When I launched the original iteration of my company, Phetasy.com, in 2005, my vision was to provide some free content and some just for subscribers. I thought I could take the principles of the Wall Street Journal and the Grateful Dead and apply them to my own brand: WSJ was an early adopter of the hard paywall and the Dead pioneered giving early ticket access to their most loyal fans.

My vision bankrupted me. I should have sought out some investors or used other people’s money — but I couldn’t generate subscribers fast enough to keep up with the cost of maintaining and upgrading a website.

By 2016 I was writing for Playboy. I’d just landed in London and heard that my brilliant editor had been laid off midway through editing my column. That was my first hard lesson about jobs in media: they are not to be trusted. I filed my piece that morning; he was gone that night. I was in another country and my sole source of income was suddenly not so secure. Panicked, I realized I needed to diversify — and fast.

I’d recently heard about Patreon, a site that gives content creators the tools to run a subscription service. It was exactly what my original website was, only at scale, the perfect place for me. I’d grown my audience on Twitter and thought maybe a few people would subscribe, at least enough to provide some supplementary income.

Pretty soon my Patreon was making more money than my writing gigs. This afforded me the ability to speak my mind on left-wing insanity I was noticing that I might otherwise have self-censored for fear of losing my job. (I did ultimately lose that job — and it might have been for speaking my mind.) Either way, it didn’t matter. I’d protected myself: When it came time to launch my podcast Walk-Ins Welcome, I debated on whether to start on Patreon or go with the network, Ricochet, that had approached me. At that point, Patreon was banning creators and pulling the plug on them for dubious reasons. Having all my eggs in that basket made me nervous, so once again, I diversified. Ricochet was lovely to work with and they’re all great guys.

In 2019 podcast host Dave Rubin launched Locals in competition with Patreon and lured me onto his site with the promise of free speech and the cachet of being its first adopter. So I migrated, though I didn’t know enough to negotiate for some kind of compensation for bringing my Patreon followers over.

Locals’s later sale to Rumble taught me a lesson in this Wild West media space: capitalism always wins, and sometimes I’m the loser. It was frustrating to get behind a platform that I thought was all about independence and learning I was just a product.

Meanwhile Substack, another site that “combines a personal website, blog and email newsletter or podcast” was exploding as journalists and pundits like Glenn Greenwald and Bari Weiss pivoted from prestige institutions to build their own personal brands and media empires.

