Japanese Emperor Naruhito was formally enthroned this week, in the second of three major ceremonies marking his accession to the Chrysanthemum Throne. As Brexit chaos continues to paralyze Britain, impeachment roils American politics, and months of anti-China protests rock Hong Kong and flummox Beijing, Japan again offers an example of political and social stability regularly overlooked. Even as the country recovers from a devastating super typhoon, it celebrates a new sovereign whose era name, Reiwa (Beautiful Harmony), is undoubtedly the envy of other great powers being tested at home and abroad. Some of Japan’s stability may well come from the symbolic role the imperial family plays and its conscious appeal to the past.

The emperor succeeded his father, Akihito, in May, after the first imperial abdication in over two centuries in the world’s oldest monarchy. Akihito’s decision was precipitated by poor health, yet after his three decades of faultless service on the throne, there were no serious movements calling the imperial family an anachronism in the 21st century or demanding an end to the monarchy. Instead, Naruhito on May 1 seamlessly received two of the three imperial regalia, an ancient sword and jewel, as well as the seals of state, in the first of the accession ceremonies, held in the Imperial Palace. All told, 52 separate rituals will be performed through April 2020, many of them created specifically for the unprecedented abdication.

On Tuesday, Emperor Naruhito participated in a day’s worth of ceremonies, seen only once in the past 93 years, when his father was enthroned in 1990. The streets of downtown Tokyo were closed to traffic as the emperor and empress rode to and from various palaces, though a public parade was postponed in the aftermath of the typhoon. The ceremonies started with a morning private ritual at three sacred shrines inside the Imperial Palace precincts, where, garbed in pure white court robes based on 8th-century models, Naruhito informed the Japanese gods of his accession. In the afternoon, as nobility and dignitaries from 180 countries watched, including US transportation secretary Elaine Chao and Britain’s Prince Charles, the drapes of the 21-foot-high, 8-ton Takamikura (High Seat), topped by a golden phoenix, opened to reveal the emperor, this time in golden court robes, who publicly announced his enthronement. Next to him, on a smaller throne, Empress Masako appeared in even more elaborate court dress, wearing a 12-layer kimono. Next month, the emperor alone will personally offer food to the Sun Goddess Amaterasu, in a mysterious nighttime ritual called the Daijosai (Great Harvest Ceremony), the most sacred of the enthronement acts.

