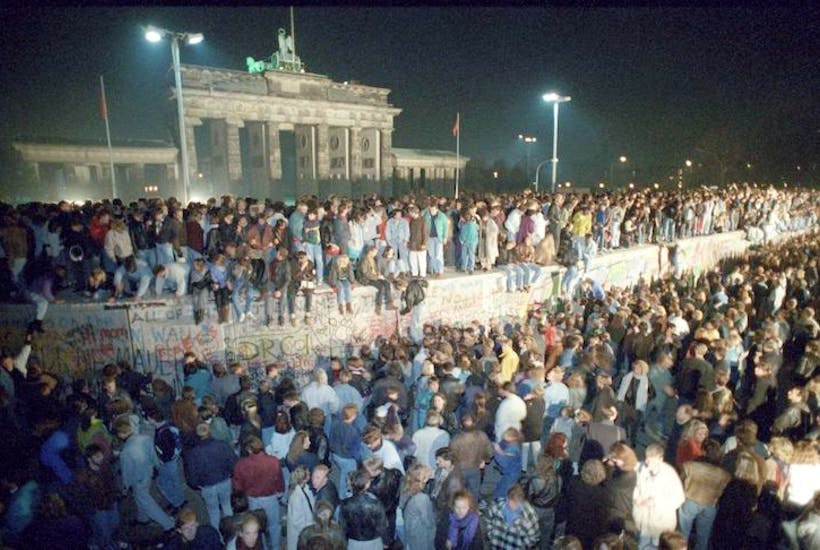

It is now 28 years and three months since the Wall came down. For Europeans and Americans, this is a pivotal moment in world history. Berlin has now been reunited for longer than it was divided. So where does the German capital and the German nation stand, a generation since that ecstatic November evening? Has this been that rare thing, a German story with a happy ending? Or have the fears of Margaret Thatcher and Francois Mitterand been confirmed?

When the Berlin Wall came tumbling down, West and East Germans were joyful – but the world looked on with baited breath. Thatcher was especially aghast. She dreaded German Reunification, and did her best to halt it. The British Prime Minster wasn’t the only leader to voice her concern. France’s President Mitterand was also deeply apprehensive. He realised reunification would inevitably result from what Germans call the ’Mauerfall’, but he wasn’t happy about it. He feared a reunited Germany might achieve even more than Hitler had in dominating Europe. So was he right?

If it hadn’t been for America, German Reunification might well have never happened. A master of foreign policy, George Bush Senior saw the bigger picture. His administration recognised that British and French concerns belonged to a bygone age. The Germans were now the good guys, and Gorbachev’s policy of Glasnost and Perestroika provided a unique window of opportunity, which wouldn’t remain open for long. Germany was also blessed with a shrewd and decisive Chancellor, Helmut Kohl. While Thatcher and Mitterand grumbled, Bush and Kohl acted – fast. They forged a new European order, with a reunited democratic Germany at its centre. All of Russia’s other Communist statelets soon went the same way.

German Reunification has been a remarkable success – not just for Germany, but for Europe as a whole. The Bundesrepublik is a model democracy, a bastion of human rights and a champion of international law. East Germany, a Soviet vassal state in the heart of Europe, has been brought safely into the Western fold. The Mauerfall inspired the peaceful liberation of Eastern Europe. All of Russia’s Warsaw Pact allies are now loyal members of Nato – even the three Baltic States, which were previously part of the USSR. Thatcher was right to predict that German Reunification would destroy the old world order, but it destroyed that old order in an entirely beneficial way.

No German armies have marched into neighbouring countries to reclaim territory lost at the end of World War Two. A Fourth Reich remains a fantasy, on the military front at least. It’s on the economic front that residual fears remain. The richest and most populous member of the European Union, Germany is Europe’s dominant economic power, and the dominant political power too. In spite of its domestic difficulties (specifically German worries about Islamic immigration from the war torn nations of the Middle East) its economy is booming. As Germany grows stronger and stronger economically, it will inevitably wield more and more political power.

The Europhile position, both in Germany and throughout Europe, is that the European Union constrains German power, by locking the Fatherland into a partnership with the other 27 (or, after Britain leaves, the other 26) member states. However, many British Eurosceptics believe the EU is a convenient cover for German ambitions. Germany can hide behind the EU’s multinational institutions, pretending to be a good European while behind the scenes it pulls the strings. Are we right to be concerned?

The most persuasive element in this argument is Germany’s membership of the Euro. The common European currency was bound to be far weaker than the mighty Deutschmark, making German exports artificially cheap. Other Euro members can’t devalue their currencies to make their exports cheaper, which gives German manufacturers a big advantage (Germany is the world’s third biggest exporter, after China and the US).

This fear has persisted in Britain ever since 1990, the year of German Reunification, when Thatcher’s Secretary of State for Industry, Nicholas Ridley, told The Spectator that European Monetary Union was ‘a German racket designed to take over the whole of Europe.’

Ridley was right about the outcome, but he was wrong about German motives. The Euro was not a German conspiracy to take over Europe. Rather, it was a French attempt to limit German power. Did France’s plan backfire? Well, yes and no. On the one hand, Germany is indeed now more dominant than ever. On the other hand, it’s hard to believe Germany would have been any weaker with the Deutschmark. The Deutschmark had become a monetary black hole, sucking every other European currency into its orbit. If Germany hadn’t joined the Euro, it might be even more powerful today.

