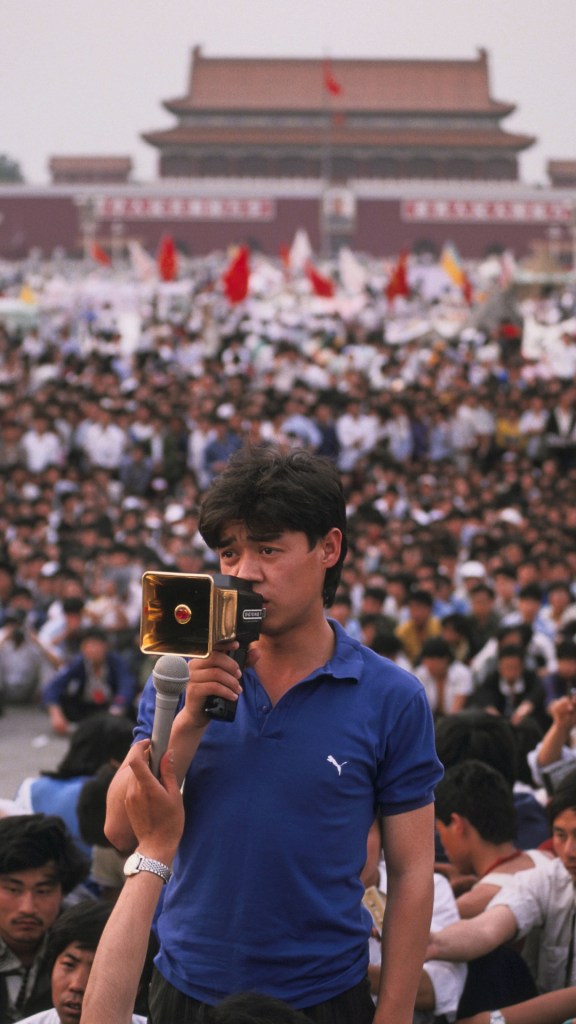

Anyone in China who remembers the Tiananmen Square protests will remember Wu’er Kaixi. As thousands of students began a hunger strike in May 1989, premier Li Peng held live, televised talks with the protest leaders. Wu’er Kaixi, then twenty-one, turned up to the talks in hospital pajamas, oxygen bag in tow, and berated the elderly communist leaders. It was an electrifying moment. After the CCP’s bloody crackdown, he found himself second on the party’s most-wanted list. He fled China and eventually ended up in Taiwan.