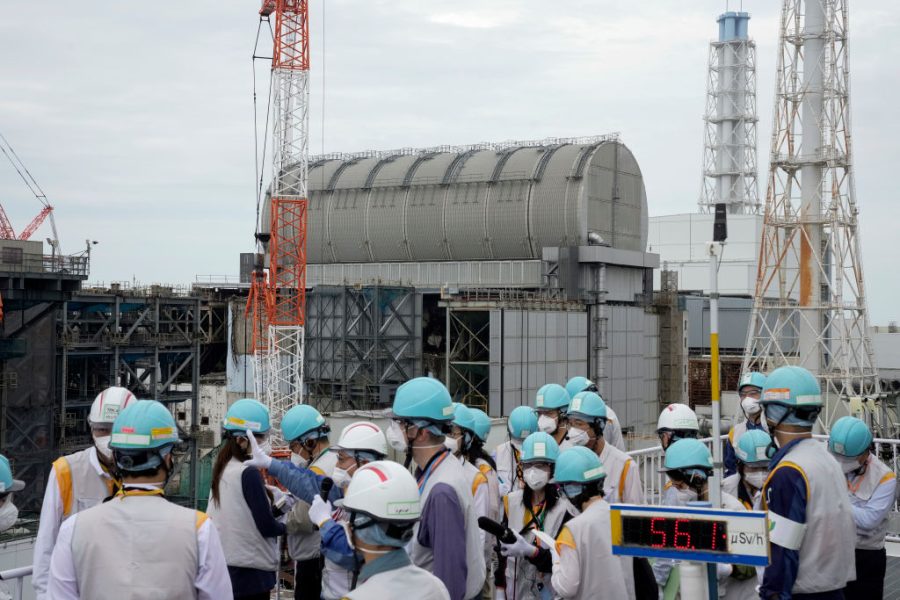

The impression of eternal immutability these ceremonies provide belie the fact that under its placid surface, Japan faces daunting challenges. It never fully recovered from the popping of its asset bubble at the very end of the 1980s, and many of its companies have not recaptured their competitiveness. It has been eclipsed by China, especially in cutting-edge technology such as artificial intelligence; its grim demographic picture — the country recorded the sharpest drop in births in 30 years last year — clouds its future economic possibilities; it has a nuclear-armed North Korea to worry about; poverty measures are rising; and it is facing headwinds from the US-China trade war. Nor were prior decades free from social trauma: Massive demonstrations erupted during the 1960s over foreign affairs and domestic politics while homegrown terrorists struck in the 1970s and 1990s, including with the infamous sarin gas attack in Tokyo in 1995.

Since the collapse of Japan’s economic miracle 30 years ago, the world has largely ignored the country, focusing instead on China’s rise. Yet when Prime Minister Shinzo Abe congratulated the emperor in front of the imperial throne Tuesday, he did so during Japan’s most stable political period in decades; indeed, Abe is now the second-longest-serving premier in the postwar period, having returned to office in December 2012 after a previous one-year stint. Abe has forced through a raft of economic reforms designed to shake up the sluggish economy through regulatory reform, changes to land ownership, liberalizing the energy market and encouraging female labor participation.

Abe has worked steadily to improve Japan’s international standing, deepening relations particularly with India, Australia and Southeast Asia. He has also increased defense spending each year in the face of Chinese and North Korean threats, giving Japan one of the most capable military forces in the world; the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force has been larger than the Royal Navy for a decade, albeit without the nuclear submarines. Abe has spent an enormous amount of time cultivating personal relations with Donald Trump and is seen as one of his closest allies.

While the ultimate success of Abe’s policies remains uncertain, Japan’s slow growth since the 1990s obscures its continuing top rankings in global health measures and educational achievement, as well as its high per capita GDP. Its politics are not poisoned by Twitter or cable television, and it remains astonishingly crime-free. Its populace seems comfortable with what is largely a one-party democracy, giving the ruling Liberal Democratic Party a near-supermajority in the national Diet. And as the citizens’ response to super typhoon Hagibis showed, a powerful communal sense remains, as it did after the devastating 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

Perhaps some of Japan’s social stability can be attributed to the imperial family. Unlike the scandal-ridden royals of other countries, members of the Japanese monarchy are models of propriety. Tainted by charges of war crimes during the 1940s under Emperor Hirohito, the new emperor’s grandfather, the postwar imperial family has eschewed even the hint of politics, focusing instead on higher education and uncontroversial patronage of social institutions. And in handing over power to his son, Emeritus Emperor Akihito may have sent a subtle message about how a rapidly aging Japan can maintain its traditions while flexibly responding to current conditions.

Just as important, the family has changed with the times. The emperor studied for several years at Oxford in the 1980s while the empress was educated at Harvard and was a rising young diplomat before exchanging her briefcase for white gloves and pillbox hats. Both she and her mother-in-law, the empress emerita, were born commoners, as was her sister-in-law, whose 13-year old son is second in line of succession (the emperor and empress have only one child, a daughter, who is not eligible to succeed to the throne).

And yet for all their adaptations to modern life, the emperor and his extended family provide a seemingly unchanging reference to Japan’s indigenous religion and ancient traditions. In a postmodern world racked by eternal impermanence, the symbolic role of Japan’s imperial family may add an indefinable ingredient to the material achievements of the postwar Japanese state. With a sea of democracies seemingly tearing themselves apart, perhaps that role, as imagined as it is real, is more important than ever.

Michael Auslin is the Payson J. Treat Distinguished Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford, and a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute.