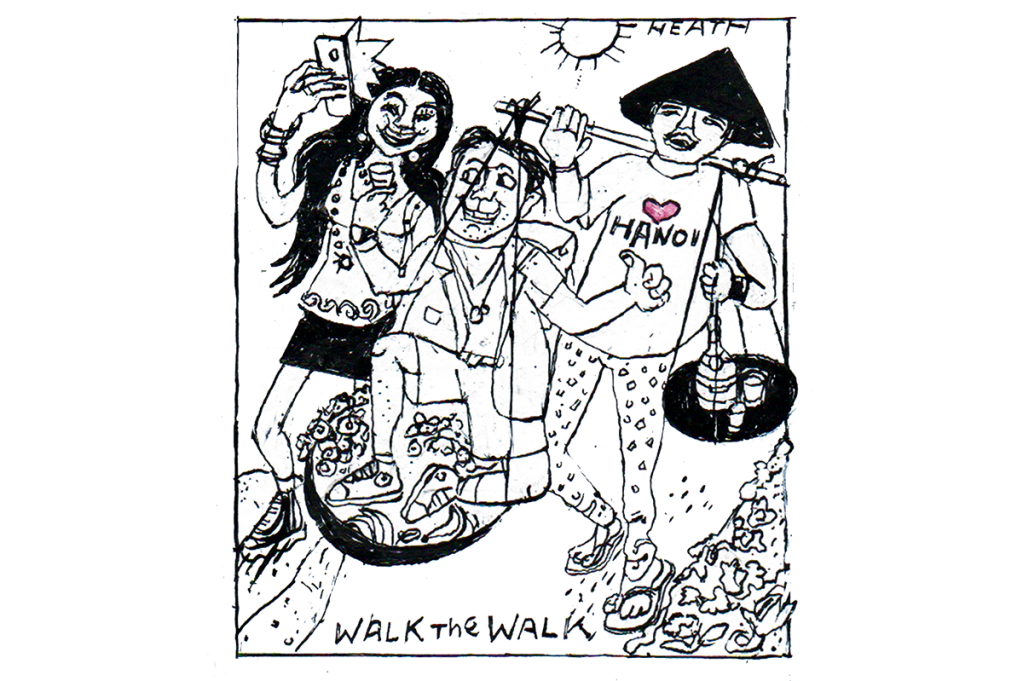

I let the roosters wake me at 4:30 a.m., since it’s already 88 degrees out, will be 100 by noon and I want to get in my full fifteen-mile walk without suffering heat stroke. My intended route is from my small rented apartment in southwest Hanoi, due east to the banks of the Red River, then back again, or maybe something else entirely. My plans are always rough, the daily walks changing depending on what I see, who I meet and what strikes me. That is why I walk, rather than drive or bike: so I can change stuff up on the fly — and let events, people and things I find along the way determine where I go. The only things that stay constant are aiming for between ten and twenty miles a day, and never using cabs. Buses now and then, to complete the circuit, or cross long empty stretches, but never cabs.

I’m in Hanoi for a month as part of my Walking the World project, in which I — you guessed it — walk around various cities and parts of the world. “Project” makes it sound formal. Really, it’s pretty ad hoc. Before Hanoi I was in Seoul; after Hanoi I will fly to Liverpool with the intention of walking across England to Sunderland. All that could change, depending on what strikes me and who I meet along the way.

