Given the worldwide climate of political intolerance, I often try to deflect hostility by prefacing my comments with the old saw that “reasonable people can disagree.” As a strong believer in intellectual freedom and Socratic dialogue, I do in fact feel duty-bound to listen to the other side, or sides, of an argument.

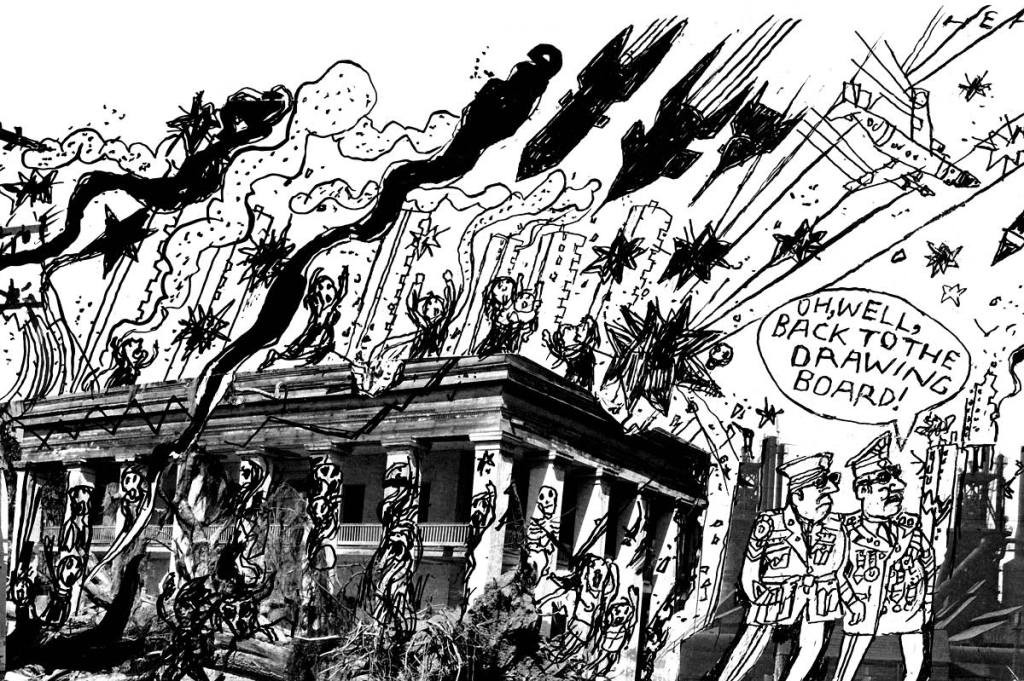

Yet there’s one subject about which I’m as close-minded as the wokest opponent of liberal debate — a topic about which I won’t brook any disagreement because there simply isn’t any reasonable form it can take: that is, George W. Bush’s and British prime minister Tony Blair’s disastrous decision to invade Iraq in 2003 and its deadly, still hugely malignant consequences in the Middle East. We should pause to consider the hundreds of thousands of dead, the millions of refugees and the vast waste of money that resulted. And we might also marvel that even the most enthusiastic proponents of overthrowing Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein have either recanted or pretty much gone mute.

This uniformity of opinion, whether or not it’s expressed out loud, is unprecedented in my experience. It’s easier, frankly, to find someone who will defend the Vietnam War, or non-intervention in World War Two, than to find any unrepentant partisans of the invasion of Iraq — because there aren’t any that I know of. Of course, it’s not so hard to understand why: even the most determined democratic reformer, human-rights hawk or warmongering imperialist understands that we made a bad situation much worse by eliminating a secular Sunni Muslim dictator to the advantage and empowerment of Iran’s aggressive Shiite theocracy, as well as other radical Islamic killers, including Hamas. I’ve found no more succinct summary of Anglo-American stupidity than the one written last year by Jean-Louis Tremblais in the center-right French newspaper Le Figaro. Above and beyond America’s and the UK’s contempt for the United Nations and international law, their lying on a grand scale about Saddam’s nuclear and chemical-weapons capability and their killing and maiming of so many innocent people, Tremblais wrote, “It’s not an exaggeration to say that the Islamic State [Daech] is the monstrous child of Uncle Sam and al-Qaeda. An uncontrolled and uncontrollable Frankenstein creature. By dismantling a state [Iraq] in which secularism was imposed, Washington reawakened and stirred up the religious question.”

Prominent pro-invasion liberals such as George Packer and Michael Ignatieff saw the light fairly early and astutely changed their positions. Packer’s renunciation of the invasion produced a bestselling book; Ignatieff’s led to a 2007 New York Times op-ed in which the future Liberal Party leader of Canada referred to the Iraq invasion as a “debacle” and offered the insight that “acquiring good judgment in politics starts with knowing when to admit your mistakes.”

