Having a saint in the family is dreadful, They’re often absent, either literally or emotionally, and because they’re always thinking of higher things they can’t be expected to do prosaic stuff like take the rubbish out or pay the gas bill. They tend not to enjoy jokes, much less teasing. Worse still, they’re convinced they’re right about everything. Street angel, house devil, as the old saying has it.

Do-gooders crop up here and there in fiction, from Dickens’s bustling, bossy Mrs Jellyby in Bleak House through to the long-suffering Lady Marchmain in Brideshead Revisited to Ian Bedloe, the miserably stubborn hero of Anne Tyler’s brilliant Saint Maybe. Carol Shields’s latest book, Unless, is about a daughter who drops out of university in order to sit, mute, on a street corner with a sign saying ‘Goodness’ around her neck. Imagine how annoying.

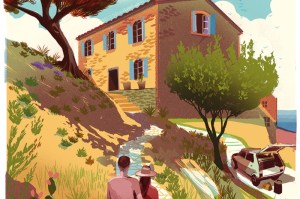

The Dutch House does not at first seem as if it’s about the chaos a saint brings to the family she abandons. It appears to be a marvelously romantic and evocative novel about the nostalgic pull of a lost home. This is the Dutch House, an opulent, sprawling, chandeliered mansion, the childhood home of the narrator Danny Conroy and his beloved sister, Maeve. When their mother disappears, their lives are blighted by the arrival of a wicked stepmother with two little girls of her own. Before long, she has ousted Maeve from her bedroom and banished her to the attic. When their father dies suddenly, they are exiled from the house forever.

For decades afterwards, and for much of the novel, the siblings go and park opposite and sit in the car, smoking and reminiscing. The longed-for house in Le Grand Meaulnes comes to mind: there is a similarly pervasive sense of having lost a paradise which cannot be regained.

The Dutch House is beautifully written and often tender, but the central characters aren’t vivid enough for this book to be among Patchett’s very finest. The siblings feel a bit flat and underdeveloped. Danny’s lifelong wish is to work in property development, like his father. At Maeve’s urging, though, he goes through all the years and slog of medical school in order to wring as much cash as possible out of an educational trust which is their only legacy. The fact that he never has any intention of practicing as a doctor makes this less than credible. Surely he could have cost the trust plenty of money by doing one or more law degrees?

Maeve is described as a wonderful woman, loving, loyal, kind. Yet she is willing for her brother to undergo almost a decade of study in a subject which is of no interest to him, purely to piss off their stepmother. She also takes a bizarre dislike to Danny’s wife, making her darling brother’s life much harder than she has to.

But just as the siblings were starting to annoy me, Patchett introduces their long-lost mother into the story. It became apparent that the first two thirds of The Dutch House are in fact describing what the loss of this allegedly saintly person has done to them: how stuck it has made them, how they have had to cling together. It seems as if their rather two-dimensional characters are the result of childhood trauma.

This becomes that rare thing: a novel which reveals greater riches on second reading, once one knows how it works out. The final section is wonderful. Patchett avoids any easy answers, and reconciliation turns out to be as bitter as it is sweet. ‘When you think about saints, I don’t imagine any of them made their families happy,’ someone says to Danny. Too true.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.