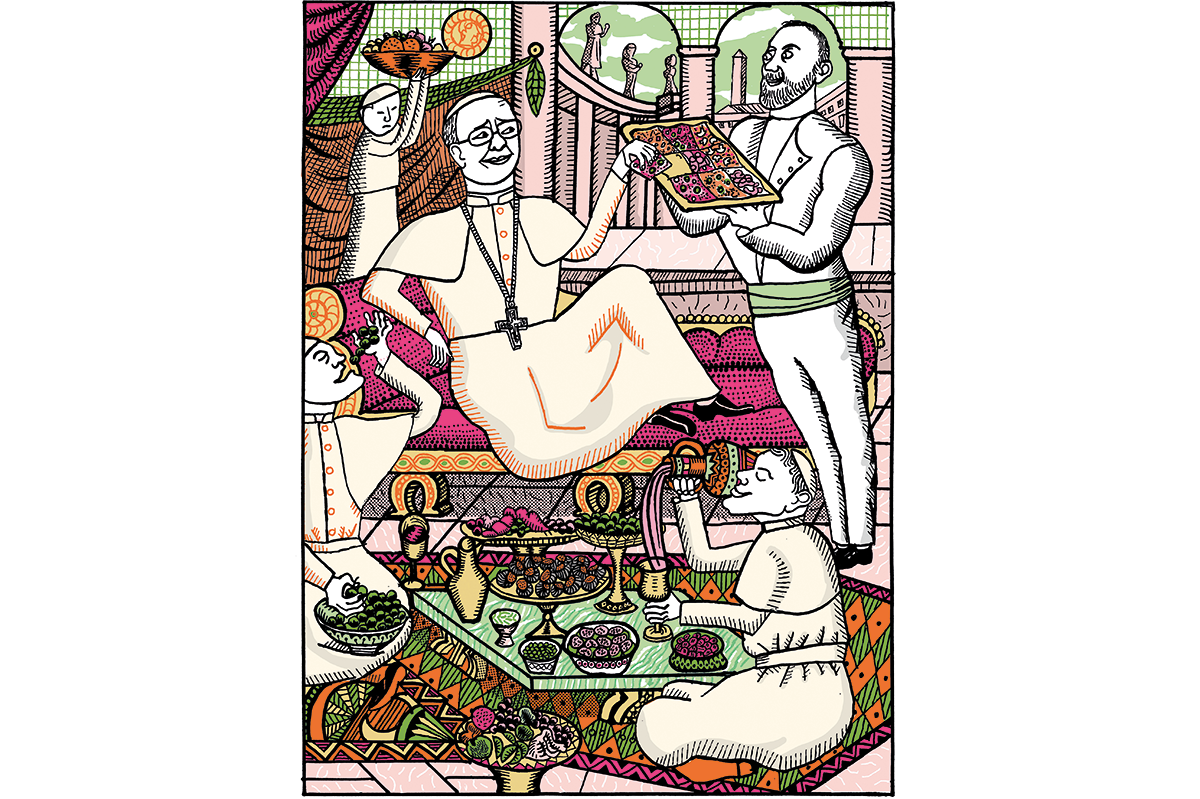

I spend the first fifteen minutes after getting up gulping water and stretching, both to ward off injury and to try and temper my hangover. My walk the day before was punctuated with stops where I was given free food, lots and lots of free alcohol and big hits of tobacco from massive bamboo bongs. The idea of turning any of them down, or, God forbid, trying to pay for any of it, was simply a no go. I was the guest, and I had to accept whatever was offered to me. And lots and lots was offered to me. That is the biggest obstacle so far to walking Hanoi, which is famous for its swarms of mopeds, cluttered sidewalks and general infrastructural nastiness: the continual offers of hospitality. It is the most generous and warm city I have ever been in. I cannot walk without being invited into homes, offered this and that and shown a genuine warmth that is jarring. I have so much and you have so little — and yet you are treating me. Along with prior walks in Lima, Kyiv, Bucharest and many other places, it has made me viscerally understand how spoiled, and yet miserable, we well-to-do Americans and western Europeans are.

This morning’s hangover didn’t come from the drinks along the walk, but from three hours of toasts last night only blocks from my apartment. After yesterday’s walk I’d swung by the home of a family that days earlier had treated me to food and drinks, after I stopped in front of their house to listen to music coming from the local community’s party headquarters across the alley. I thought I’d bring them gifts to thank them (bags of US cookies and a pack of beer), only to quickly realize I’d made a huge tactical mistake. Bringing gifts only meant they now had to outdo me. So, until midnight I again sat in the alley, listening to patriotic songs, as more and more neighbors swung by, bringing more and more food and drink, offering more and more handshakes, while everyone ignored my gifts, which sat untouched, mocking my inability to accept generosity for generosity’s sake, rather than as a game of one-upmanship. Now I had to suffer the consequences.

As with most of my social interactions in Hanoi, nobody in the group spoke English. But a lot can be navigated with the help of Google Translate, hand gestures and a little broken English. Still, it wasn’t until the last hour, when the seventeen-year-old son who spoke enough English to translate came out, that I got a better picture of my hosts. The father, a man of about my age, was self-made. From a small farming village in the north, he had built a business selling phone accessories from his living room and was successful enough to own the five-story home we were sitting in front of. It isn’t in the best part of Hanoi, mind you. No tourists come here. Ever. It’s in a part of town the guidebooks ignore, beyond maybe telling you to steer clear. But unlike the historic downtown, it’s what 98 percent of Hanoi is — and he should be rightfully proud. It’s a perfectly fine neighborhood as far as I’m concerned.

As we got progressively drunker, he asked me a bunch of questions through his son. Mostly about why I was walking everywhere. Nobody in Hanoi walks long distances. Couldn’t he get me a car to hire? Or a moped at least? I tried to explain to him why I walked, using simplified versions of my usual rants. That you can’t understand a place unless you walk it. That the best parts of a city are those unseen by tourists — and how I’ve learned so much over the years by engaging with people as, well, people, not statistics. Most of it was lost in translation, and he kept looking at me oddly, before I finally said, “I wouldn’t have met you, your family, and all your neighbors, if I didn’t walk.” That he got.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2022 World edition.