It is only fitting that the low point of the American labor movement occurred in 2009, the Year of the Rat. The Great Recession may have started with Wall Street speculation in the housing market, but your average American had most likely never heard of Henry Lehman or his siblings until the day Dick Fuld drove the 150-year-old bank bearing their name into the ditch.

But General Motors, Chrysler? Cars, even more than Hollywood, jazz and the semi-automatic rifle, are the quintessential American business. How could those get driven into the ground? As soon as freshly evicted homeowners finished packing the remains of their subprime split-levels into the backseats of their battered Tahoes, they went looking for culprits. They settled on the United Auto Workers.

While Congress and the Obama administration hammered out a multibillion-dollar bailout package for Detroit, the American public was fed a steady stream of news stories about the UAW’s “jobs bank,” which paid members near full-time pay not to work. The measure was meant to discourage the outsourcing that had taken a heavy toll on American workers, but to newly unemployed taxpayers it looked an awful lot like lazy union members feeding off the carcass of a once proud industry. Just eleven months after Lehman Brothers collapsed, disapproval of labor unions jumped almost 50 percent, while support plummeted from 59 percent to 48. Right-to-work laws, which prohibit requiring union membership as a condition of employment, spread from the south to the labor strongholds of the Rust Belt.

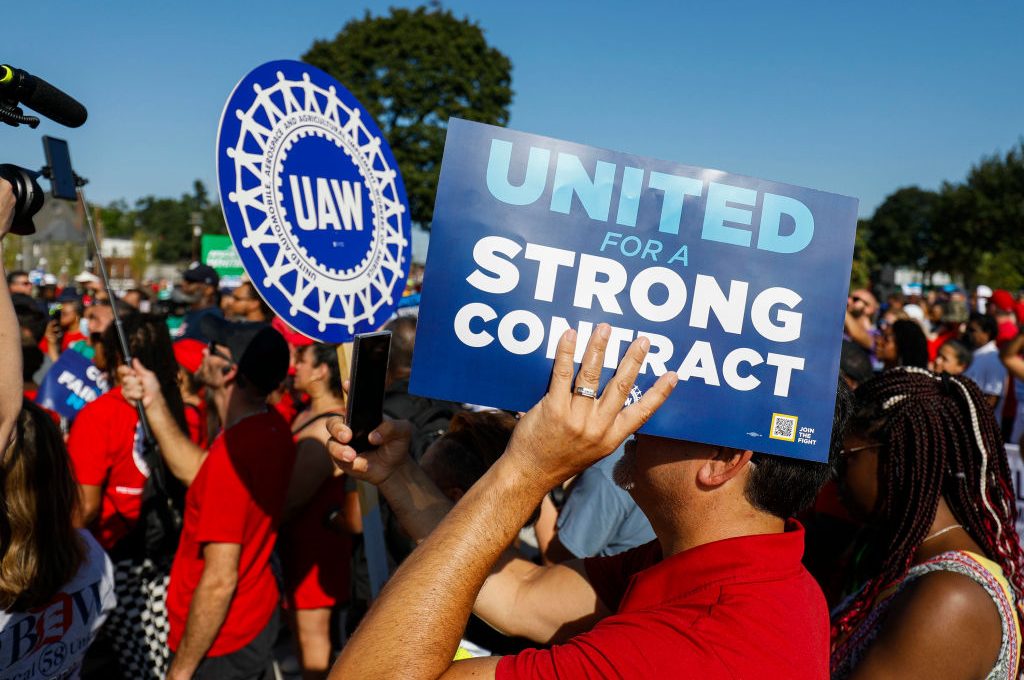

In the fourteen years since the Detroit bailout, scores of UAW executives, including two presidents, have been sentenced to prison time on federal embezzlement and corruption charges. Normally that sort of news would lead politicians to disavow their campaign donors, but politicians were tripping over themselves to get in on the most recent UAW strike. Joe Biden’s handlers escorted the president from the beach to Wayne County, Michigan, and made sure the press trumpeted that it was the first time a sitting president had ever joined a picket line.

What made the moment notable, however, was that no one from the White House had to clarify Biden’s comments — you got the sense that for once Biden knew where he was and why. More historic was the fact that Republicans wanted in on the action. Senator Josh Hawley and former president Donald Trump were out front trying to stand with the UAW even as union brass rejected their endorsements.

You can forgive Big Labor for its bewilderment at Republican support. The GOP has spent decades cracking away at unions, which in turn have spent billions cracking away at the GOP. This is 2023, the Year of the Rabbit, not the Rat, and it may go down as one of the more consequential moments in the history of organized labor.

Everyone from autoworkers to nurses, pilots and hotel concierges seems to be walking off the job these days. The public discovered how unlovable and unfunny celebrities are after writers staged a 148-day strike. UPS drivers won major concessions after threatening the same, while Starbucks baristas and Amazon warehouse workers are filing petitions to organize en masse. There is a common thread undergirding all of this: these are the workers hit hardest by the pandemic — either because of extended layoffs or, paradoxically, because they were deemed essential. The American public may have soured on unions during the Great Recession, but they are more supportive than ever following the pandemic, and unions’ favorability rating stands at thirty-eight points today.

Public perception plays a large role in any union’s decision to go on strike. In 2009, only 12,500 workers walked out on the job — more than 300,000 have done so in 2023. The difference between these two eras is not just material, but practical. The most high-profile strikes during the Obama and Trump eras were initiated by teachers’ unions from deep blue Los Angeles and Chicago and GOP-dominated West Virginia. Such walkouts would once have been unthinkable, particularly in an era in which both parents work. Despite the disruptions and the scramble for childcare, poll after poll taken amid these walkouts showed that citizens supported striking teachers — at least before parents discovered what those unionized teachers were forcing upon the student body.

