The decision is all anybody can talk about. Well, that’s not exactly true. It’s the banner headline in the New York Times, but if you scroll down or turn the pages, you will find something on “Smoke From Canada Fires Stretches From Midwest to East Coast,” and ‘Dangerous High Temperatures Stretch Across the South.” The world hasn’t stopped spinning and Mr. Putin is still causing trouble. A French police officer killed a seventeen-year-old French citizen of Algerian and Moroccan descent, touching off riots in several cities.

But the story that has riveted the attention of America is the Supreme Court’s decision in Students For Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College. And for good reason. Justice Roberts joined by five other members of the Supreme Court ruled that Harvard and the University of North Carolina have been engaged in illegal racial discrimination in the way these institutions selected students for admission. That finding, however, effectively ends the forty-five-year long game in which the Supreme Court has winked at colleges and universities that use racial preferences that were outlawed in 1868 by the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution.

The Fourteenth Amendment says, “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Known as the “Equal Protection Clause,” this sentence has always been understood as barring racial preferences — but for decades on end the Supreme Court has invented excuses not to apply this principle to college admissions.

It was tricky business. It started with the 1978 case of a white student named Alan Bakke who had been denied admission to the new medical school at the University of California Davis. Bakke sued, saying that he had been passed over in favor of other less qualified minority students. The Supreme Court eventually agreed that the university had illegally discriminated against Bakke on the basis of race. He was admitted and went on to a successful career as an anesthesiologist. But the Court that handed Bakke his victory was badly divided. Two of the justices wanted to base the decision on the Equal Protection Clause. Two others wanted to base it on Civil Rights Act. Four of the justices favored the University of California’s position, which had argued that racial preferences were a legitimate way to make up for the long history of racial discrimination.

That left one justice — Louis Powell — as the decisive vote. He joined the four conservatives but went on to write a meandering opinion in which he said that he would have voted for the other side if only they had based their case for racial preferences not on a claim that such preferences were needed to overcoming past injustice, but because racial preferences are a great way to enhance intellectual “diversity” in the classroom.

No other justice in the case sided with Powell on this. This part of his opinion fell into the category of “Supreme Court dicta” — things said by a justice that have no force of law.

But Powell’s novel idea of “diversity” didn’t die in its crib. What happened next is a long story. I know because I spent a couple of years writing that story in Diversity: The Invention of a Concept, which was published just a few months before the Supreme Court’s 2003 decision in Grutter v. Bollinger. That case stands out because Justice Sandra Day O’Connor used it to give official warrant to Powell’s concept of “diversity” as the patented way around the Equal Protection Clause.

O’Connor writing for the majority, decided that the University of Michigan Law School could use racial preferences in admissions if it justified them as the pursuit of “diversity” and it sufficiently obfuscated what it was doing by pretending that it was engaged in “wholistic assessment” of candidates. The university took what were plainly racial quotas but put them under a blanket in which “race” was said to be but one factor among many, and never a decisive criterion.

Post-Bakke litigation didn’t begin or end with Grutter, but the Grutter decision was the floodgate. It was taken by almost all colleges and universities as license to proceed with complete confidence that they could use pro-minority racial preferences with abandon, provided only that, if challenged, they could recite the appropriate mumbo jumbo about “wholistic assessment” and especially “diversity.”

By the time the US Supreme Court agreed to hear the Harvard and UNC cases, “diversity” had long since escaped its original context to justify unjustifiable practices in college admissions. The concept of diversity was applied to every aspect of education, including the curriculum. It jumped in the late 1980s into corporate America. It also grew into the “diversity consulting” business. It was swallowed wholesale by the arts, churches, sports and even greeting card companies. “Diversity” became a watchword for cultural sensitivity in all contexts, though it always had something of a double life. To a mainly white audience, it offered absolution in the form of overcoming racial division. “Diversity is our strength,” et cetera. But to a mainly black audience, it meant gaining access to formerly segregated spaces while being able to maintain a separate identity. This conflict in expectations played out in campus after campus. My colleague Dion Pierre and I wrote a close account of it at the ground zero of racially preferential admissions, in our book, Neo-Segregation at Yale.

Eventually both the word and the concept began to wear out. When something becomes too common to confer distinction, it is time for an upgrade. Hence “diversity” became “diversity, equity and inclusion” (DEI) and the rhetoric of integration and judging people by the “content of their character” was retired completely, replaced by “anti-racism” and inexpungable white guilt.

