There was a time in the not-so-distant past when Europe and Russia had a mutually beneficial relationship with each other — at least in the energy field. Europe, a major oil consumer, received reliable supplies of crude and natural gas from Moscow, while the Russians received tens of billions of dollars in return. The European Union imported 155 billion cubic meters of natural gas from Russia last year, equivalent to about 45 percent of its total gas imports. There was an ingrained assumption in European capitals that, even if relations with the Russians were thorny, fossil fuels would continue to head west.

War, however, can change things in a flash. European and Russian officials now talk past each other, and sometimes they leave the room when the other is speaking. Russia’s five-month-old invasion of Ukraine is seen across the continent as an unforgivable crime of aggression in a world that is supposed to run on international law, humanity, and decency. From Russia’s vantage point, Europe is merely a lackey of the United States, less a sovereign entity than a servant taking orders. As Russian bombs fall on Ukraine, European military equipment is flowing into the hands of Ukrainian troops.

So we shouldn’t be surprised if Russian President Vladimir Putin chooses to upend the energy ties that served Russia and Europe so well. In April, Poland and the Czech Republic saw their imports of Russian gas stop completely. In June, Russia cut natural gas flows to Italy and Slovakia by roughly half, forcing both countries to scramble for alternate supplies. And on July 11, gas flowing through the Russia-to-Germany Nord Stream pipeline stopped for a 10-day period of maintenance work.

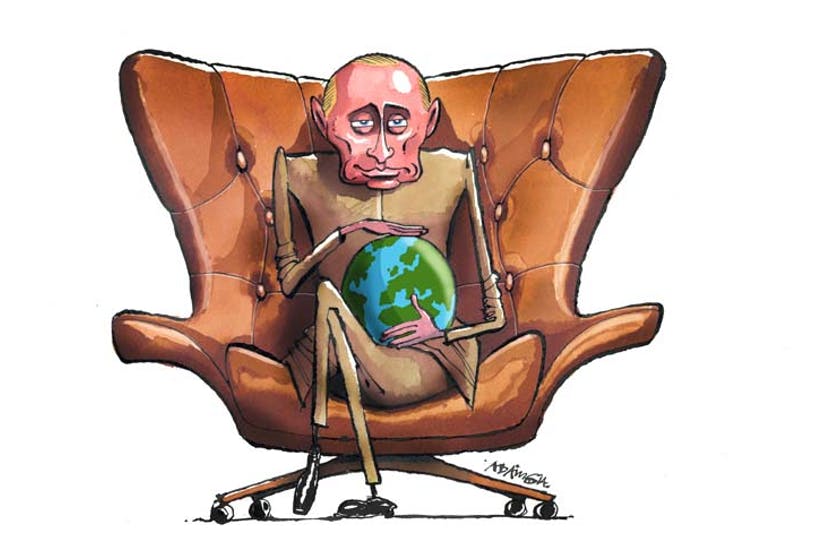

That 10-day clock is almost over — and the question is whether Moscow will resume pumping at the same rate. There are tremendous concerns that Putin, in his attempt to weaken European support for Ukraine, will decrease the gas flow through Nord Stream or shutter it entirely. The EU is taking both scenarios extremely seriously, as they should. French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire told an economic conference this month that a total Russian gas cutoff “is the most likely option.” Germany, a focal transit point for Russian gas entering the European market, has declared a “gas crisis.” Citi Bank assesses that Europe’s economic growth will not only stagnate, but lose as much as 2.6 percent from its GDP.

Europe’s reliance on Russia as an energy source is well known. While Germany has reduced imports of Russian natural gas since the war in Ukraine began, Russia still accounts for 35 percent of German supply. For Austria, the number goes up to 80 percent. This dependency provides Moscow with a considerable amount of leverage. The Europeans know this, even if it took the continent’s worst war in nearly 80 years to prod them into diversifying.

Now, Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi is visiting Algeria to finalize a natural gas deal, while the European Commission signed a deal with Azerbaijan on Monday to double EU imports of Azeri gas by 2027. Germany, Italy, Belgium, and France are also in talks with Qatar to boost gas imports. All of this is necessary given the stranglehold the Russians have on EU energy supplies (although the Europeans are surely cursing themselves for waiting so long).

Would Russia really take such a dramatic step? Maybe, maybe not. But Europe can’t afford to bury its head in the sand and hope for the best.

For the Russians, the benefits of such a decision are obvious. Putin, who has made his displeasure about NATO military support for Ukraine clear, isn’t going to retaliate militarily and start bombing NATO territory. While he may gripe about the EU’s restrictions on Kaliningrad, it’s unlikely Putin will pick a fight over the exclave when most of Russia’s active combat power is tied up in Ukraine. Russian sanctions against the West would be merely symbolic. Cyber operations against European infrastructure are possible, but Putin can’t be sure to what extent the US and Europe would retaliate.

Shutting the gas taps is thus the one lever the Kremlin has at its disposal. It would have an immediate negative impact on European supply, spike the price of fuel across the continent, lead to a cold winter as European governments enact strict conservation measures, and possibly increase division in the bloc, with European powers jockeying over supply. More importantly, from Russia’s perspective, a gas stoppage could undermine the unity that currently exists in the West on Ukraine.

There are costs for Russia as well. Using energy as a political weapon would only exacerbate the trend in Europe away from the Russian fossil fuel industry, and could even lead buyers outside of Europe to question whether deepening their own relationships with Russia in the energy sector is viable. The Russians would be hurting themselves economically, at least for a time (oil is far more profitable, and the Russians are making huge windfalls by exporting it to China and India).

But when push comes to shove, nobody should be sitting comfortably. Putin may believe that when it comes to economic pain, Russia can outlast Europe, whose governments require the support of their people. That becomes increasingly difficult when homes are without heat and businesses are furloughing workers.

In a time of war, everything is fair game. If Washington and its allies in Europe are content to use control over the financial system to their advantage, nobody should be shocked if Russia exploits its clout in energy markets.