Barbara Comyns’s reputation rises and falls like a Mexican wave, making her one of the most rediscovered novelists of recent times. She’s credited with anticipating Angela Carter and for being in the vanguard of tackling themes of traumatic dissociation and the realities of childbirth. Yet younger, trendier writers have regularly eclipsed her.

Aged twenty-nine, Barbara was broke: a single mother who’d weathered affairs, an abortion and a suicide attempt

Every fan remembers their first Comyns novel: the visceral jolt of black humor, the sucker punch of stark horror. Knowing that she drew from life, we have longed for a biography, and hooray, it’s finally here. Avril Horner, emeritus professor of English at Kingston University, has given us one with Barbara Comyns: A Savage Innocence. It is packed with incidents both monumental and mundane. It skillfully interweaves life and literature and draws on family memories and unpublished private papers.

Horner promises not to “raid the work for evidence of the writer’s life;” but the truth is, a lot that is described in the novels did happen — not only macabre details, but sad episodes familiar from Comyns’s depictions of thwarted relationships and downtrodden women. Economic exigency — a significant factor in the novels — was also a driving force in Comyns’s life. After a privileged, if emotionally fraught, childhood, she was thrust into the world at eighteenth after the death of her father. Untrained for anything much, she struggled to keep afloat. Her first jobs included kennel attendant, poodle breeder, antiques dealer, piano trader, domestic help and artist’s model. Only in the last decade of her life — she died in 1992, aged eighty-five — did she enjoy economic security.

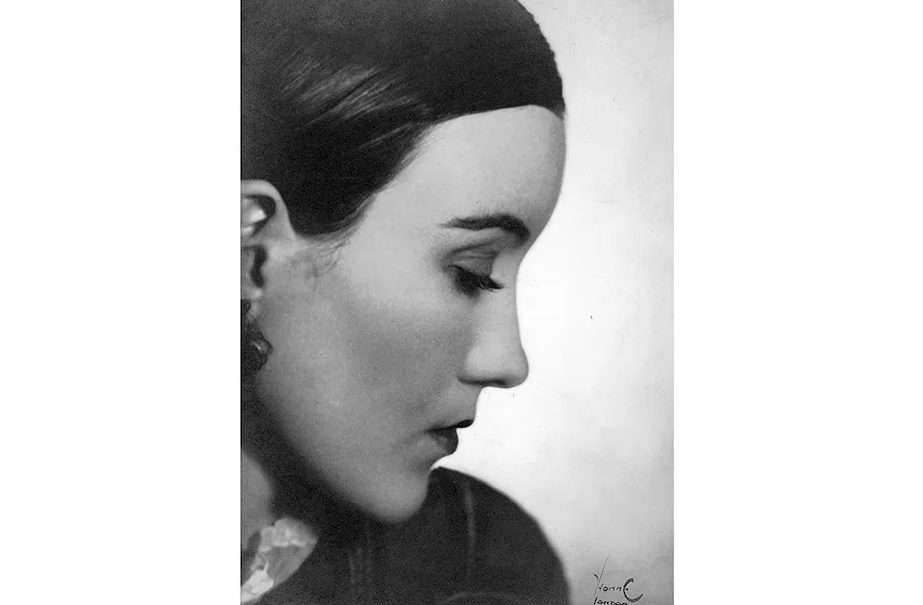

Comyns originally dreamed of becoming a sculptor, but art school fees proved impossible. Nevertheless, she embraced bohemian living, moved in artistic circles, and was influenced by Surrealism. Beautiful and magnetic, she inspired loyalty, despite moments when she frayed her friends’ nerves.

She married twice, and raised two surviving children, one by her first husband, John Pemberton, the other (who she pretended was John’s) by Rupert Lee, the former husband of John’s aunt. But it was Lee’s next wife, the wealthy Diana Brinton, who became Barbara’s lifelong on-off frenemy. Their complicated relationship makes for absorbing reading and seesawing sympathies.

Bohemianism was an unequal proposition. Like many women, Comyns sidelined her art to further Pemberton’s. Still, he felt constrained by responsibilities he’d barely assumed. Times were tough, and by the age of twenty-nine, Barbara was broke — and broken: a single mother who’d weathered affairs, an abortion and a suicide attempt. Circumstances improved when she got involved with Arthur Price, who, though “a bit of a crook,” mostly comes out well here. The two sometimes verged on criminality, but their schemes and adventures are fun to follow. He’d be immortalized in her 1987 novel Mr. Fox.

Comyns’s first book, published when she was forty, emerged from stories she told her children about growing up in Bidford-on-Avon, transformed into a startling work for adults. Sisters by a River introduced readers to the naive worldview that was to become a hallmark of her later novels, even when her narrators are adults.

Her second husband, Richard Comyns Carr, initially worked in the Foreign Office and MI6. They honeymooned in a cottage owned by his good friend Kim Philby, and hosted parties for a cosmopolitan circle including everyone from David Footman, the chief of the political section of MI6, to Graham Greene, Augustus John and Dylan Thomas. Greene crucially wrote to the managing director of the publisher Bodley Head advising him to keep an eye on Comyns — “a crazy but interesting novelist whom I started when I was at Eyre & Spottiswode.” We owe Greene a double debt for getting her into print, and for urging Carmen Callil to republish her in the now familiar Virago editions.

When Philby disappeared, Comyns Carr lost his job — the feeling being if he knew about Philby he was a traitor, and if he didn’t he was a fool. The couple decamped to Spain in 1956, staying there eighteenth years, always scrabbling to keep ahead of their creditors. Barbara worked there on her most celebrated novel The Vet’s Daughter, “a surreal, dark tale about human cruelty,” unlike anything else published in English in the 1950s. Kenneth Allsop called it “so original in its vision and beautifully exact in its writing that I am lost in admiration.”

But good reviews did not guarantee continued success. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, disappointment was frequent. Thankfully, Comyns set pessimism aside when she and Richard returned to England. She resumed writing, but the 1980s were often overshadowed by family dramas — not the least being Richard’s death.

The 1981 Virago edition of The Vet’s Daughter changed everything. Comyns felt emboldened to work on The Juniper Tree, with its fairytale references and surreal take on the domestic, and then Mr. Fox. In 1989 she brought out House of Dolls, not mentioning that she’d written it twenty years earlier, when it had failed to interest a publisher.

Her reputation waned again after her death, but this century has seen renewed admiration. While Horner’s biography occasionally suffers from repetition, it’s clearly a labor of love and should be received in that spirit. Let’s hope it encourages new readers to discover Comyns’s haunting novels and the compelling artist behind them.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply