We are all improvising now. In front of the supermarket, at 6.30 a.m., we stood at a cautious distance from one another. Then the doors opened, and men and women rushed forward as one, in a habitual desire to be first inside the shop.Normalcy ended last Wednesday. My office closed its doors, like many others, with the optimistic hope of opening them again in two weeks. I had a beer with a friend in a quiet bar as my phone buzzed with news of closures and infections. I doubted there would be another pub night soon.It is a beautiful spring in Tarnowskie Góry, in the Upper Silesia region of Poland. Of course, few of us are in a position to enjoy it. All the bars, cafés and restaurants have been closed. No mass gatherings are allowed. No one could stop us from meeting our friends but most of us are not about to take that risk. I have been on a couple of early morning walks when no one is around but this might be unsustainable. After all, if everyone went for a walk it would turn into an accidental mass gathering.For many of us, social distancing has been a miserable annoyance. I will lose a lot of money, and a lot of good time in the sun, but it is not a home-threatening, food-threatening kind of loss. Others will suffer more. It would be petty to complain about the loss of restaurant dinners, beers and haircuts but it is not petty for chefs, waiters, barman, hairdressers and entrepreneurs to feel despair. Countless people are going to lose their livelihoods.You cannot have enough admiration, naturally, for the doctors and nurses on the front lines of this struggle. Those of us who have been fortunate enough to have been able to work from home, though, should not forget the men and women who sell us food, the truckers who carry it to us, the workers who take our trash, and countless other heroes laboring out of sight. They must be rewarded for a sacrifice that they have had no choice but to make.As I write, Poland has 246 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and five deaths. This is substantially lower than the numbers of confirmed cases in Italy, France, Germany and the UK, though with widespread testing it could be somewhat higher. Still, it looks as if preventive measures have at least succeeded in slowing the spread of coronavirus. The Polish government was quicker to close the borders than governments of other countries, and schools, universities and businesses soon shuttered up. Only churches, for better or worse, have stayed open, though for 50 people at a time — and many believers have decided to stay at home.Poland would struggle to cope with an outbreak on the scale of that faced by Italians. Poles have about half the critical case beds per 100,000 people, though the British, Swedes and Dutch have fewer, and Polish hospitals have had staffing shortages as doctors and nurses have been drawn to wealthier nations. Environmental and lifestyle factors could also make Poles dangerously vulnerable to coronavirus. Low air quality appears to weaken our resistance to it, and some Polish provinces, like Silesia where I live, have some of the worst air quality in Europe. (Twenty-nine of Europe’s most polluted cities, a recent report found, are Polish.) Smoking also seems to make us more vulnerable, and smoking is more common in Poland than other European nations. In addition, there is a theory that family transmission has been high in China and Italy because of multiple generations living together, and it is quite common in Poland for children, parents and grandparents to live together.All this makes the drastic response of the Polish government understandable, and the low initial rate of transmission welcome. Still, the economic impact of the closures should not be understated. Walking through my town, I cannot help but be dismayed by the quiet tragedies that lurk inside each empty restaurant, bar, shop and gym. One sweet new shop sold decorations for parties and events. I cannot imagine how devastating the impact of innumerable canceled parties, weddings and communions has been for the owners and employees.It is horrifyingly sad that as my town, like many others, has begun to reap the blessings of new businesses, investment and tourism, this global crisis has cut at their roots. Still, Poles are nothing if not resilient. Many businesses, including the one I work in, have done a remarkable job of transitioning to online services and sales. Thousands of people have calmly and stolidly accepted severe new constraints on their liberties. (Even black humor has prevailed. A popular theory holds that the virus can be killed with Polish vodka.) We know that most of us would survive coronavirus but we also know our older family members, friends and neighbors, who survived communism and in some cases Nazism, should not be endangered by our own selfish desires, and that the immunocompromised among us should be protected.Sometimes people from every nation have an excess of history in their discourse. In more normal times, history can be a source not only of wisdom but of misguided hubris or resentment. It depends on how it is dealt with. Now, though, in Poland, I think history can provide a source of inspiration. People know their parents and grandparents have dealt with curfews and shortages before, and not, unlike in this gloomy period, in a worthy cause. People know, as well, that Poland has been through far worse before rebuilding its society. A poxy virus cannot equal the debilitating consequences of partitioning, Hitler and the Soviets, and Poles rebuilt their homes before and will rebuild them again. All we need are patience and watchfulness, and the hope that in the summer the young and old will mingle in the parks, and pubs, and restaurants once more.

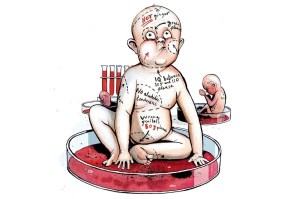

Waiting for corona in Poland

A poxy virus cannot equal the debilitating consequences of partitioning, Hitler and the Soviets

A Polish health official checks temperatures of people arriving on foot or by car crossing the Polish-German border

We are all improvising now. In front of the supermarket, at 6.30 a.m., we stood at a cautious distance from one another. Then the doors opened, and men and women rushed forward as one, in a habitual desire to be first inside the shop.Normalcy ended last Wednesday. My office closed its doors, like many others, with the optimistic hope of opening them again in two weeks. I had a beer with a friend in a quiet bar as my phone buzzed with news of closures and infections. I doubted there would be another pub night…

Comments

Share

Text

Text Size

Small

Medium

Large

Line Spacing

Small

Normal

Large