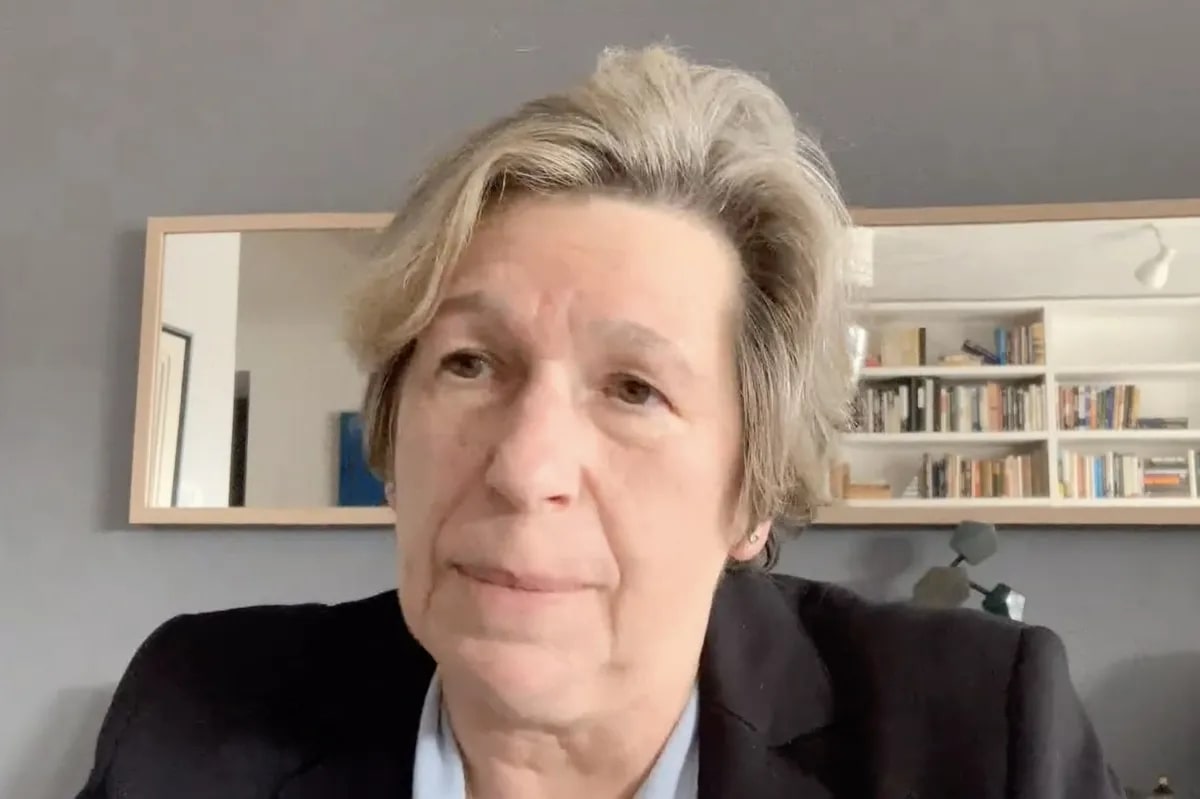

We meet in a Taipei jazz bar, which he tells me is his ex-girlfriend’s favorite spot. Kaixi, as he asks me to call him, talks about his survivor’s guilt. “I was a leader of a movement where many of the students were killed,” he says. “I’m the captain who didn’t die with the sinking ship.” The fifty-five-year-old has spent most of his life in exile. He has never stopped campaigning against the CCP, these days frequenting Taiwanese TV as a pundit and running the Taiwan Parliamentary Human Rights Commission, a hawkish caucus that scrutinizes human rights abuses within China. There are still flashes of the idealistic twenty-one-year-old who dared interrupt one of China’s most powerful men. He bashes the Taiwanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs for being too passive, criticizes the US for historically acting like “bouncers” and “cheerleaders” for China, and dubs Henry Kissinger “the most favorite guest of China” (not a compliment).

Yet he’s desperate to go back to China and face the authorities, even if it leads to imprisonment. He has tried — and failed — four times; every time the Chinese government has refused to let him back in.

‘All of these young Hong Kongers will have to find out in the most difficult way that they are powerless’

Overseas dissidents are “too weak,” he tells me. “We cannot access the real battlefield. In the first few years of our exile, I was hoping we would form the democracy organizations that can actually make a change in China. When it came to 2009, the twentieth anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre… [my] despair peaked.”

At the time, Beijing had just hosted the Olympics (“the whole world praised China”) but continued to lock up democracy campaigners. The CCP arrested Liu Xiaobo, who would later win the Nobel Peace Prize. The pair had campaigned together during Tiananmen. “The Chinese Communist Party was getting away with what they did twenty years ago. And then my teacher [Liu], my best friend, my mentor, is jailed for continuing what we did. Meanwhile, [dissidents like myself] are not doing anything outside of China. That’s when I decided to turn myself in.”

“I thought I could probably do a little more by being arrested,” he says. “If my action[s] and then also the consequences resulting from imprisonment can do just that little more to remind the world of unfinished business, I think I would have done much more than in the twenty years that I have been in exile, in that action alone. I will get my dialogue even in the form of persecution. I will turn that courtroom into my platform of dialogue. That’s the one thing the Chinese Communist Party wants the least.”

There is also a strong personal reason why he wants to return: Kaixi has not seen his parents since 1989. They are now in their eighties and have never met Kaixi’s two sons. “My parents are not getting any younger or healthier,” he says. “I’m afraid more and more that I will never be able to see them [again].” They used to stay in touch via Skype, but Kaixi’s family are Uighurs, and have suffered from Beijing’s increasing control of the Xinjiang region, which includes limiting contact with the outside world. Kaixi’s parents can only use WeChat (the Chinese messaging super-app), but the platform will not allow him to register an account.

I ask if it’s true that he has offered his silence in return for being allowed home. “It is. I want to see my parents,” he says. “I’ll take any deal for that.” But what about his “ultimate goal” of democratizing China? “It will be a dilemma,” he says. “But if there’s a deal on the table, I just don’t think I have the right to refuse my parents’ right to see me.” He doesn’t regret the students’ actions, but when I ask if he would do it again, knowing the price could be either death or exile, he says: “The answer is most definitely not.”

But there is no deal on the table. Beijing refuses to let him return. It is a more effective and painful punishment to leave him languishing abroad. In 2009, he flew to Macau, a special administrative region of China not considered part of the mainland, but the Chinese authorities deported him to Taiwan as soon as he tried to turn himself in at the airport. The following year he tried to enter the Chinese embassy in Tokyo, only to be arrested and detained by Japanese police. In 2012, he tried the Chinese embassy in Washington, finding its doors locked and phones unanswered. The fourth — and final attempt — was in 2013 when he tried to hand himself in in Hong Kong. He was deported again. Would he try again, then? “Maybe. You will know when it happens.”

After Hong Kong passed its National Security Law in 2020, a new generation of young pro-democracy activists were forced to flee. Does Kaixi have any advice for them? He’s reluctant to answer but reflects that his younger self should have thought more and talked less. He never expected, he said, to end up in exile — or to find out just how little can be achieved from exile. “It took me a long time to understand many of the things I have said to you,” he says. “All of these young Hong Kongers will have to find out in the most difficult way that they are powerless. Before they realize that, the world will demand them to be powerful.”

“That’s the other thing — everybody who is concerned about Hong Kong will have expectations from the activists. And those expectations become demands, which will ultimately become disappointment.” At a very high personal cost to themselves? “Yes. So how can I tell them that?”

Wu’er Kaixi looks tired. Most of his adult life has been spent in the shadow of decisions he made in a few tumultuous weeks when he was twenty-one, decisions he is not sure he would make again.

He has studied at Harvard and lived in France and the US; he has been a talk-show host in Taiwan and made two failed runs for parliament. He is divorced, single, and at one point suggests we meet again for another drink. He says he will continue fighting and finding “new front lines,” whether highlighting the plight of the Uighurs or promoting Taiwan’s international status to “blow away the Chinese Communist Party’s lie that Chinese people are not suitable for democracy.”

Ultimately, he says, he is still optimistic that China will make its way towards democracy. “I’m a Uighur, but I was born and raised in Beijing. I was among the hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people who took to the streets in the Tiananmen protests.” And while the movement was crushed then, he thinks it will prevail. “I have faith in the Chinese people.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator‘s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.