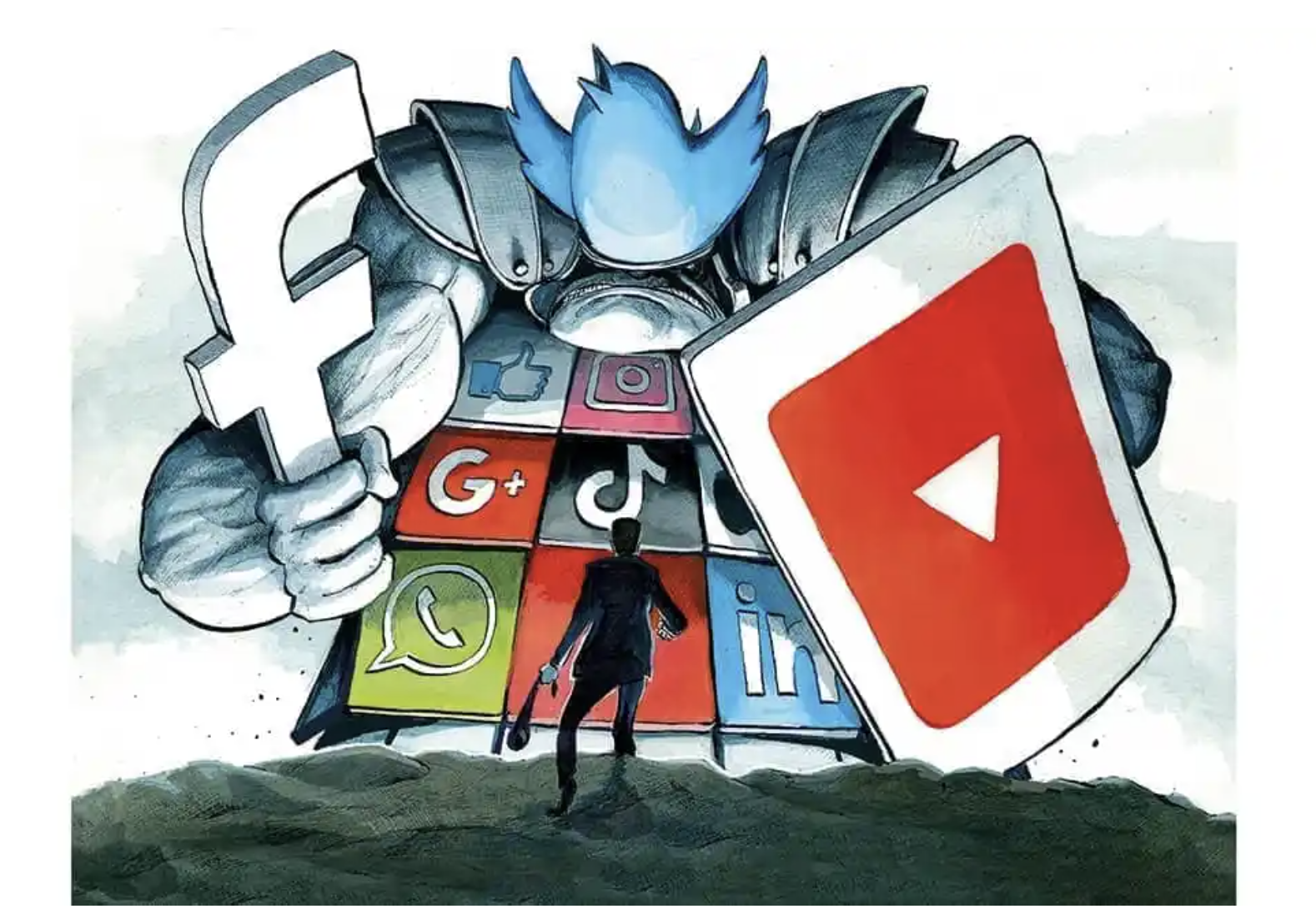

But the subscription model isn’t sustainable. How many $5 per month subscriptions can one person afford? In this economy? The disposable income people had when they were locked down is going back to the real world again. Concerts. Bars. Movies.

Subscription fatigue has long since set in: It’s not about the product, it’s about getting that subscription dollar. Smaller media outlets are competing with the big boys, like Netflix, Hulu, Disney+, the New York Times, YouTube… I could go on, but you know what I’m talking about from a quick glance at your bank statement.

So now there’s consolidation in the media space. Rumble gave massive deals to Greenwald and Russell Brand with the caveat that they use Locals. Bari has started her own outlet, the Free Press, and is attempting to acquire some smaller but vibrant podcasts and Substacks. The Daily Wire is trying to gobble up every profitable conservative for big money, as was clear during its very public, very nasty, ultimately unsuccessful fight with Steven Crowder, a mediocre pundit with a massive Facebook audience, over a deal that ultimately didn’t go through.

Where are we headed? Back to where we came from: bundling. Cable. And where does that leave me? People much smarter and wealthier have told me I need to put everything under one banner — consolidate — and they are probably right. Instead, I now have three podcasts, none of which are in the same place. I have a Substack and a presence on Locals. I have a show on YouTube that I also post to Rumble.

But I don’t like having all my eggs in one basket. It makes me anxious. Seeing media companies fold overnight and subscribers turn on writers because they don’t agree, and people get laid off in droves — there is really no easy way to navigate this space if you’re truly an independent creator.

So I’m back to 2005. I dream of my own website, where I can consolidate it all and control my own destiny. Or at the very least, wait to be acquired. In the meantime, subscribe to The Spectator World, I guess?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.