Venezuela’s dictator Nicolás Maduro has been embarrassed. In a transparent bid to rally political support, he asked voters to demand that their government annex two-thirds of Guyana through a hastily called plebiscite.

Venezuelans did overwhelmingly support the plainly one-sided poll, but turnout was small and noticeably lacking in enthusiasm. It was not the result the regime expected or craved as it attempted to divert attention from political and economic woes in the face of a newly competitive presidential campaign.

In its decade in power, the Maduro regime has presided over economic collapse, including the largest humanitarian crisis in the modern history of Latin America. More than seven million people have fled Venezuela out of an original population of some thirty million, according to estimates.

The economy is a fraction of its size in 2013. Inflation tops Syria and Zimbabwe as the highest in the world. The regime and its supporters like to blame US sanctions for economic collapse, but the crisis began well before sectoral energy restrictions were levied in 2019.

This followed the hollowing out of the professional class years earlier, particularly those in the vital energy sector, as well as a fall in broader economic activity from the regime’s confiscatory approach to private enterprise and property. Massive corruption has long crowded out new investment. Deteriorating personal security has increased business costs; the once-vibrant tourism sector has collapsed.

The regime has nonetheless proven it can weather economic difficulties so long as it continues to generate sufficient income for regime officials, its security forces, provides state-sponsored benefits to core supporters and pays its debts to international friends including China. In the meantime, going back to its founding by Hugo Chávez, it has remained expert in coopting the democratic process to keep the opposition divided and claim repeated mandates to rule.

That potentially changed on October 22, when, against all odds and predictions, the opposition successfully held a primary election that nominated Maria Corina Machado to contest elections anticipated in 2024. Despite numerous regime-created obstacles, turnout exceeded expectations and the result in favor of Machado — over 90 percent — was overwhelming. Now facing a political threat it did not anticipate, the regime has attempted to undermine the result by claiming Machado is ineligible and must be authorized to run by the regime-dominated courts.

Which is where the border dispute with Guyana comes in. Because really, there’s nothing like threatening war with a neighbor to amp up nationalism and acclamation for a weakened government in the face of a strong domestic political challenge.

The border issues are not new. They are just newly prominent in the hothouse of Venezuelan politics. Since 1899, when an international tribunal ratified Guyana’s sovereignty over the Essequibo region, Venezuela has maintained its claim over the “stolen” province.

Chávez himself famously sought to keep the issue in lights by adding an eighth star representing Esequibo to the Venezuelan flag. Ultimately, however, he had larger issues and enemies with which to concern himself, including the United States and his western neighbor Colombia. And he died before the discovery of massive offshore oil deposits in Guyanese waters beginning in 2015 that raised the stakes.

Maduro, on the other hand, is more repressive, less popular and now faces a serious political opponent. Although most observers conclude he will never allow free and fair elections that could turf him from office, his own ability to maintain internal control would be enhanced by continued shows of public support that undermine viable rivals.

Taking a page from Chavez’s book, Maduro called a plebiscite on Esequibo, reasoning it would be a broadly popular initiative to get his supporters back onto the streets while raising the regime’s flagging popularity and forcing the opposition to line up in support, shifting the narrative and blunting Machado’s momentum. He also sought to inoculate himself politically from international oversight of the border dispute and allegations of democratic and human rights abuses domestically.

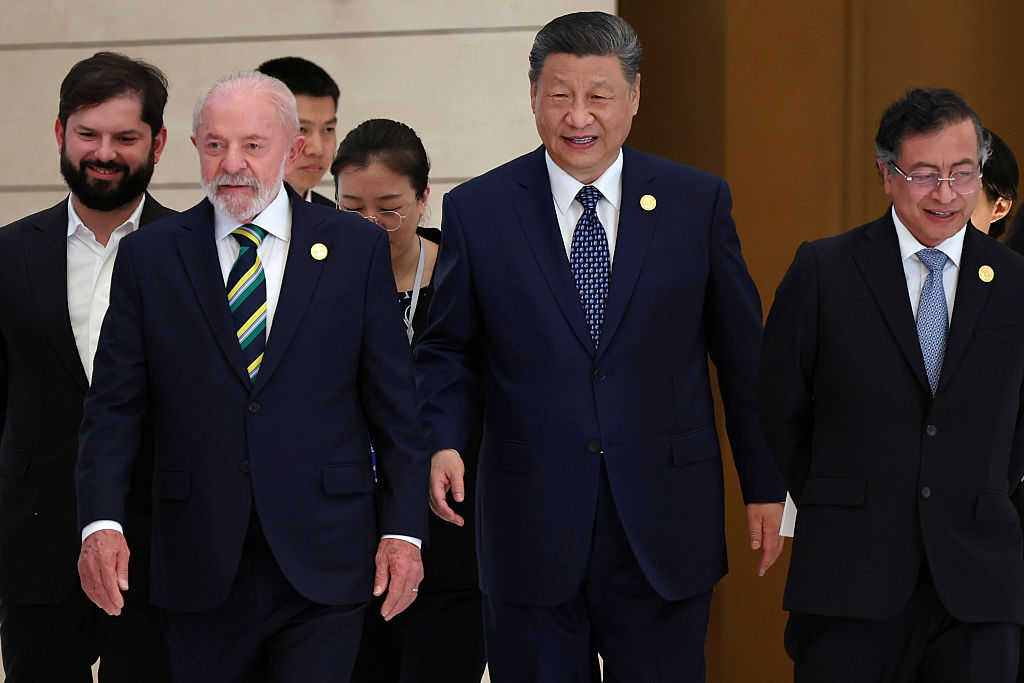

But voters had other ideas and the plebiscite fell flat. The international community including Brazil and the United States have urged restraint while Caribbean nations, some allied with both Venezuela and Guyana, are caught in between. Caracas’s erstwhile friends including Cuba, Iran, Russia and China have largely remained quiet.

Maduro faces a choice. He can seek to inflame the issue further or he can find another issue to flog. Further steps would probably involve an active physical presence in the disputed region, perhaps by agitators, squatters or regime-aligned paramilitaries seeking to provoke a Guyanese reaction that ratchets up calls for a Venezuelan response for “protection.”

Overt military action in the forbidding terrain, however, would quickly expose the incompetence of the once-proud Venezuelan military which has been gutted by years of corruption and internal politics. It would also potentially create a casus belli for the international community to act against Venezuela directly, something the regime has long been careful to avoid.

The fundamental issue is political survival, not conquest. Neither Maduro nor his Cuban advisors are stupid. His target audience is domestic, and he will probably aim to keep border issues frothy enough to bolster public support while claiming that the regime is the true protector of the Venezuelan nation, whereas the opposition only wants to parcel it off to foreign governments and investors. It’s a ridiculous contention, but it’s also a model that has worked well for Bolivarian leaders for almost twenty-five years.

And in a constrained media environment that lacks even the pretense of press freedom, the charges can land effectively: first the United States, then Colombia, now Guyana. Tomorrow it will be something else.

In the meantime, the regime will continue to take all possible actions to tilt events in its favor. The key for the international community is to maintain a focus on free and fair elections in 2024, including Machado’s full and timely participation, despite Maduro’s provocations. That’s the real issue worth fighting for.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply