Taipei

Nowhere is watching Russia’s faltering attempt to crush its democratic neighbor more closely than Taiwan. The Ukraine war is seen in Taipei as a demonstration of how determined resistance and the ability to rally a global alliance of supporters can frustrate a much larger and heavily armed rival. Taiwan has spent the past few years planning how it would cope if China attacked. It is developing a doctrine of defense warfare right out of the Ukrainian playbook.

China was carrying out military exercises off the east coast of the island last week when I met Joseph Wu, Taiwan’s foreign minister. “They keep circling in that area,” Wu says. “Nonstop for two weeks, and it is very threatening.” There were also reports of China carrying out missile training exercises in its remote northwest, simulating attacks on a Taiwan naval base. “We are on the front line against authoritarianism,” he adds. “The reaction to Ukraine here is very strong because it is a mirror image of what might happen to Taiwan in the future.”

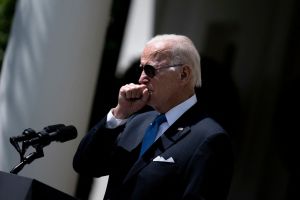

Joe Biden makes the same argument. The theme of his five-day trip to Asia this week was that world affairs are being redrawn and the dividing line is not Russia vs the West but “autocracy vs democracy.” When asked, the president said that America would defend Taiwan — a break from the official policy of strategic ambiguity.

No democratic country is more aware of Taiwan’s role in the “front line against authoritarianism” than Japan, whose Senkaku Islands are much closer to Taiwan than the Japanese mainland. The islands are also claimed by China and would become essentially indefensible if Taiwan fell. Fumio Kishida, Japan’s new prime minister, has slapped sanctions on Russia and joined Germany in pledging to double his country’s defense spending. Kishida was in London earlier this month, talking with Boris Johnson about a Japan-UK defense pact.

Such talk is intended to make Xi Jinping pause for thought in his plans for China’s reunification with Taiwan. One reason the western alliance is equipping Ukraine with hi-tech anti-ship missiles, used to great effect against the Black Sea Fleet, is to demonstrate to Beijing that any amphibious assault comes with huge risks. But Xi can also learn from Vladimir Putin’s mistakes. “We might have a breathing space,” Wu says. “But they are learning [from Ukraine] so they can improve their military activities, and if they think they have overcome the difficulties of the Russian military, they might be tempted to use force.”

Ukraine’s resistance — and the speed with which ordinary citizens turned into guerrilla fighters using portable Javelin and Stinger missiles — has reinforced faith in what Taiwan calls its “porcupine strategy.” This plan predates the Ukraine invasion and is credited to Admiral Lee Hsi-min, who headed the island’s armed forces between 2017 and 2019. He argued that Taiwan could not fend off China in traditional warfare (Taiwan’s defense budget is $17 billion this year, while Beijing’s is an estimated $288 billion), so should not waste money on a large defense force. Taiwan had to be smarter.

Among the small, lethal and mobile systems that Admiral Lee pushed for were fleets of mini assault boats, equipped with anti-ship missiles and based in small fishing ports. They’re easily hidden and immune from long-range missile attacks. “You should redefine winning of the war,” Admiral Lee says. “Don’t try to destroy the enemy totally in the battlefield. You just need to ensure the enemy fails to accomplish their mission. You need to be robust, make your enemies believe it is impossible to take over Taiwan. Then you are safe.”

A Chinese invasion would probably begin with a blockade or the seizure of small Taiwanese-controlled islands closer to China. But much like Putin’s original plan for Ukraine, an invasion would rely on overwhelming force. Estimates vary, but it would require up to two million combat troops, along with thousands of tanks, artillery pieces, rocket launchers and armored personnel carriers. All of these would need to cross the Taiwan Strait in a fleet that would include thousands of requisitioned ferries. Preparations would be impossible to hide.

Might China’s army run into the same problems as Russia’s? Taiwanese strategists see parallels and opportunities. “The Taiwan Strait is actually the highway for the Chinese army, where they are most vulnerable,” according to Su Tzu-yun, a research fellow at the Institute for National Defense and Security Research in Taipei, a military-linked research group. Taiwan’s coastal terrain is a defender’s dream: only fourteen of its beaches are regarded as suitable for an amphibious landing. Most of the east coast is made up of cliffs, while beaches on the west coast are lined with densely populated towns, mud flats, paddies or other coastal ponds. It could be designed to slow down an enemy advance.

