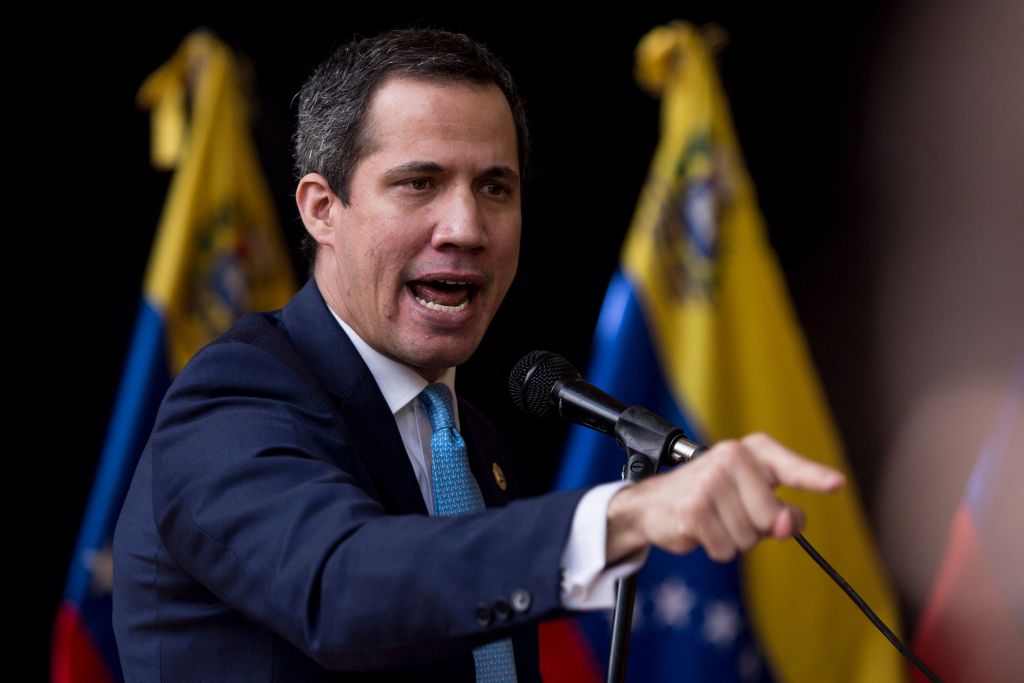

2019 was a banner year for Juan Guaidó, a relatively obscure Venezuelan lawmaker who announced to a crowd of thousands in the heart of Caracas that he, and he alone, was Venezuela’s new interim president. The United States and dozens of other countries in Europe and Latin America quickly followed up with official recognition for the fresh-faced head of the Venezuelan National Assembly. Nicolás Maduro, the man who took over the presidency after Hugo Chávez’s death, was for all intents and purposes relegated to the status of an isolated despot who had no legitimate claim to the Miraflores palace.

2022, however, has brought Guaidó and his international supporters back down to earth, with the opposition ditching his government in a 72-28 vote. Venezuela’s anti-Maduro coalition is notoriously fractious, but they are apparently unified enough to make a change at the top.

Much has changed since Guaidó became the public face of the Venezuelan democracy movement. At that time, Maduro was often depicted as a spent force. He was a virtual pariah in Latin America, had dismal approval ratings and constantly had to wonder whether his poor performance would eventually lead key members of the military to switch sides or take matters into their own hands.

Venezuela’s economy was undergoing the worst economic contraction in peacetime of any nation in modern history. Combined with Maduro’s colossal economic mismanagement and US sanctions on Venezuela’s oil industry, a country that was once the wealthiest in South America had fallen to bottom-feeder status. Between 2013 and 2021, the economy shrank by 75 percent, and buying power declined even more. Ordinary people were scavenging for food in garbage cans. Oil production plummeted from an average of 6.3 million barrels per day in 2013 to 1.2 million barrels per day in 2020. The lack of opportunity and exponential poverty forced millions of Venezuelans to leave for Colombia and other countries in the region.

Yet despite all of the pain and suffering, Maduro will enter 2023 in perhaps his strongest position since first ascending to the presidency nearly a decade ago. Guaidó’s 2019 coup attempt proved to be a godsend for Maduro, who used it as an opportunity to locate those in his administration who were actively planning against him. Maduro’s hold on the Venezuelan security forces is solid, with the top brass viewing him as the only game in town. There is no major opposition movement inside Venezuela to speak of — and even if there was, the Venezuelan people are so fed up with politics in general that it’s questionable such a movement would inspire much confidence.

Guaidó continues to press the case for democracy, dignity and transparency, but in reality he’s little more than a figurehead. Maduro has control over all the state institutions; Guaidó doesn’t control much of anything (when it comes down to it, the Venezuelan government assets frozen in US banks can be released at Washington’s discretion). Maduro controls the army; Guaidó had trouble cobbling together even a few hundred rank-and-file troops to join him in a revolt. Maduro has partners such as Russia, China and Iran that are willing to bail him out; Guaidó’s partners have long since tired of him. Washington saw Guaidó less as presidential material than as a way to build a case for deposing Maduro, yet Maduro has proven far more talented at cutthroat politicking than his enemies gave him credit for. As former New York Times Andes bureau chief William Neuman wrote back in November, “the fact is that Mr. Maduro is president of Venezuela and Mr. Guaidó is not.”

The United States is thus changing its strategy. While Washington’s overall policy remains regime change in Caracas, the Biden administration is balancing sticks with carrots. During the Donald Trump era, negotiations with the Maduro government were seen as unseeingly and morally repugnant — the objective was to use economic pressure to push the dictator out of office. The current White House, however, is publicly supportive of intra-Venezuelan talks and is indeed facilitating them. After Maduro and the opposition signed a humanitarian accord in late November, unlocking $3 billion in overseas assets to help address the country’s socioeconomic ills, the US Treasury Department permitted Chevron to resume small extraction operations in Venezuela.

Further US sanctions relief will be contingent on progress in the talks currently taking place in Mexico City. Ideally, the United States envisions an agreement that lifts the restrictions on Venezuela’s opposition political parties, frees political prisoners, and schedules a new round of presidential elections to be overseen by impartial monitors. Realistically, Maduro will be a candidate in any presidential contest, if only because otherwise he doesn’t have much of an incentive to cooperate with the process. Whether we get that far along is unknowable at this stage.

But the mere fact that Maduro, a huge source of Venezuela’s problems, will need to be a part of the solution is likely causing considerable headaches for Juan Guaidó and his political allies — those who are left, anyway.