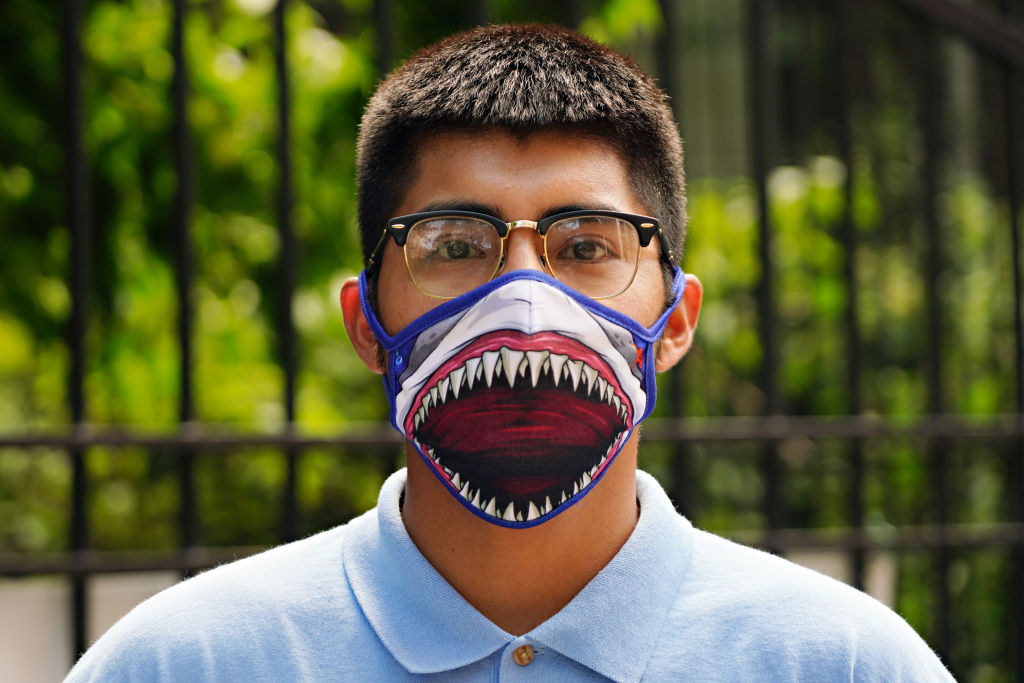

The increasingly polarized and politicised views on whether to wear masks in public during the current COVID-19 crisis hides a bitter truth on the state of contemporary research and the value we pose on clinical evidence to guide our decisions.