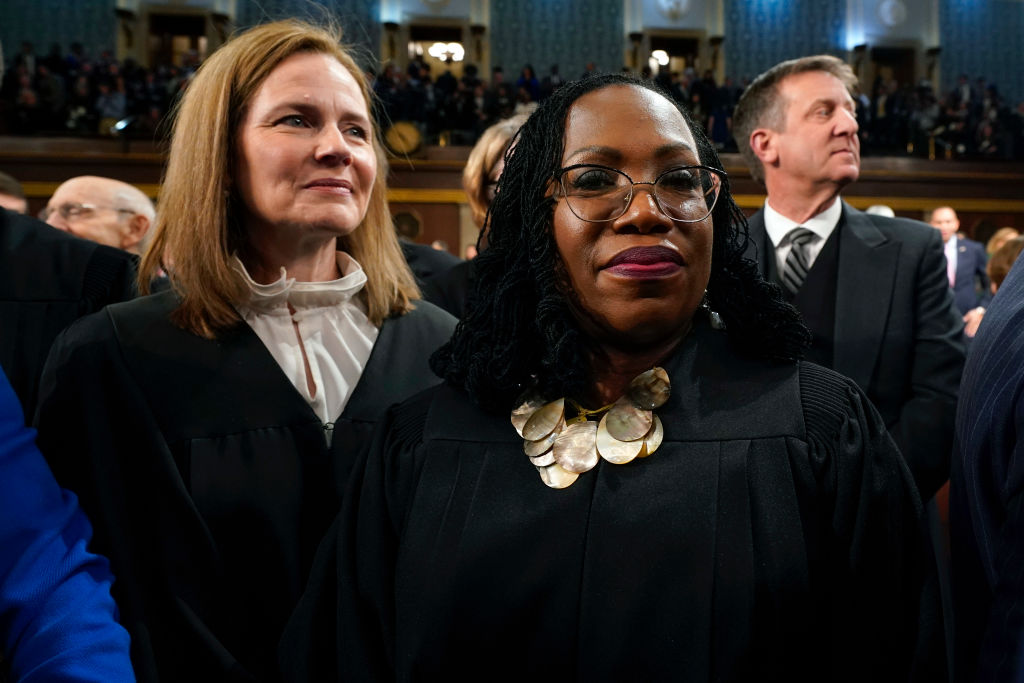

What does any of this have to do with the Roberts court decision in Students For Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College? More than I can say here. For one thing, I have not had time to fully read and digest the 237 pages of the decisions, the concurring opinions and the dissents. I know that didn’t stop President Biden from giving a ten-minute critique of the decision an hour or so after it was issued. He is plainly a faster reader than I, and someone who can cut to the heart of the matter. He later observed, “I think that some on the court are beginning to realize that their legitimacy is being questioned in ways that it hasn’t been questioned in the past.”

As it happened, I had two meetings scheduled today: one for the members of the National Association of Scholars (NAS), followed by a meeting of the NAS board. This bears mention because the central business of NAS has been opposition to racial preferences. NAS was founded in 1987 in part out of faculty resistance to the growing racial preoccupation of higher education. The 1996 successful referendum in California, Proposition 209, was drafted by two NAS members and championed by two others. It outlawed racial preferences in college admissions (and other contexts). The leader of the pro-Prop 209 coalition, Ward Connerly, is a member of my board, as is Gail Heriot, a member of the US Civil Rights Commission, who was also one of the key organizers of the 209 campaign. NAS has been involved in a substantial supporting role with every effort to overturn racial preferences and to unravel the diversity doctrine.

These matters have also been central to my professional life for some twenty-five years, from my book Diversity to my book, 1620: A Critical Response to the 1619 Project, with hundreds of speeches and articles in between. Which is to say: today was not just another day for NAS or for me. It was the culmination of decades of advocacy.

Still, I am reluctant to say what the decision really means. It will require not just careful reading but the time it takes for the subtle implications of the decision to work themselves out. Consider the five years between Powell’s enunciation of the diversity doctrine and the first time any university (it was the University of Pennsylvania) took it up in a serious way. There are, however, a few points that I would emphasize.

First, the decision explicitly rests on the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, not on the Civil Rights Act, any other legislation or any executive orders. That means it is constitutional law — and cannot be undone by Congress or overruled by a president who “strongly disagrees” with it.

Second, the higher education establishment long anticipated that the SFFA v. Harvard case might go this way — and it has been working tirelessly to undermine the spirit of it by putting in place workarounds that will allow it to continue to practice racial preferences in admissions. Some of these workarounds will be challenged and will be found illegal. That will take time — and will not stop colleges and universities from finding still other ways to thwart the court. My organization and its allies will vigilantly watch for these subterfuges and will do our best to defeat them.

Third, the diversity doctrine has been elevated to near sacred status among many college and university administrators as well as within the leadership class in much of American society. The allegiance of the true believers will not be broken by intelligent argument, hard evidence, or popular opinion, any more than it will by a Supreme Court decision. This is a deep matter of America’s culture war: indeed there is none deeper. Either we are a profoundly racist society that needs to be reordered top to bottom by those who possess the superior insight of “woke” radicalism, or we are a fair-minded republic founded on the principles of liberty and equality — and determined to treat one another according to our merits. The diversity doctrine was a wrong turn that took us nearly fifty years in the wrong direction, but we are proving once again that we can fix our mistakes.

Fourth, we can expect the next stage of the culture wars to be an all-out attack on the Supreme Court by those who find its current jurisprudence unbearable. That attack, of course, started before this decision but the decision itself is bound to become a focal point.

Fifth and last, the decision signals the need for new thinking about who we are as a nation. Racial division is a plaything of the left and also a toy for a much smaller faction on the right. Most Americans of all races want nothing to do with that division. But the culture is stuck on the “diversity” gear and we find it difficult to talk about our rich history, our heroic accomplishments and our place in the world as a beacon of liberty without slipping back into the facile conceit of diversity. We should thank the court for kicking the banana peel to the gutter. The Court has given us a gift in removing a moral hazard, but the Court can’t tell us what to do next. That is up to free people to make their own decisions.