But unlike America’s reviled and ridiculed former president George W. Bush (now a portrait painter) and his neoconservative super-hawk advisors Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz and Colin Powell, there are certain prominent liberal hawks who have somehow escaped condemnation for helping to promote the invasion. Perhaps the one who’s still most prominent is Samantha Power, Barack Obama’s last ambassador to the United Nations and America’s high priestess of humanitarian and human-rights-based military intervention. Power’s 2002 book, “A Problem from Hell,” established her as a major spokesperson for “moral” war, although principally to prevent the kind of “genocide” that allegedly occurred in places like Bosnia and Kosovo in the 1990s.

As the 2002-03 campaign for regime change in Baghdad intensified, Power, at the time a journalist and academic, seemed to become ambivalent, never explicitly endorsing Bush’s plan to go it alone with the UK. Nevertheless, she clearly wanted Saddam Hussein targeted by the world as a horrific human-rights violator and to be punished as such. This was the ploy that many liberals used to justify their awkward alliance with the neoconservatives driving the invasion policy. “We don’t approve of aggressive, unilateral American foreign policy,” went their argument, “but when it comes to gassing Kurds, murdering political opponents and threatening neighboring states with chemical or atomic weapons, there’s a good case for sending in the army.” I recall being shocked by an old journalist acquaintance, a left-wing anti-establishment critic of US foreign policy, when he told me privately at a pre-invasion colloquy sponsored by Harvard’s Carr Center for Human Rights Policy that Iraq was full of middle-class strivers thirsting for democratic government who couldn’t wait for their American and British liberators to arrive.

But Power was cagier, and more ambitious. In her 2019 memoir, The Education of an Idealist, published after eight years in the Obama administration, she writes: “While Saddam was a merciless dictator, I did not see that as sufficient reason to go to war… Although I abhorred the prospect of Saddam remaining in power, I ended up speaking out against the Iraq War on a number of occasions. As I told Newsweek in early March 2003, roughly two weeks before the war began, ‘[The invasion] will ratify and fuel the bubbling resentment against the US, and this anti-Americanism is the sea in which terrorists thrive.’” This quotation is not a statement of opposition to invading Iraq. It is a commentary on the potential consequences of an invasion. And most everything she said or wrote in the immediate run-up to the war was equivocal. It’s not good for the United States to invade without allies, but if it does, as she said on NBC’s Hardball on March 10 that year, “an American intervention likely will improve the lives of the Iraqis. Their lives could not get worse, I think it’s quite safe to say.” And “it would be great if human rights were a necessary condition” for the invasion. In other words, it’s OK if the invasion takes place with respectable partners on our side, preferably ones who believe in “human rights,” which is where she and Tony Blair come in.

During Power’s campaign of prevarication, I was busy opposing the invasion, wherever and whenever I got the chance. So I suppose it was inevitable that we would meet on a TV set, though this one was so obscure that it’s near impossible to find the video anywhere today. The scene was a studio overlooking Times Square on the evening of February 13, where BBC Four was premiering a new show called Manhattan, which aimed, according to its host, Stephen Evans, to help viewers in the UK understand “what they make of us and what we make of them.” In this first episode of a seven-part series, there were two American journalists, me and the very right-wing Ann Coulter, one British historian, Niall Ferguson, and the London-born Irish-American Power, though she hasn’t a trace of an accent and appeared to be a thoroughly assimilated American. God bless the BBC, since no US program would ever have assembled such a diverse group of clashing guests. The topic was the orange-terror alert then spooking New York City, which the good-humored Coulter welcomed as utterly justifiable, as well as the massive purchases of duct tape for use in reinforcing windows against bomb explosions. I said I felt like I was in the middle of a Tide detergent commercial, but my serious point was that the terror alert was part of a government advertising campaign designed to juice up war fever against Saddam, who just a week earlier had been falsely allied with al-Qaeda by the New Yorker’s Jeffrey Goldberg.

I sparred with Ferguson over Middle East and British colonial history, but once I’d changed the subject to impending war, that took center stage. And that’s when Power gave herself away by joining a throuple with Blair and Coulter. I didn’t so much mind Coulter’s strident pro-war stance, or her supposedly deep admiration for the prime minister. It seemed authentic, or at least an authentic role she was playing in the hope of appearing more often on Fox News. Power’s initial pose of dispassionate analysis was more troubling, though she suddenly and passionately let down her hair. “I actually agree with Ann that it’s a very, very principled stand on Blair’s part,” she said. “I don’t think it’s cynical… I think if I could say what we get from Blair… we get an individual who is trusted by the left in this country for a whole host of reasons… He has really helped legitimate the war domestically… He believes this is a righteous foreign policy, and it has to do with Saddam’s human-rights record. And he believes that… his country is a vulnerable country because of the threat that the terrorists pose, and this is a way of decapitating a monster, domestically and internationally.”

I still think I was right to call Blair “John Knox with a winning smile” or perhaps a “Christian fundamentalist” — to say he was “a little crazy,” suffering from “political hubris,” and craving “the glory that [he] expects to derive from being on the winning team.” And I’m still disgusted with Bush and Blair for bringing on this calamity that got my good friend’s son killed in Iraq. But I’m mainly disgusted with Samantha Power and her lot of careerist bet-hedgers — the lies she supported, all with the best of intentions, all in the name of doing good. A problem from Hell? More like a problem born in the US and the UK.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply