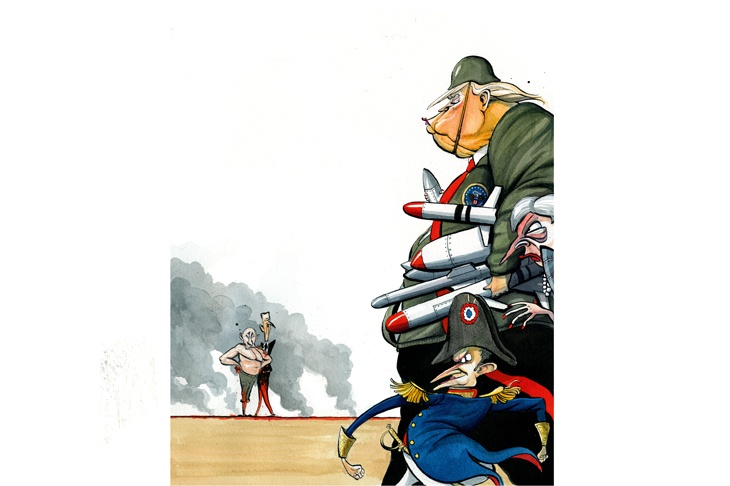

Happy now? The US-led air strikes against Syrian bases, notably chemical weapons storage facilities, near Damascus and Homs and reportedly elsewhere, has been, according to all the participants, American, Brits and French, a success. Or, as Donald Trump put it, ‘the nations of Britain, France, and the United States of America have marshalled their righteous power against barbarism and brutality’. Well that’s good, if you put it like that. Unrighteous power would have been quite another thing. And no one wants to see chemical weapons used in Syria or anywhere else, no?

Trouble is, the actual war in Syria will not be terribly affected by these air strikes, except, as Russian observers unhelpfully point out, to the extent that the Syrian army will be weakened in its operations against the rebels. And it is with the war itself, rather than the peripheral – and immoral – use of chemical weapons, with which we should be concerned.

Who do we actually want to win? Or are we prepared to say? The rebels who left the enclave of Douane – where the chemical weapons attack precipated last night’s air strikes – are, like those most pundits supported in Aleppo, a decidedly mixed bunch. Do we actually want them, and their actual backers, Turkey and Saudi Arabia, to take power in Syria. Really? Are we quite sure that the monster – Trump’s word – Assad, backed by the Iranians, wouldn’t be the less bad option, at least if he were forced to make necessary concessions?

The trouble with what passes for debate on all this in Britain, ever since the Commons debate on intervention in 2013, which was voted down thanks to Labour (Ed Miliband’s finest hour, if you ask me) is that we’ve been very big on the monstrous excesses of Assad, much less clear about what would actually happen if the rebel opposition were to win. And the notion that they would be preferable is the least examined but most pertinent question of all. The idea that they are in any sense liberal in our sense – except those who feature in international conferences abroad – does not bear much scrutiny.

As Patrick Cockburn, perhaps the best informed of British journalists on Syria, and who actually travels within the country rather than reporting from neighbouring states points out, ‘As early as August 2012, a report by the Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA), the Pentagon’s intelligence arm, stated that “the Salafists, the Muslim Brotherhood, and AQI [al-Qaeda in Iraq] are the major forces driving the insurgency in Syria”. It is worth reading in full the DIA report which forecasts “the possibility of establishing a declared or undeclared Salafist principality in eastern Syria”. This was two years before Isis declared the Islamic State.’

In other words, our end game in Syria – though Mrs May denies that this time, unlike 2013, we are actually in the business of regime change – would still appear to be to replace the present unsatisfactory regime with something like the state of Libya, where the removal of a dictator, courtesy of David Cameron et al, has worked out terribly well, hasn’t it?

What we actually must do, for once, is decide who we want to win, and on what terms. My view is that the least worst option is for Assad, rather than the Islamist rebels, to win militarily and for this to be followed by a negotiated peace settlement, involving the real players in the region – Saudis, Turks, Iranians – in which Russia would oblige him to accept the return of refugees and an eventual handover of power.

And in terms of that outcome, last night’s strikes were at best irrelevant. But admitting as much would require a degree of clear thinking that our political classes – possibly with the exception of Britain’s Jeremy Corbyn – do not appear to possess.

PS It’s gratifying that we take our obligations under the chemical weapons conventions so seriously. But we are also signatories to the Genocide Convention under which we are obliged to prevent and punish genocide wherever it takes place. But when IS carried out genocide against the Yazidis in 2014, partly as a result of the enfeeblement of the Iraqi Army which abandoned Mosul to IS, we were very much less quick to act…indeed, Raqqa only fell months ago. Yazidi girls were taken and traded as sex slaves, Yazidi men and older women massacred. But somehow, we were much less precipitate then, though there was a great deal we could have done at the time. Our interventionist impulses are curiously erratic don’t you think?