Jose Antonio Ibarra, a twenty-six-year-old Venezuelan illegal immigrant, was charged in connection with the gruesome murder of Laken Riley, a nursing student at the University of Georgia last week. Another Venezuelan, thirty-two-year-old Renzo Mendoza, was arrested last week on two felony charges for sexually assaulting an underage child in Virginia.

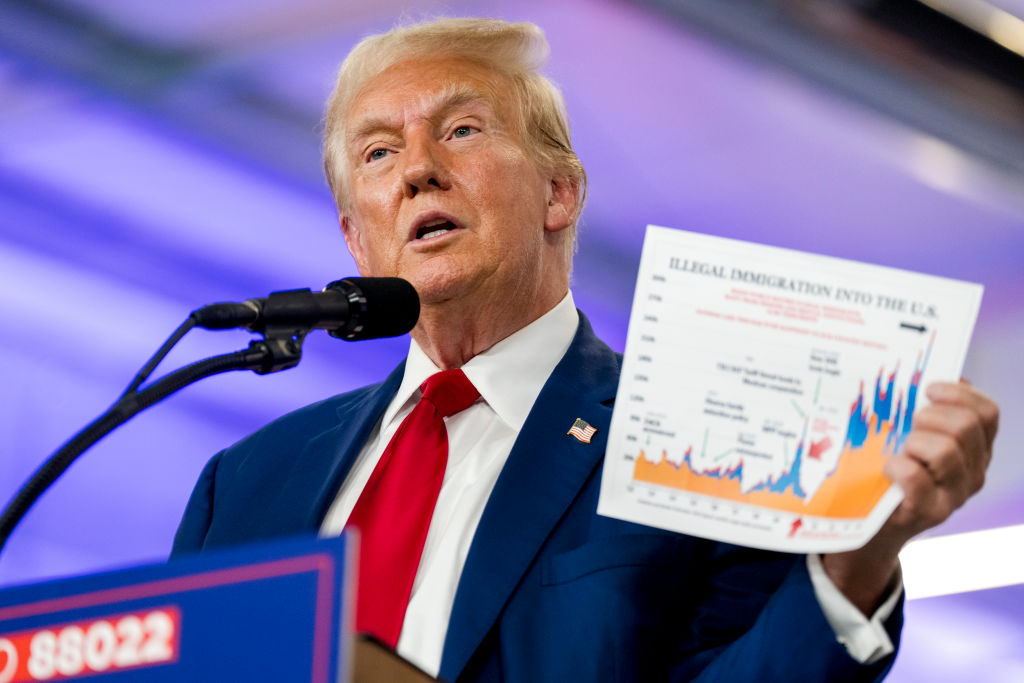

These cases, along with a series of others connected to Venezuelan migrants, have become central to the debate on immigration policy. Tuesday morning, for instance, Republican members of the House Judiciary Committee sent a letter to the Department of Homeland Security asking for more information about Ibarra.

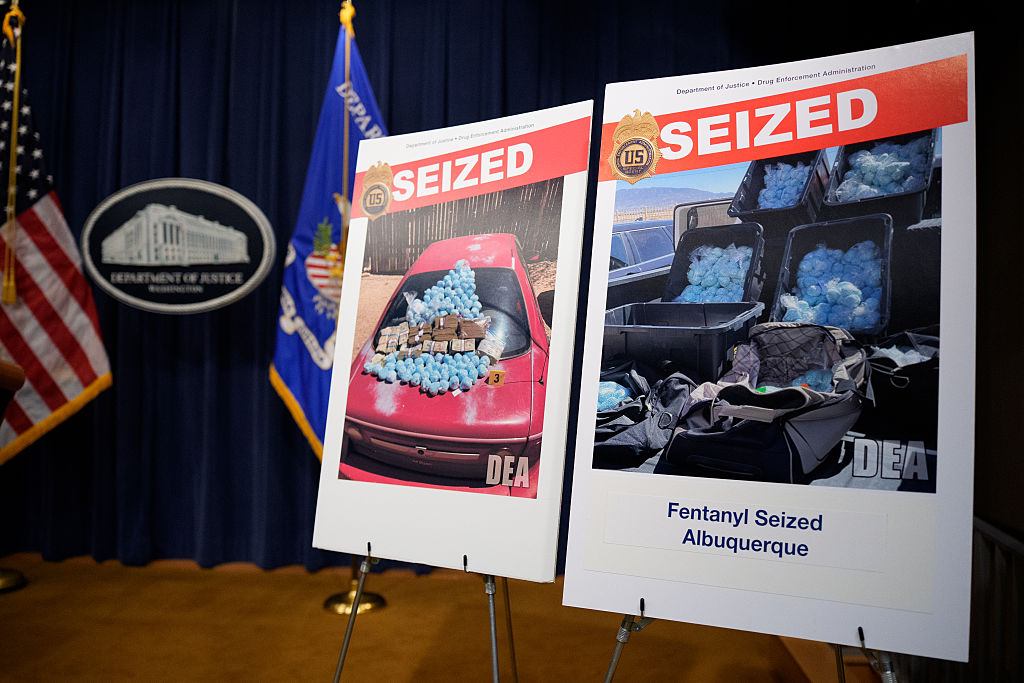

At the same time, the New York Police Department is cracking down on a Venezuelan gang, the notorious Tren de Aragua, that is connected to more than sixty robberies in four of the city’s five boroughs.

Tren de Aragua, the largest criminal organization in Venezuela, is well known among its citizens for having controlled one of the country’s most infamous prisons: the Tocorón prison in the state of Aragua. Much has been said about the practice of emptying prisons and about certain countries “not sending their best.”

And Tren de Aragua has been causing trouble in countries ranging from Colombia to Chile. The name of the gang, which translates to the Aragua Train, originated from an unfinished railway project. Under the leadership of Héctor Rustherford Guerrero Flores, alias “Niño Guerrero,” the gang expanded to a criminal organization that goes well beyond the Venezuelan state. Their criminal activity in Lima, the capital of Peru, has inspired animosity between locals and migrants.

Now, it has more than 2,700 members and the NYPD confirmed its established presence in the United States.

Due to the Maduro government’s unofficial policy of handing control of prisons to pranes (crime bosses), Tren de Aragua found ways to grow that other countries’ gangs could only dream of. By expanding their criminal networks, they even made the prison into their own palace à la Pablo Escobar — including its own nightclub, zoo, pool and restaurant.

It is difficult to pinpoint how many migrants have connections to the gang, but the experiences of Latin American states and the ongoing criminal investigations offer more than enough reasons to worry. Additionally, it has been reported that Venezuela had the lowest violent death rate in the last twenty-two years in 2023, so the idea that many of its criminals have left to new horizons rings true.

With a porous border, a Maduro regime that openly weaponizes migration and big cities that are soft on crime, things could get worse before they get better.

Leave a Reply