with girls, nice enough, was merely a pastime compared to his all-consuming, burgeoning passion for boys. Middle-class Long Island was not a great place to grow up queer.

But by page seventeen, Hermes has the sixteen-year-old Reed in a Manhattan studio, recording with a trio of schoolfriends with whom he had cooked up some Little Richard and doo-wop songs, tasty enough to impress an A&R man for Mercury Records. For all his emotional growing pains, Reed had little difficulty attaining sufficient proficiency on guitar to hold his own in a recording studio alongside a backing group that included the great rhythm and blues saxophonist King Curtis. Hermes informs us that Reed rebelled against sports classes and military-style boot camps during his teens; it comes as no surprise, although it seems more significant, given his eventual whip-sharp technical chops, that he stubbornly refused to take formal guitar lessons. He had no desire to play like anyone else. Playing guitar was his way of distilling the music he was discovering into something to call his own.

Reed had a natural predisposition toward music that questioned what music could be. Appreciating Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Big Bill Broonzy came as standard, but he was never content to leave it at that. From the perspective of 2024, it’s easy to forget just how marginalized and out-on-a-cultural-limb musicians like Coleman and pioneering free jazz pianist Cecil Taylor were, yet Reed centered himself inside their music. He heard the Coleman Quartet play the Five Spot Café in the Bowery in 1959, itself a landmark moment in the evolution of modern jazz, and named a college radio program he hosted after Taylor’s piece “Excursions On A Wobbly Rail.” He also found himself entranced by Moondog, the legendary blind street musician, who, from the corner of Sixth Avenue and Fifty-Third Street in Manhattan, would improvise against the wail of sirens and the resonant honks of tugboats, a music that, Hermes writes, was “unconventional, sophisticated, kooky yet inviting.”

Music that questions music also questions society, and soon enough Reed was aiming his work at the drab, decidedly uncurious atmosphere of conformity that had blighted his childhood. He wondered for a while whether he ought to be expressing his disquiet about the world as a writer. In defiance of his dyslexia, he had turned into an insatiable reader: James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Edgar Allan Poe, William Burroughs and Hubert Selby Jr. clawed open his imagination. He also absorbed Sylvia Plath’s gruesome accounts of enduring electric shock treatment, and acquired an appetite for Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels as a guilty pleasure. But music claimed him back and Hermes’s thought that Reed’s goal was “merging the basic, ecstatic joys of rock ’n’ roll with lyrics that aspired to do what literature does” feels very much the point.

The author has poured so much detail and original research into this biography (the first to have been published since the Reed archive opened at New York Public Library) that identifying a gap at the center of the book seems almost churlish — but for all Hermes excels at documenting the “whys” and “whens” of the life, the all-important “hows” of how Reed’s music functioned as a consequence of them are missing in action. Rock biography is not renowned for musical analysis, and writers who can’t, shouldn’t. Then again, nobody would conceive of writing a biography of Picasso without defining Cubism.

Listening to Reed’s recorded legacy — from the Velvet Underground, through the exceptional sequence of solo albums released between 1972 and 1987 on RCA/Arista, which include Transformer (with “Walk On The Wild Side” and his other signature song “Perfect Day”), Rock ’n’ Roll Animal and The Bells, and on to later projects like Magic and Loss and The Raven — you realize that a finely-honed counterpoint between lyric and music is the secure berth that allowed Reed’s harmonies to slip their moorings. Velvet Underground songs like “Heroin,” “All Tomorrow’s Parties” and “White Light/ White Heat” still sound so stark and granite today because the rhythmic energy of the words obliges the music to behave against rock ’n’ roll type: the words demand to be heard, must never be overwhelmed by equally hectic music.

Songs like “Heroin,” “Wild Side” and “Teach The Gifted Children” all derived their unique flavor from Reed’s abandoning the anchor around which virtually all rock and pop had hitherto been rooted: the fifth and first of the scale. His ear led him to stress the fourth and first instead, which knocked the musical grammar off-kilter and allowed for greater ambiguity, a useful tool in songs about fluid sexuality. Once such musical fundamentals get nailed down biographical details click into place more firmly. Reed’s main collaborator in the Velvets, John Cale, was that rarest of rock musicians: a Welsh viola player, with a background in classical music, obsessed with the experimentation of his near namesake John Cage and with the inching-along works of La Monte Young, music later termed minimalism. Cale’s penchant for sustained drones on his viola often led him to oscillate between fifths and fourths. The two men had a troubled relationship, but their ears were in alignment.

Which no doubt is precisely the sort of “asshole” analysis that would have riled Reed had I ever interviewed him. Hermes did interview Reed and seems unusually well attuned to his subject, while resisting any temptation to soft-pedal. That Reed could be violent toward his partners never makes for comfortable reading, and accounts of his petty takedowns of waitstaff in restaurants and his delight in inflicting humiliation, although part of the mythology, are wretched. Such cantankerous behavior increased as health problems stacked up during his final years, but he had also found blissful happiness with his third wife Laurie Anderson. The final chapters are filled with accounts of the pair disappearing into the New York night together: always a show, a gig, a screening, an exhibition to attend. His time was running out, and illness became another antagonist, something else to defy.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply