The British newspaper the Guardian is worshiping at the shrine to its own piety with even more self-satisfaction than usual because it is paying millions in reparations to African Americans based in Georgia and Jamaica, whose slave labor 200 years ago underpinned the wealth of the newspaper’s founders. But where is the justice in that?

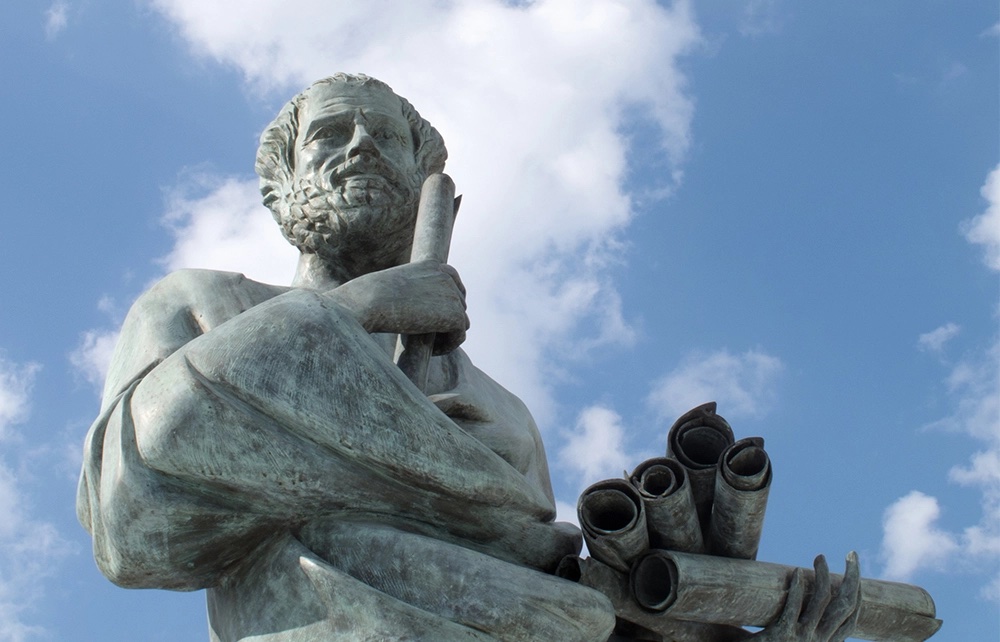

Aristotle argued that justice, which was good, depended on a form of equality. So for him, injustice was a matter of a man’s doing something wrong for his own advantage, thereby gaining an unequal share of something good. This could arise from (for example) buying and selling, “when quarrels arise when equals get unequal shares.” That was why money was invented, thought Aristotle, to solve problems that arose from such situations (e.g., in trying to work out “the number of shoes that are worth a house”) “since it makes goods commensurate and equalizes them.” It was all a matter of proportion, and the function of a judge was to try to restore equality between all parties involved in any disputes.

Aristotle was also aware that alongside justice there was such a thing as “equity.” This was called into play as a corrective when the “abstract formulations” of universal law were not able to deal with special situations, created by “the stuff of human conduct.” He came up with a delightful image of the ruler made of lead used by architects from Lesbos: “It is not rigid but molds itself to the shape of the stone,” like “a decree adapting itself to the facts of the case.”

Given the vast profits of the Guardian’s original owners, there is no “equal proportion” in the paper’s miserly millions. Nor is it even equitable, since there is no law which says that an organization, innocent of actions relating to events 200 years ago, should now be liable to compensate those who claim those events have affected them.

That leaves a question. Slavery is still with us, and the Guardian prides itself on its desire to end it. Was giving millions to Americans living in Georgia the best way to demonstrate their campaigning fervor?

This article is taken from The Spectator’s June 2023 World edition.