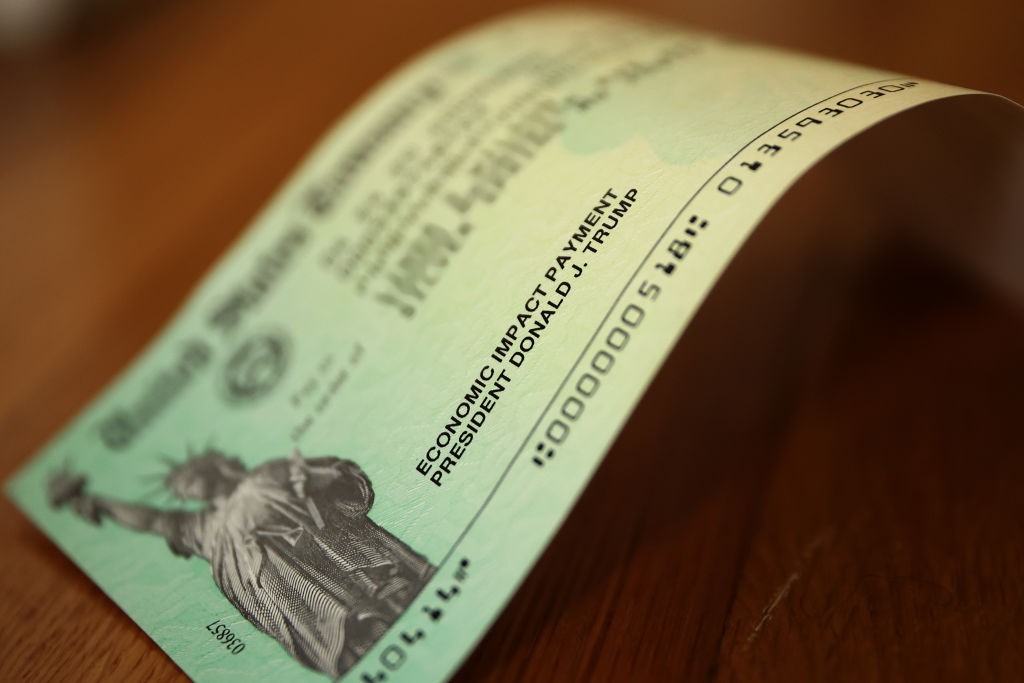

‘Money for Nothing’ is more than just the name of a Dire Straits hit from 35 years ago. Today it’s the guiding principle of an increasingly wide spectrum of American political thought. Andrew Yang built his campaign for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination on a call for a universal basic income — a $1,000 monthly payout from the federal government to every adult in the country. When Congress in March fumbled for something grand to do in response to the coronavirus crisis, a consensus quickly settled on sending out $1,200 checks to most Americans.

But free money isn’t just an emergency measure or a faddish idea from the left. Variations on the theme have been explored by various right-leaning schools of thought as well, with wage subsidies — payments for employers to pass on to their workers — being one approach contemplated by ‘reform conservatives’ in the years before the election of Donald Trump. Federal payouts for having and raising children are also popular in some conservative circles as the answer to falling birthrates.

Something is seriously wrong here. Even a few libertarians were swift to say that the coronavirus situation is one occasion when mailing out money to everyone from the federal government makes sense — although these same libertarians lamented the $2 trillion deepening of the national debt as a result of the stimulus bill. (In fairness, the personal payments are a fraction of that $2 trillion.)

With the economy in freefall as a result of measures taken to ‘flatten the curve’ of the pandemic, extraordinary actions had to be taken to stave off catastrophe for millions of workers. But $1,200 isn’t going to stretch very far for workers who have lost their jobs, or even for those still employed. Nor is a flat, nationwide payment going to go equally far in the different regions of the country. New York City, where the cost of living is high, has been hard hit, but because of the income cutoffs decided by Congress, middle-class people there who earn a little over $100,000 a year (and pay an exorbitant proportion of that in rent) will not receive a relief check at all.

The excuse for such a poorly targeted policy is that there just isn’t time to make distinctions about real need. Other items in the stimulus bill are need-based (and others, predictably, are sheer political pork). A mass payout has to do some good, right? It will goose consumer spending, if nothing else.

But the problem of New York rents points to a general problem with such indiscriminate payouts. A fatal flaw in Yang’s scheme, for example, was identified over a century ago by the economist Henry George and his followers. They recognized that landlords would respond to their tenants’ newfound prosperity by raising rents, and therefore the landlords, not the tenants, would be the real beneficiaries. Landlords are in an exceptionally strong position to take advantage of indiscriminate money dumps, but they are certainly not the only ones who can do so. The potential for price shocks and uneven inflation in sectors where providers have unusual leverage over consumers poses the risk that the ultimate beneficiaries of a cash infusion will be the least needy or deserving.

Even more targeted remedies, such as the expansion of unemployment benefits, can have perverse effects. When Republicans pointed out that generous emergency unemployment payments would have the effect of disincentivizing work, the stock response from pundits was that nobody would take a higher income in benefits over the short run at the expense of a steady job in the long run. What the fixtures of elite-educated opinion media did not consider is that for much of the working class, jobs are not ‘steady’ or reliably ‘long-term’. When the short term is all you can count on, a short-term unemployment payout that’s higher than a short-term income from employment is the logical choice to make.

Yet even if it’s the right choice for workers, it’s the wrong choice for small businesses, which need a labor force they can afford. No doubt the pundits’ answer to that one will be more immigration. But that leads to even more perverse outcomes, ones that we have seen all too clearly, whereby American workers are abandoned to addiction, suicide and despair, while cheap new workers are shipped in to prop up businesses — and the Democratic party and its allies in the media university identity-politics industry.

What is ultimately at stake in mass payouts by the federal government and poorly conceived targeted benefits alike is the basic constitution of the nation’s political economy. That some conservatives and libertarians concur with the left about the utility of centralized distribution of income is not a surprise because on the left and parts of the right alike there is a belief that the old organs of American political and economic life — regions and states, localized hard industry, tightly bound families, and ethnic and religious communities — are now obsolescent. Protecting those fixed-place intermediaries between the individual and universal power so that they can exercise responsibility within their own domains is foolish: only the widest solutions adopted by the most powerful institutions — Washington, DC, the financial system and a few great mega-corporations — can relieve the distress of weak and dependent citizens. The alternative mindset, which traditionally embraced local government, economic protectionism and the dispersal of economic and political power away from the center, aims to make each layer of society semi-independent, more reliant on the next closest level of economics or politics rather than on the most remote.

These two ways of looking at life are still in conflict over policies like direct payments to citizens. It is a conflict that reveals everything about how our country and its economy became so fragile in the first place.

This article is in The Spectator’s May 2020 US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.