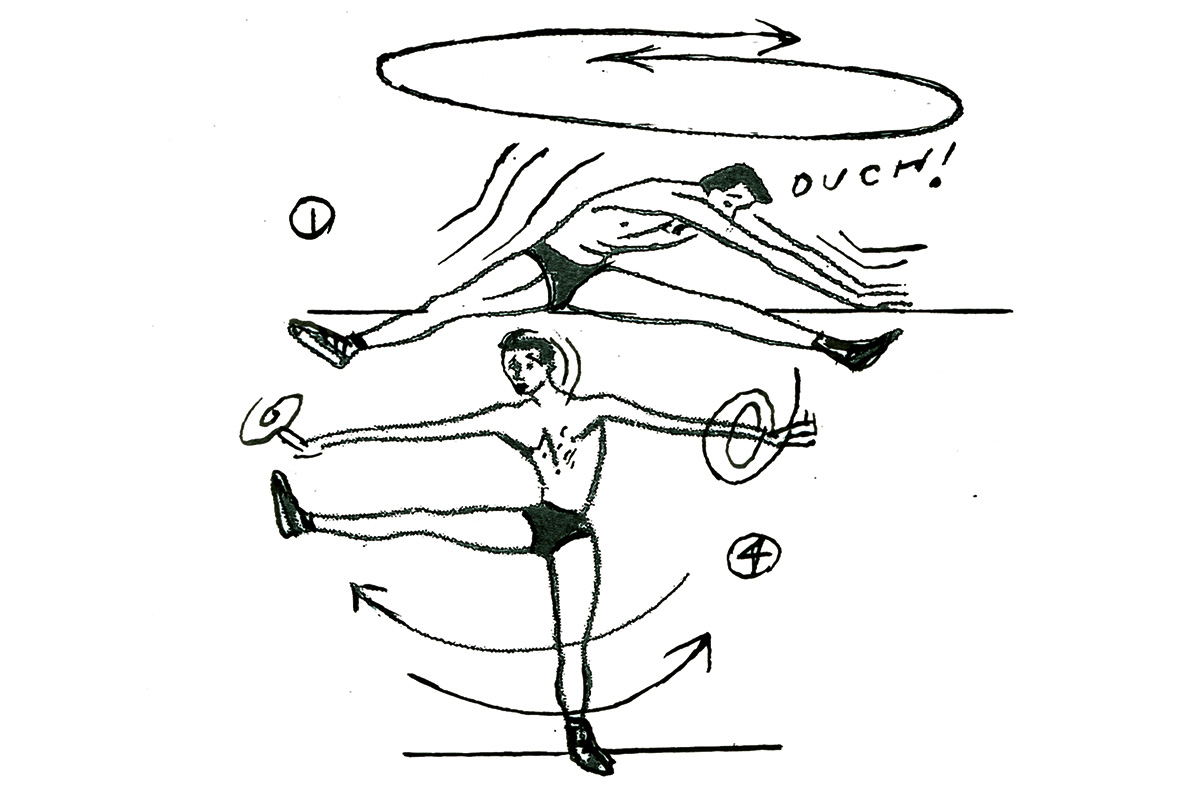

In 2010, at the end of the last influenza pandemic, there were six published randomized controlled trials with 4,147 participants focusing on the benefits of different types of masks. Two looked at healthcare workers and four at family or student clusters. The face mask trials for influenza-like illness (ILI) reported poor compliance, rarely reported harms and revealed the pressing need for future trials.

Despite the clear requirement to carry out further large, pragmatic trials a decade later, only six had been published: five in healthcare workers and one in pilgrims. This recent crop of trials added 9,112 participants to the total randomized denominator of 13,259 and showed that masks alone have no significant effect in interrupting the spread of ILI or influenza in the general population, nor in healthcare workers.

The design of these 12 trials differed: viral circulation was usually variable; none were conducted during a pandemic. Outcomes were defined and reported in seven different ways, making comparison difficult. It is debatable whether any of these results could be applied to the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Only one randomized trial included cloth masks. This trial found ILI rates were 13 times higher in Vietnamese hospital workers allocated cloth masks compared to medical/surgical masks, and over three times higher when compared to no masks.

It would appear that despite two decades of pandemic preparedness, there is considerable uncertainty as to the value of wearing masks. For instance, high rates of infection with cloth masks could be due to harms caused by cloth masks, or the benefits of medical masks. The numerous systematic reviews that have been recently published all include the same evidence base, so unsurprisingly reach broadly the same conclusions. However, recent reviews using lower quality evidence found masks to be effective, whilst also recommending robust randomized trials to inform the evidence for these interventions

Many countries have gone onto mandate masks for the public in various settings. Several others — Denmark, and Norway — generally do not. Norway’s Institute for Public Health reported that if masks did work then any difference in infection rates would be small when infection rates are low: assuming 20 percent asymptomatics and a risk reduction of 40 percent for wearing masks, 200,000 people would need to wear one to prevent one new infection per week.

***

Get a digital subscription to The Spectator.

Try a month free, then just $3.99 a month

***

What do scientists do in the face of uncertainty on the value of global interventions? Usually, they seek an answer with adequately designed and swiftly implemented clinical studies, as has been partly achieved with pharmaceuticals. We consider it unwise to infer causation based on regional geographical observations as several proponents of masks have done. Spikes in cases can easily refute correlations, compliance with masks and other measures is often variable, and confounders cannot be accounted for in such observational research.

A search of the COVID trials tracker reveals nine registered trials of which five are currently recruiting participants and one enrolling participants by invitation. In Denmark, where masks are advised for those who break self-isolation to go out to take a test, a randomized trial including 6,000 participants is assessing reductions in COVID-19 infection using surgical facial masks outside the healthcare system. In Guinea-Bissau in West Africa, the Bandim Health Project is leading a 66,000 person trial — although not yet recruiting — on cloth face masks.

The small number of trials and lateness in the pandemic cycle is unlikely to give us reasonably clear answers and guide decision-makers. This abandonment of the scientific modus operandi and lack of foresight has left the field wide open for the play of opinions, radical views and political influence.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.