So the challenge for an invader is far greater than Russia’s land invasion and, despite recent years of rapid modernization, the People’s Liberation Army is still notably poor at “joint operations.” Just a few weeks ago, the state-owned newspaper PLA Daily admitted that China needs more military leaders capable of thinking across the traditional navy, air and land divides.

Then there are the treacherous waters and winds of the Taiwan Strait, known locally as heishuigou or the “Black Ditch,” which mean there are only two realistic windows for an invasion every year: late March to the end of April, or late September to the end of October. Taiwan’s elaborate defenses against attack from the sea include forests of steel spikes, layers of sea mines (to protect the approaches to the vulnerable beaches) and “seawalls of fire,” an underwater system of pipelines to release gas and oil ahead of advancing invasion forces. They would be ignited by gunfire.

Taiwan’s democracy itself is seen in Taipei as one of its most important defensive assets. The island, which was a military dictatorship until the 1990s, is one of the world’s most successful new democracies, so it can claim to be on the right side of Biden’s “democracy vs autocracy” divide. A Chinese invasion would be seen by the West as an assault on the principles of liberal democracy and self-determination. Since 90 percent of the world’s top-end microchips are made in Taiwan, the island’s role in the global economy is also crucial. There is a joke in Taipei that if Chinese missiles started falling, the best place to shelter would be in microchip factories, because they are so vital they can’t possibly be targeted.

The US is Taiwan’s principal arms supplier. But Biden’s verbal assurance that he would defend Taiwan is not something the Taiwanese will depend upon. “We want to show the international community that we are willing and we are determined to defend ourselves,” says foreign minister Wu. As Admiral Lee put it: “The only thing you can rely on is yourself.”

Wu says he was personally surprised by western unity and resolve over Ukraine — and believes it probably came as a shock to Beijing too. “This is good for Taiwan in the sense that if China wants to attack Taiwan, we hope the democracies can also unite together in reacting to the Chinese aggression.” Biden now talks as if the future of the US-led (or “rules-based”) world order is on the line in Taiwan. If the island fell to China, that would signify the end of the long American century. China would be the dominant power in the world’s fastest-growing and most strategically important region. America’s regional allies — Japan and South Korea — would have little choice but to reach an accommodation with Beijing.

The Ukraine war is almost obsessively covered in the Taiwanese media. Wang Jui-ti, a thirty-five-year-old Taiwanese citizen, became an instant celebrity when he signed up for Ukraine’s foreign legion, the International Legion of Territorial Defense of Ukraine, and began posting from the front line. “I want to do my part to defend basic human values,” he said.

There has been much coverage of the bravery and will to resist shown by young Ukrainians, which seems to have affected young Taiwanese. Polls conducted after the start of the war show a sharp increase in the number of people willing to fight for their country in the event of a Chinese invasion — 70 percent say they would take up arms. This has, in turn, encouraged government plans to revamp the island’s territorial defense forces. Ukraine has shown the world what a determined citizenry can do.

In many ways Taiwan is already at war: a gray war. As well as routine military intimidation, Taiwan faces constant cyberattacks, many of which target its hi-tech companies. It is also the most targeted country for spreading false information, according to the Sweden-based V-Dem Institute.

The official charged with countering this is digital minister Audrey Tang, who has devised a defense called “humor over rumor.” It works closely with comedians to rapidly respond to Chinese disinformation with a joke or a meme, and a short factual repudiation. “The idea, very simply put, is to make the clarification even more viral than the conspiracy theories,” said Tang (who is also Taiwan’s first openly transgender minister).

China’s gray warfare had for many Taiwanese become almost background noise, something they had learned to live with. Russia’s aggression has been a wake-up call. “We should thank Ukraine. It’s good for Taiwan,” an elderly taxi driver said to me as I headed back to the airport. Then he asked if I thought China would still invade. It was a question I heard many times in Taipei. Thanks to Ukraine, the Taiwanese realize they can’t afford to wait for an answer.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.