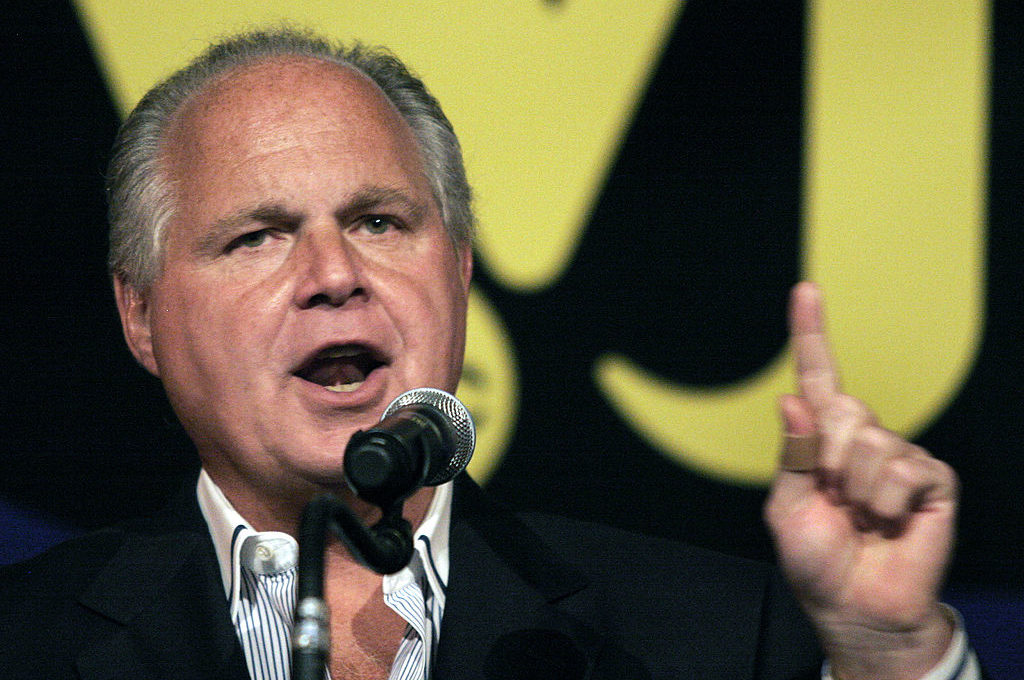

‘The cutting edge of societal evolution.’ That was one of Rush Limbaugh’s catchphrases in the 1990s, and it was an apt description of a man who revolutionized radio and politics alike. Limbaugh has now died at age 70, but the societal evolution that he accelerated continues. This is why Limbaugh will still be loved by the right and hated by the left for years to come.

Rush was a media powerhouse in his own right as a radio host, but he was also the grandfather of Fox News. Ever since the Nixon years conservatives had thought that there could be a mass audience for their message, one large enough to support a television network. Efforts to create one, or buy one of the existing networks, all fell flat, however. There was an established market for the conservative intellectual gadfly, a William F. Buckley Jr or a George Will or, from the libertarian wing, a Milton Friedman. Men like these had syndicated columns and space in magazines like Newsweek. Buckley’s Firing Line was a PBS success. The McLaughlin Group, along with Robert Novak and Pat Buchanan as mainstays of the early CNN, showed that conservative commentary could thoroughly reinvigorate the old political chat-show formats, where reporters kvetched with one another and guests from the world of officialdom about the day’s news. But these all served as conservative contrarians within liberal institutions. Buckley had an institution of his own, National Review, but NR didn’t reach millions the way television, radio and the major newspapers and magazines did.

Conservatives had enjoyed a degree of success with talk radio before Rush Limbaugh. Not only did broadcasters like Clarence Manion have large audiences, they also exerted some pull on Republican politics as well, particularly in raising support for Barry Goldwater. But figures like Manion (who died in 1979) had largely vanished by the time a new style of conservatism came to power with Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. Reagan was born in 1911, but his Hollywood background and natural gifts as a communicator (and humorist) helped to change the conservative sensibility. He wasn’t alone in this: journalists like P.J. O’Rourke and political activists who found new ways to mock and satirize the left in the years after Watergate were part of this change, too. The paradox of the Sixties — and the Seventies, too — was that in stirring up a spirit of rebellion and questioning of authority, the cultural radicals did more damage to the old liberal pieties than they did to the right, which had been critical of everything ‘establishment’ since at least the New Deal. Today when po-faced progressives lament the unruliness of the American right, with its mocking memes and crazed conspiracy theories, they fail to recognize that the right has only been more successful in using weapons that the left forged in the first place.