The same could be said of a reunified German per se. Reunification made Germany a bigger country, but it didn’t make it any stronger – quite the opposite. Incorporating East Germany into the Bundesrepublik has been an immense drain on the German economy. It remains an immense drain today. If the Berlin Wall had remained standing, and East Germany had survived, the Bundesrepublik might carry even more clout, in a smaller, more cohesive EU.

And what would have become of East Germany if the Wall had remained standing? Its Communist government would still have crumbled, eventually, but instead of a bigger Bundesrepublik, with all the checks and balances that entails, we’d be stuck with a post-Communist state whose future remained uncertain – at best another Hungary, at worst another Ukraine.

I’ve been a regular visitor to Eastern Germany ever since the Wall came down, and witnessing the renaissance of this Communist wilderness has been the defining political experience of my life. Like a lot of British liberals raised during the Cold War, I was weaned on the notion that the United States was merely the lesser of two evils. The USSR was worse, but only a bit worse. When I went to Berlin, the scales fell from my eyes.

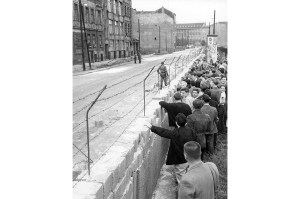

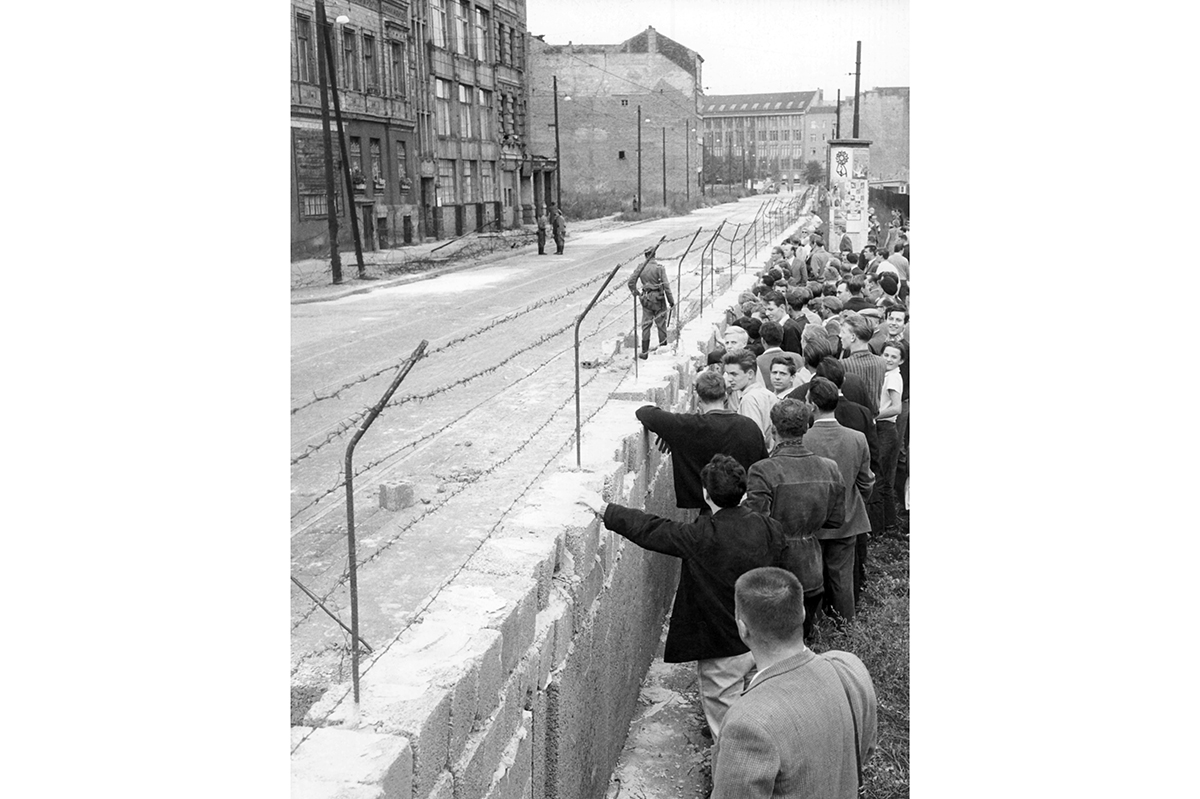

The postwar history of Germany was an extraordinary experiment on a monumental scale: take an entire country and divide it into capitalist and communist spheres; tie the Western half to the world’s capitalist superpower, the USA; tie the Eastern half to the world’s communist superpower, the USSR; wait forty years, then tear down the Wall. What are you left with? A booming economy in the West, with a dynamic political, artistic and intellectual culture, and a bankrupt tyranny in the East, which imprisons its own citizens behind an ‘anti-Fascist protection barrier’ (as East Germany called the border) and ferociously punishes even the slightest dissent.

The lesson of the Berlin Wall is that capitalism works, and is a force for good, and that the converse is true of state socialism. Once it became possible to incorporate East Germany into the Bundesrepublik by peaceful means, the ideological case became incontestable. For Western democrats, it wasn’t just a smart move – it was a moral duty. America led the way – not just during that momentous year, between the Mauerfall in 1989 and German Reunification in 1990, but throughout the Cold War, when the US kept West Berlin alive. If it hadn’t been for the USA, Germany would have been reunified forty years earlier, by the Soviets, and German economic power would be the least of our concerns.