The pandemic supplied the goodwill, and the teachers the proof of concept, but the urgency with which the labor movement has been waging these fights reflects a well-founded sense of desperation. Unions are facing an existential crisis caused by plummeting membership, which has remained in single digits for more than a decade, as well as a legal framework that threatens to erode that number further.

Over the past decade, the Supreme Court has been revisiting decades of liberal interpretations of the National Labor Relations Act which had increasingly granted considerable leeway to the labor movement as a necessary step to preserving labor peace. These legal efforts culminated in the 2018 Janus decision, in which the court held that mandatory union fees charged to government workers violated the First Amendment. Money talks, as the court concluded in Citizens United; and if money talks then any fee unions deduct from the paychecks of government workers amounts to compelled speech.

There is a real fear in the labor movement that the Roberts court will not stop at government workers and may soon extend the compelled speech prohibition to the private sector. Lower courts have already drawn such a conclusion. Southwest Airlines and its union found this out the hard way after a Christian stewardess was fired over her pro-life Christian views and criticism of union leadership. She won a multi-million-dollar retaliation suit and a federal judge ordered her reinstated and required the company to undergo religious liberty training.

The GOP may have helped secure First Amendment protections for corporations through Citizens United, but the same executives have been all too eager to spend their money imposing and enforcing a thoroughly progressive agenda in the private sector. The Southwest episode goes a long way in explaining why a sizable portion of the GOP, from Trump and Hawley to Senators Marco Rubio and J.D. Vance, who are willing to buck capitalism and laissez-faire economics out of opposition to the politicization of corporate boardrooms.

These politicians see organized labor as a cudgel that can beat back the worst graduate school impulses that have become fashionable in the C-suite and ESG-ratings organizations. The GOP has successfully deployed such attacks to gin up division between workers and their unions, which explains how 40 percent of union households vote Republican even if leadership remains fully in the tank for Democrats, pumping hundreds of millions of dollars into local, state, and federal politics each year.

The labor movement has received a pittance in return for its steep investment in the Democratic Party, particularly in the wake of Obama’s landslide second victory after the 2008 crash. Obama enjoys a reputation as a defender of the working man, and Democrats were quick to pay lip service in exchange for sizable union campaign donations. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer famously threatened the “nuclear option” for overriding Senate confirmation procedures to get Obama’s appointees onto the National Labor Relations Board, but these bureaucratic victories, while good for professional union activists, did not do much for the average worker. Wages remained stagnant. And while inequality and CEO pay ratio remained a popular talking point, Obama and crew achieved little to improve their lots.

Despite two years of united governance Democrats failed to pass what has now become the PRO Act, a quixotic legislative package that would strengthen labor leverage in negotiations and ease the path to unionization by doing away with secret ballot votes. The labor movement’s most visible accomplishments during the Obama years were indirect, helping Democrats to win elections. Organizations like the Service Employees International Union shelled out millions to front campaigns to increase the minimum wage to $15 an hour; and while these efforts had some success at the state level, they have failed at the national level. The federal minimum wage stubbornly remains $7.25 per hour. The broader minimum-wage fight provided marginal benefits for actual dues-paying members, particularly in the service sector where many collective bargaining agreements benchmark entry-level pay to the minimum wage.

While pay remained stagnant, the other upsides to union membership were directly targeted by regulations championed by the Obama administration, which allowed financiers to slash pension and retirement benefits for union workers in an effort to address hundreds of billions of dollars of shortfalls. But the greatest pain came from Obama’s signature and most consequential legislative achievement. Obamacare took direct aim at union healthcare benefits by attempting to impose a tax on so-called Cadillac plans, the blue-chip feather-in-the-cap of any union negotiation. Ironically it has been Republican opposition to Obamacare that spared union health plans. Now, with healthcare and retirement taken off the table, it has never been more urgent for unions to prove their worth, which is why they have stepped back from broader and explicitly political social changes like federal minimum wage policy and are instead fighting for direct salary increases and job security measures for their dues-paying members.

The failure of Obama to deliver for his blue-collar voter base is rightly seen as a main driver for Donald Trump’s shocking Rust Belt sweep in 2016, but Obama’s legacy is also seen in the flurry of activity and labor unrest in America today as unions fight for pay hikes to offset member anxiety over their uncertain health and retirement plans.

The labor movement is rightly confident in its ability to wage strikes free of repercussions, particularly at a time when its traditional opponents in the GOP have soured on corporate HR. This is a partnership, however, that could prove short-lived. The leaders of the union hierarchies themselves often fall prey to the same “woke” forces that control the much-vilified human resources departments in the corporate landscape. The Teamsters Union, for example, which represents dock workers and truck drivers, recently removed female pronouns from the maternity section of its contracts. Current UAW president Shawn Fain pulled off his election upset in a runoff against former president Ray Curry with support from graduate students. The institutional forces that captured corporate America are firmly entrenched in union leadership.

The labor movement may soon recover its lost leverage over both employers and politicians in both parties if it is able to generate material benefits to workers, but that will depend on its ability to resist the C-Suite excesses that alienate members, lawmakers and the public. Given the militancy of modern labor leaders like Shawn Fain and Randi Weingarten, that may seem impossible; but then, so was the idea that GM could ever go bankrupt.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2023 World edition.

Leave a Reply