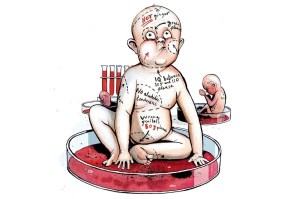

Earlier this month, a curious report caught my attention. Apparently there exists no rigorously established evidence that electric shock therapy, or ECT (electroconvulsive therapy), works. At all. In Electroconvulsive Therapy for Depression: A Review of the Quality of ECT versus Sham ECT Trials and Meta-Analyses, Dr John Read, Prof Irving Kirsch and Dr Laura McGrath have shown that the therapy, commonly administered for severe depression, has not (despite claims) been shown to have any significant positive effect, ever. It can be dangerous, carrying a small risk of death and a higher risk of serious memory loss, yet (the authors say) more than a million people worldwide are undergoing this therapy today, for no proven benefit.

I doubt I ever thought otherwise, and nor perhaps did you. I’d have labeled ECT as quack medicine, but had no idea how prevalent — even popular — it is, nor how widely it is believed in. I agree with the authors that it should not be prescribed. Perhaps it should be outlawed.

The report, however, set my mind on a different track. Why are people so receptive to the claim that a big electric shock could jolt you out of mental illness? There is something inherently attractive in the idea: a way of thinking exemplified by a phrase my father used when any of us, his children, were being moody, grumpy or unhelpful. ‘Snap out of it,’ Dad used to say.

You know immediately what he meant. Actually, in a day-to-day way, if not for clinical mental illness, you’ll know too that the approach often works. We’re all prone to overthink, to let a problem ‘get on top of us’, to ‘get it out of proportion’, to get stuck in a negative groove; and we do know that dropping the preoccupation completely and switching our attention to something else can make it possible to return later and see things in perspective.

It was the Victorians who popularized early versions of ECT. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries you could buy little electric-shock kits (a friend once gave me one) beautifully made in polished wood and supplied with either a battery or a winder-generator. You attached electrodes to yourself, flipped a switch, and crack — anyone who has ever brushed an electric fence or gripped the lead to a car’s spark plugs will know the feeling. Because my own imagination works like this I can easily understand why one might think the effect therapeutic. In university days when I drank too much I would jump into a freezing shower before bed in the (only semi-coherent) belief that the shock would sober me up, blow away the hangover. That it hurt only boosted the supposed logic; I was punishing myself — as Gladstone used to with a self-administered whipping after he had talked to prostitutes and become aware of bad thoughts while he was with them. He marked these in his diary with the sign of a whip. A good smack, we half-think, does more than deter; it can shock a person out of a bad frame of mind.

Or so humanity has always believed. And I think humanity is right. I’ve just finished working through the publisher’s proofs of my book Fracture, based on my BBC radio series, Great Lives. After genning myself up (over 16 years) on more than 300 lives of extraordinary men and women, I’ve observed how often trauma, among whose variants shock stands out, has been a feature of the individual’s younger years. So very often, something has been broken, and the fracture has released the person from the ordinary. It took the freezing water of the Seine, into which the wildly imaginative artist and sculptor Louise Bourgeois had jumped in a suicide attempt on the death of her mother, to jolt her out of mathematics and into art. It took a near-death attack of epilepsy that shocked Machado de Assis, a Brazilian pulp fiction writer, out of profitable pap and into his place as arguably the greatest novelist in the Portuguese language.

***

Get a print and digital subscription to The Spectator.

Try a month free, then just $7.99 a month

***

Not only can shock reset, jump-start, re-make a life, I think that half-unconsciously humanity has always known this. You see it again and again in children’s stories, in myth and in religion. St Paul, struck blind on the road to Damascus; the Prophet Muhammad losing his mother, father, then beloved guardian uncle as a child; St Patrick, carried off into slavery; Dorothy, wrenched by a tornado from grayness and sorrow into color and adventure. Alice, falling, falling, down that infinite rabbit hole. Fiction or fact, these are the tales people remember and pass down. Shock is so reliably central to the plot: and shock’s effect, typically, transfigures.

You thought, perhaps, we could finish this Spectator page without COVID-19. Apologies, but as (hopefully) we awake to a post-lockdown world, heads still spinning, I wonder whether this could be a time of recalibration? I wonder whether having been forced to take three paces back from our lives, and see ourselves and our daily grind from a distance, the result might prove a more successful variant of electroconvulsive therapy? Collectively, we’ve had a sort of out-of-body experience — looked at our lives and our preoccupations from outside. As a slap in the face can sometimes be a remedy for hysterics, so 21st-century humanity has received such a slap; and it’s possible to hope we will emerge from this strange time calmer — in some deep way — than we went into it.

I said ‘hope’. I’m hardly confident. It’s more likely we’ll indulge ourselves for a while in pieties about rebirth, reset and re-imagine, but then revert to our bad old ways: running ourselves ragged again, destroying our planet again, seeking again what divides rather than unites us. But let me dream. Clever-clogs analysts of political behavior like to talk of the ‘dead cat’ tactic: plonking a feline corpse on the committee-room table as a way of changing the subject. Might COVID-19 have changed the subject too? If so, that little virus could prove the dead cat of the century.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.