That’s what Rush Limbaugh did. Radio was the medium of rock and roll and all the rebellion it entailed. Limbaugh brought a rock irreverence to conservative commentary, and won an audience — perhaps, like the rock audience, mostly an audience of baby boomers — in the millions. Limbaugh didn’t need a platform like the Washington Post or Newsweek or CNN, his show ultimately became its own platform, one entirely oriented toward right-leaning consumers. (To be sure, this platform itself depended on the radio networks that carried it, though Limbaugh became a hot enough star to set the terms he wanted.) Promoted by Limbaugh, the irreverent style carried over to electoral politics and helped fuel the Republican takeover of Congress in 1994, after some 40 years of Democratic dominance in the House of Representatives. Roger Ailes worked with Limbaugh on a television show, which wasn’t a success, but Ailes applied something of the Rush method to Fox News, whose business model arguably owed as much to Limbaugh as it did to a cable news forerunner like CNN.

Like Fox, Limbaugh usually didn’t stray far from the line set by Republican presidents. Limbaugh was a defender of the George W. Bush agenda in the days of the Bush presidency, and he became a Trump Republican in the Trump era. Limbaugh wanted an omnibus conservatism, and he took little note of sectarian intellectual squabbles on the right — squabbles which, as it happens, can be matters of life and death, war and peace. But in this he was like most of his listeners and perhaps most Republican elected officials (though obviously not all). Toward the end of his life, Limbaugh seemed to become more ‘paleo’, even beyond the effect that Trump may have had on him. This might also reflect the interests of a younger generation of producers and staff — the new spirit of rebellion on the right finds neoconservatism tepid and staid, a thing to be mocked the way Limbaugh mocked establishment liberalism.

Limbaugh’s career testified to the enduring connection between communications media and politics in our republican system. The period before Limbaugh rose to prominence was a lot like conditions today, and the great ambition of liberals and progressives is to take us back to the era of the Fairness Doctrine, which was not about fairness at all, but about quarantining conservatism. The Fairness Doctrine applied to the biggest media of the time — radio and television, both broadcast over the public airwaves — and gave conservatives only a token presence, which had to be equalized by time for a liberal spokesperson. (That, at least, was how programming directors typically interpreted this vague federal regulation.) The doctrine did not address the overall slant of radio and television news, which then, as now, was toward the establishment left. Nor did the Fairness Doctrine help to balance out the leftward lean of most of the nation’s biggest newspapers, which then, as now, gave conservatives only a token presence on the op-ed pages. Until Limbaugh invented a new medium — a new mix of an old medium and new style — conservatives were in effect prisoners of liberal institutions, with only as much speech as liberals allowed them.

What the Fairness Doctrine and liberal dominance of old media accomplished before the 1980s, liberals hope to achieve again through the power of the social networks today. Rush Limbaugh couldn’t exist under the Fairness Doctrine (of which even figures like Manion fell afoul), and soon — if not already — a new Limbaugh won’t be able to exist under the political controls imposed by YouTube and Twitter. Precisely at the point a Limbaugh begins to take off, by irreverently satirizing the pieties of progressives, is when his speech will be squelched. Only gadflies and ‘conservatives’ who ultimately agree with liberals will be tolerated, because only their speech is safe. Popular conservatism is a threat to the moral and political order.

The trouble for progressive liberals, as Limbaugh demonstrated, is that millions of Americans don’t accept the orthodoxy that the old media and now the new social networks promote. They want to debate the moral and political order, the way free citizens should. To do that they need a platform, and if they’re deprived of one by government or big business, they’ll look for another, no matter how irreverent it might be. Rush Limbaugh was outrageous enough to smash through the barriers liberals had built. If liberals are worried about another Limbaugh being even more shocking to their sensibilities, they should do the opposite of what their instincts tell them: give up control, and encourage more speech, not less.