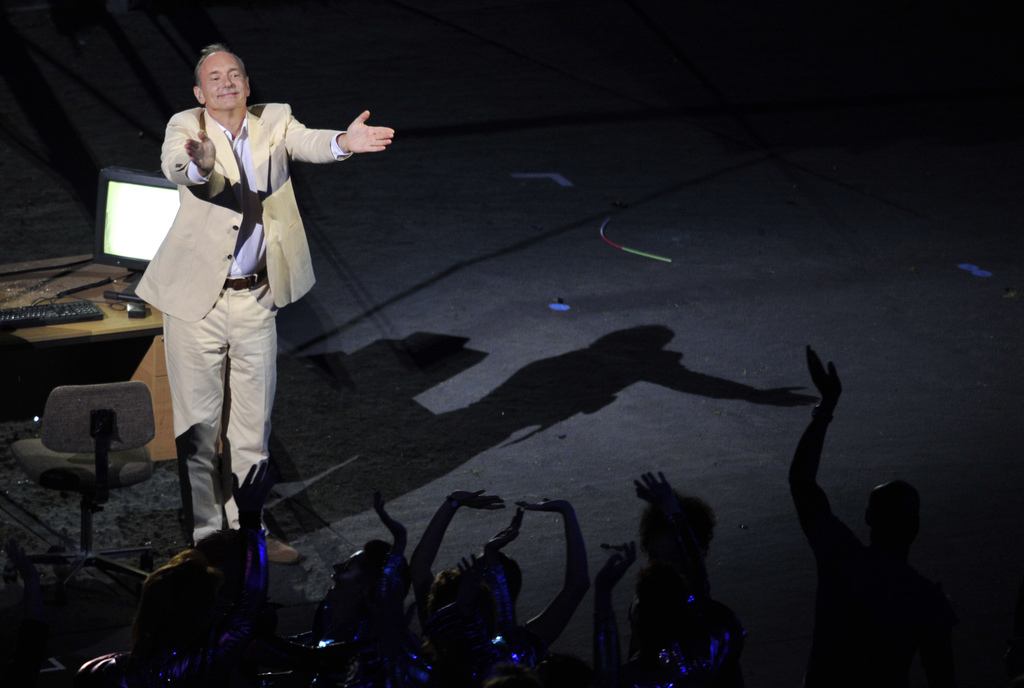

The World Wide Web is twenty-nine years’ old today, according to its Dr. Frankenstein, Sir Tim Berners-Lee. Or is that false news?

Sir Tim, like Frankenstein before the monster gets ideas of its own, is proud of his creation. In an open letter, a kind of philosophical birthday card, Berners-Lee notes that 2018 is ‘a milestone’ in the web’s history:

‘for the first time, we will cross the tipping point when more than half of the world’s population will be online’.

The next question, he believes, is how to get the other half connected. In 2016, the UN declared internet access ‘a human right, on par with clean water, electricity, shelter and food’. But without investment, the poorest billion will not be online until 2042. Yet again, us connected First Worlders are showing our casual cruelty towards those with no Second Life. We are depriving the compulsive masturbators of Malawi of their jollies. And how will the jihadists of Niger build their bombs if they can’t download the instructions courtesy of Google?

Berners-Lee wanted the Web to be a ‘free, open, creative space’. He has got what he wanted, good and hard. Like Dr. Frankenstein, Sir Tim now has mixed feelings about the inhuman freak show he has unleashed: ‘Are we sure the rest of the world wants to connect to the web we have today?’ It’s a tough question. Perhaps Facebook could organise a digital referendum, so we’ll know how to vote.

Berners-Lee was the first adult in the room of the Web, and he still seems to be the only one. To his credit, he is not afraid to name the culprits. The problem, he writes, is an imbalance between ‘the incentives of the tech sector’ and the needs of ‘users and society at large’. Today, a ‘handful of dominant platforms’ — the ‘Big Four’ of Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google — control ‘which ideas and opinions are seen and shared’. This ‘new set of gatekeepers’ are using their wealth and the ‘competitive advantage of their user data’ to ‘lock in their position by creating barriers for competitors’.

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 left the Web’s development to market forces. But market forces have created monopolies. The Big Four are more than ‘information services’. They are, in the revolting parlance of the day, ‘curating’ their idea of a desirable online environment.

Desirable for whom? The Web giants have supplanted the town meeting and the public square. They have proven themselves expert at monetising our preferences, but disgracefully lax about regulating the reliability of their political content. They have flooded our children’s smartphones with violent pornography. They are the jihadist’s friends, and they make money by disseminating every species of hatred.

Silicon Valley has become the head of the US economy, and it is wagging the tail in Washington, DC. The tech giants are sending a river of cash to Washington, and the ‘donations’ are working. In March 2017, the FCC reversed an Obama-era law forbidding companies to sell our browsing histories. Since 1996, administrations both Democratic and Republican have trusted the tech companies to regulate themselves. They have failed that trust.

We need, Berners-Lee writes, changes in the ‘legal or regulatory framework’. Berners-Lee does not say what those changes should be. But the first steps are obvious. Internet companies no longer need sheltering from laws and regulations. Rather, we need protection from their malign influence.

Web companies should be redefined in law as ‘common carriers’ like the telephone companies, and ‘publishers’ like the people who used to print books. Only then will they take responsibility for their content. In regulatory terms, we need the break up the tech monopolies. Like the railroad companies of the Gilded Age, the tech companies are trusts that need to be busted.

The tech companies, Berners-Lee writes, ‘have been built to maximise profit more than to maximise social good’. This is a polite way of saying that the Web is destroying the civil and rational discourse on which democracy depends. They are raising mobs. If they are not corrected by the hand of government, they will be corrected by the prod of the pitchfork.

‘Had I right, for my own benefit, to inflict this curse upon everlasting generations?’ Dr. Frankenstein asks in Mary Shelley’s novel. ‘I had before been moved by the sophisms of the being I had created; I had been struck senseless by his fiendish threats; but now, for the first time, the wickedness of my promise burst upon me; I shuddered to think that future ages might curse me as their pest…’