A historian should feel a strong sense of déjà vu on reading about Prince Harry’s rebellion against his family. Rebellious “spares” are a constant feature of English history since at least 1066. Simon Sebag Montefiore’s characteristically vivid new book The World: A Family History offers plenty of gory examples from ancient Egypt, medieval China and even, when we move away from royalty, within dynasties such as the Kennedys. While the Byzantine emperors preferred to poke out the eyes of family members who competed for power, the Ottoman sultans regularly had their brothers strangled within hours of acceding to the throne. North Korea, where Kim Jong-un appears to have disposed of his half-brother by having him poisoned at Kuala Lumpur airport, is a recent example of lethal sibling rivalry within a ruling dynasty.

Turbulent princes might but presumably will not turn to the Bible. A constant refrain there is the way younger sons supplant elder brothers. These stories were probably tailored to justify the seizure of the ancient throne of Jerusalem by younger sons. The Bible describes how King David (himself a youngest son) chose Solomon as his heir, unaware that another son, Adonijah, had already tried to seize the throne from his dying father and his much younger brother. The theme of younger brothers gaining not just human but divine preference is there in the story of Jacob and Esau, even if Jacob was younger than his twin only by a matter of minutes. The worst case of sibling rivalry, the sale of Joseph into slavery by his jealous brothers, culminated in their humiliation when they appeared as supplicants in front of their unrecognised brother, now the Pharaoh’s vizier in the greatest empire on Earth.

Primogeniture is not entirely to blame for resentment on the part of younger princes. Elective monarchies too have had their share of sibling conflict. The great assemblies at which the Mongols elected their supreme leader generated rather than suppressed sibling rivalry. Mongol law required the youngest son to take charge of the family’s lands, while his brothers fanned out across the vast Eurasian spaces that had already been conquered, fracturing the empire into what became competing states. But there have been imaginative solutions to the problem of succession. In Sumatra, the early medieval kingdom of Srivijaya controlled the prosperous trade routes leading into the South China Sea. At court ceremonies the king was expected to wear a very heavy crown adorned with hundreds of jewels, and the succession was decided by choosing from among his sons the one who could bear its weight on his head. If tried here, my guess is that Prince Andrew, the burliest of the late Queen’s sons, would have lasted longest under the five-pound weight of St. Edward’s Crown.

Prince Harry is open about his resentment at being number two. In medieval Europe there were imaginative but strikingly unsuccessful ways of addressing sibling jealousy. Lands recently acquired by conquest were often seen as disposable. William the Conqueror provides one of the best examples. The rivalry among his sons Robert, William and Henry, and the Conqueror’s sense that the true patrimony of his family lay not in England but in Normandy, led him to confer his Duchy of Normandy on his eldest son, and to grant William Rufus England and the royal title. This left Henry hungry for a share in the proceeds — everything resolved itself nicely for him when Rufus was shot by accident in the New Forest, and within hours Henry I had seized power.

The Christian kings in medieval Spain had for centuries tried to deter in-fighting between royal princes by dividing up their kingdoms in their will. Even so, this tended to set off fighting between Christian princes that was more bitter than their famous battles against the Muslim rulers of southern Spain. The will of King James I of Aragon deprived his ambitious elder son Peter of the newly conquered island of Majorca as well as the area around Perpignan, the ancestral lands of their Catalan dynasty, all of which was granted to his younger brother James as a separate kingdom. Peter grudgingly promised his father that he would live in harmony with James after their accession. But in 1283 Peter took advantage of a wider war for control of Sicily in which they stood on opposing sides. Peter hunted down James in the Palace of the Kings of Majorca that still stands in Perpignan. As Peter hammered on the door, James barricaded himself in his bedroom, insisting he was suffering from flu, and then fled through a sewer under the floor — an undignified and messy escape.

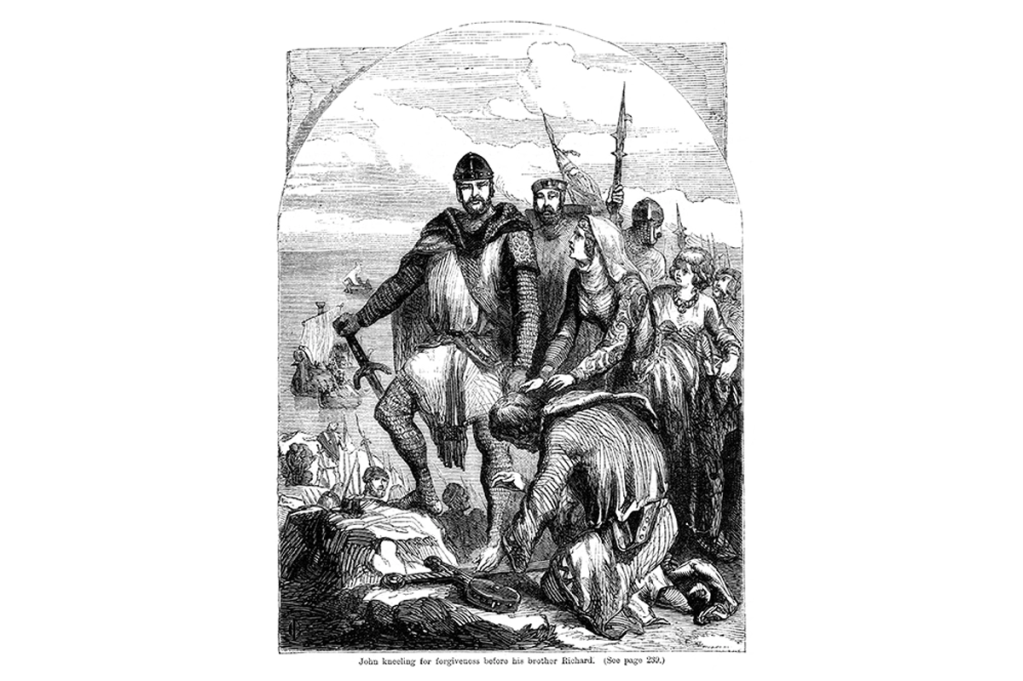

Keeping an eye on younger brothers was essential. Among the four sons of King Henry II of England, intense rivalry erupted into armed conflict between the eldest, also named Henry, and the immediate “spare,” Richard. Then, after Henry predeceased his father, Richard faced the unbridled ambition of the new spare, John, whose fits of anger sometimes had him rolling on the floor in fury. Later, King Edward IV failed to foresee that his scheming brother Richard would declare Edward’s children bastards and seize the Crown for himself.

Rather different, though, is the case of Edward VIII. Albert, Duke of York, had no ambition to supplant his elder brother, but after the abdication the envy went in the other direction: for several years the Duke of Windsor seems to have hoped for his restoration, even if it would be at the hands of Nazi allies. And, as nowadays, what he saw as ill-treatment of his wife sharpened his pain.

What is so very different now is that it is possible to harness the world’s media in just about every form. The new weapons are the press, television (notably Netflix), Twitter and book sales: better obviously than Richard or John taking up arms, but also very risky. At least there is no danger of the loser being locked up in the Tower.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.