A new king of the Zulu was crowned at the weekend. Thousands in South Africa went to Durban to watch the coronation of Misuzulu kaZwelithini. The city was sunny, which meant the Zulu ancestors were happy.

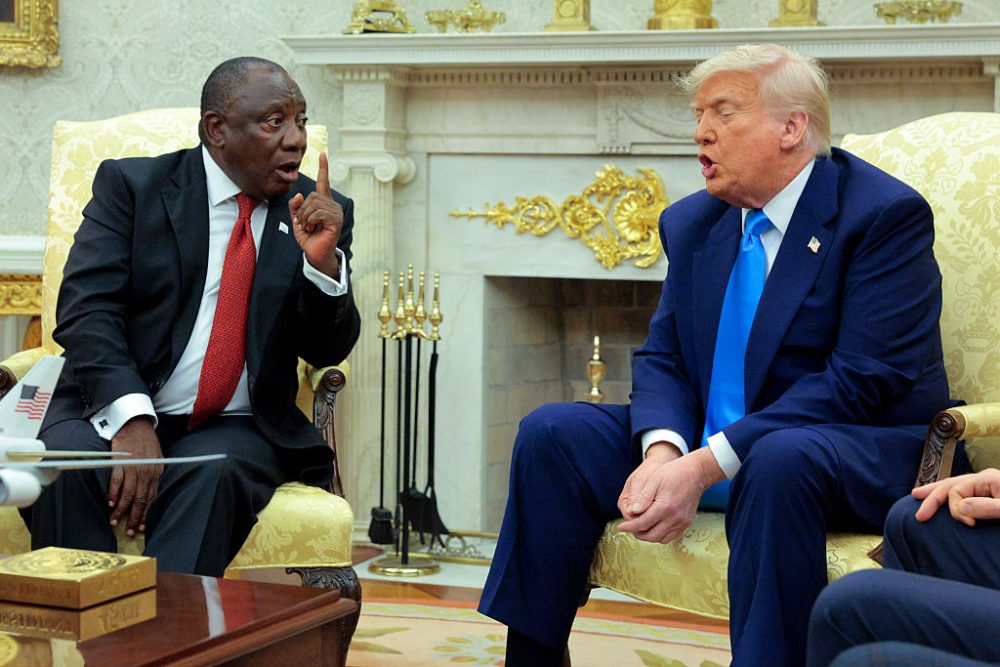

The coronation, held at the Moses Mabhida stadium, was a celebration of Zulu tribal dominance. While South Africa’s president, Cyril Ramaphosa, who handed over the certificate recognizing Misuzulu as the Zulu monarch, was booed by the audience, his predecessor, Jacob Zuma, was cheered. Ramaphosa comes from the tiny Venda tribe, on the border with Zimbabwe. Zuma is a Zulu.

Zulus don’t care much about the accusations against their former president. His opponents say he’s corrupt and used the president’s office for “state capture”: handing control of parts of the government to allies who robbed the treasury. To his people, the overwhelming evidence against him is irrelevant. He is one of their own, and the matter is tribal. The word Zulu means “heaven” and its 11 million people see themselves as chosen.

Most of South Africa’s tribal strongholds were set by wars. Durban is the biggest city in the Zulu majority province of KwaZulu-Natal, something of a homeland for the tribe. The province conforms roughly to the area conquered by Shaka, the first Zulu king, in the early 1800s. Further north, King Mzilikazi of the amaNdebele and General Gaza of the Tsonga, both having fled Zululand after fallouts with Shaka, conquered land too. They subjugated other tribes to the north and to the west of what is now Johannesburg.

The disputes read like a Shakespeare play. Intrigue and betrayal. Revenge. Shaka, paranoid about being overthrown, was murdered in 1828 by his half-brother, Dingaan. Mzilikazi ended up in Bulawayo, a city in what is now Zimbabwe, where his regiments slaughtered the local Shona people. On their way north to Bulawayo, Mzilikazi wiped out entire tribes and forced others into retreat. Gaza and Dingaan did the same, followed by the whites, both of English and Afrikaans descent, drawing the boundaries where today we find the Sotho, Tswana, Pedi, Xhosa, Tsonga and Venda tribes. From 1948 to 1994, the system of apartheid, with its forced removal of black people from what were deemed “white” areas, formalized these tribal homelands.

In towns and cities, these boundaries matter less — most black South Africans speak four or five languages and mix easily — but there are still tensions. In a beerhall you’ll still find the Pedi, Tsonga, Venda, Xhosa, Tswana and Zulu all in different huddles, and they’ll come together to talk soccer or politics. Sport unifies. In July last year, when Zuma was briefly imprisoned, his Zulu supporters rampaged across his stronghold in the east of the country. They burned down shopping centers and left 324 dead. The damage was estimated at more than $1 billion.

Tribal troubles didn’t matter this weekend. Not long after midnight on Friday, well before the sun rose over the Indian Ocean, Zulus were readying themselves to go to the Moses Mabhida stadium, where the crowning was held, while the millions who couldn’t attend held parties at home having spent weeks brewing their traditional umqombothi beer.

South Africa hasn’t been a monarchy since 1961. Back then it was a dominion like Canada or Australia, with the late Queen Elizabeth II as head of state. But there was a regal splendor to Saturday’s coronation. The Zulu king’s prime minister, and one of Africa’s great political survivors, Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi, was there, aged ninety-four. Heads of state, ambassadors and members of the central government from Pretoria also went. There are a dozen other tribal kings and queens across the country. None can put on a show like the Zulu.

The coronation was so fervent, partly because the succession has been so fraught. When King Misuzulu’s father, Goodwill Zwelithini, died in March last year, he left twenty-eight children and six wives. King Goodwill named Misuzulu his successor in his will, but his other children challenged the decision in the South African courts. By Saturday, most Zulus likely didn’t care which of the late king’s children sat on the throne. It was time for a new man to lead the tribe that held off the British at Rorke’s Drift and defeated them at Isandlwana.

King Misuzulu will become South Africa’s biggest land-owner, holding vast territories where his people live. But, like his father, he will have no political power and can’t fix the country’s most open wound: while official figures put unemployment at 34 percent, private research suggests the numbers are far higher for black youth, especially those under thirty. Many sell goods by the roadside but will tell you this is just to get by while they look for a job. As another school year ends, thousands more rural kids will head to the city in search of a better life. Few will find it.

What’s more, a third of the population are now squashed into a sixty-mile strip in the north of South Africa that includes the largest city, Johannesburg, and the capital, Pretoria. Last year’s riots were less about Jacob Zuma going to jail and more do to with the pain and anger that comes with living three or four to a shack the size of a bathroom, with no running water and perhaps one part-time job in the family.

Those troubles, too, were forgotten on Saturday. For that day, at least, Africa’s warrior tribe were in heaven.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.